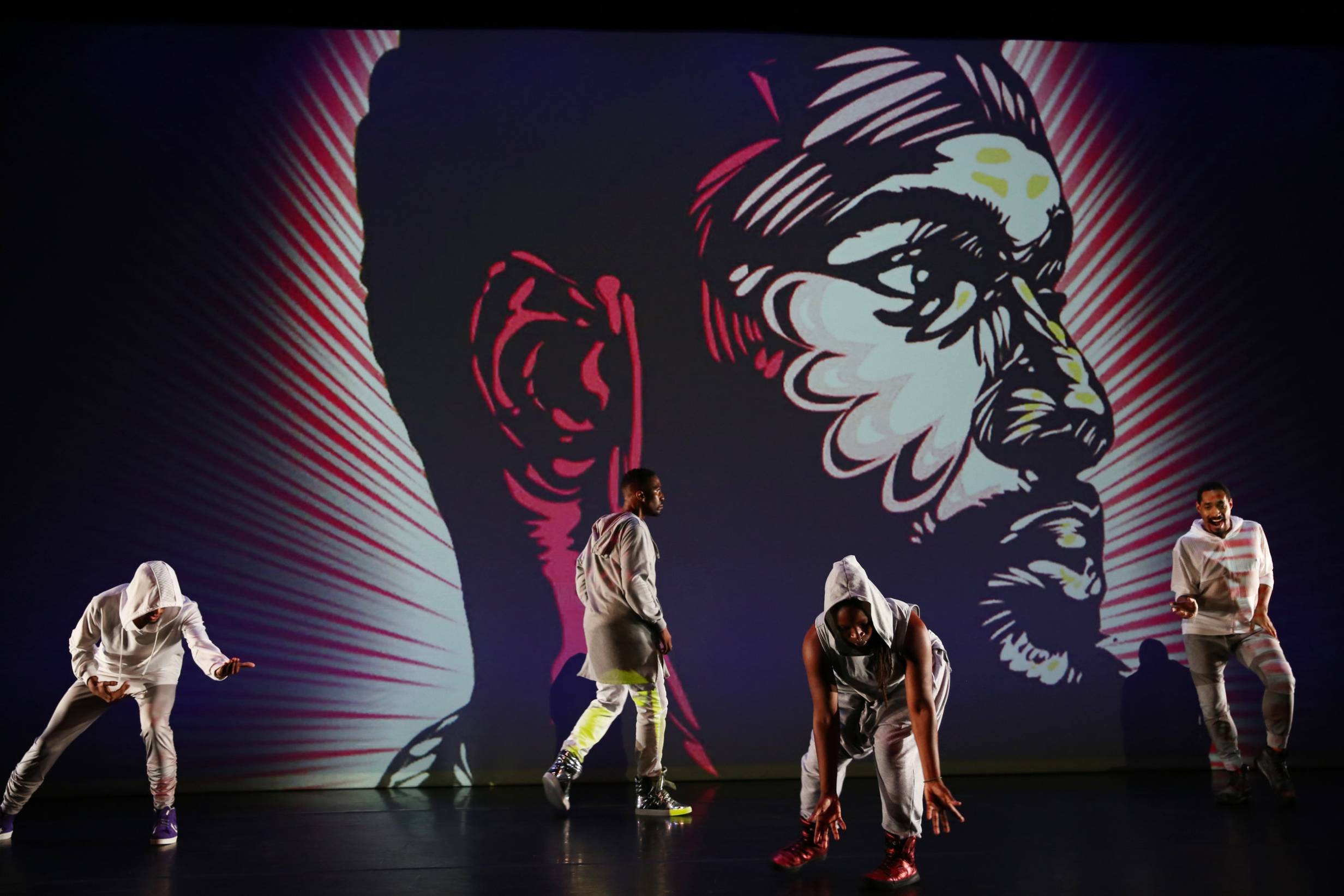

Virago-Man Dem is Bessie Award-winning choreographer Cynthia Oliver’s newest work. Oliver is a professor of dance and Associate Vice Chancellor for Research for the Humanities, Arts, and Related Fields at the University of Illinois. Virago-Man Dem is an evening-length dance-theater work utilizing original music from composer Jason Finkelman, visual design by John Jennings and Stacey Robinson of Black Kirby, projections by John Boesche, costume design by Susan Becker, and lighting design by Amanda Ringger.

Born in the Bronx and raised in the Virgin Islands, Oliver’s process for creating this work engages with the personal experiences of Caribbean and African American men and male-identified folk, offering a nuanced, expressive, and expansive view of black masculinity. Oliver creates a safe space for performers Duane Cyrus, Jonathan Gonzalez, Ni’Ja Whitson, and Niall Noel Jones to be vulnerable on stage revealing “more possibility, more understanding of the complexities of black life, more tenderness, humanity, love.”

Smile Politely: In a press release of your world premiere of Virago-Man Dem at the Next Wave Festival, “the Latin prefix “vir” means “man” the suffix “-ago” indicates female… [Virago-Man Dem] celebrates black masculinities in their infinite variety and nuance.” Could you speak more about the meaning of the title, and why you wanted to explore the nuances of black masculinities?

Cynthia Oliver: In the Anglophone Caribbean, virago has been deployed as something derogatory to charge at a woman who does not behave in a conventional femme manner. As a woman who does not always display conventional female behaviors — I’m bold, I’m brash, I’m forthright sometimes — I chose to play with that term to represent myself in a work that investigates the worlds of men or masculinity. I say masculinity as distinct from men. I started this project thinking that this would be a work about people born male and over time I extended the work to include people who identify with masculinity, whether they are born male or not.

There’s a rampant misconception about masculinities in the Caribbean, that the Caribbean is a rigid and homophobic place. There is an element of homophobia there, a significant element, but there are also very flexible, broad and expansive ways of performing masculinity there that are not necessarily recognized here in the continental US. That fluidity exists within our communities, but we don’t get to see that in the media. In black communities all over the United States there are comprehensive ways that black men behave: funny, tender, compassionate, etc. I know that those characteristics are in my own community, my own family, so I was interested in reflecting that. Especially at a time in the country when it seems like there’s a target on a black man’s back. That’s why I wanted to make this piece.

Smile Politely: What was the process for creating Virago-Man Dem?

Oliver: We started the process in Trinidad in July of 2015. I was there on a fellowship at New Waves Institute, and New Waves Institute was collaborating with Dancing While Black, an organization in New York created by a fellow Caribbean person. As an artist, they offered me space and people to work with. I had state-side dancers, local Trinidadian dancers, and then I had a couple of community folks who were interested in dance but weren’t dance professionals all in the room together. We’d start with a conversation. I asked everyone in the room, what was their epiphanic moment? What was the moment when they realized they were different because of their sex? Because of their gender? When they were told how they were supposed to behave or were disciplined because of something they had done? Every person in the room had that moment. So, we talked about what disciplining their bodies meant. Then we started building a physical vocabulary.

I was particularly interested in taboos. If people were told that they couldn’t move a certain way because they were a boy, those were the movements that I wanted to find and engage. But, we also explored movements that were sanctioned. I incorporated moments of a stereotypical kind of gate, then I would depart from that. That process gave me the template that I then took to each residency after that. I always made sure that I was engaging with the community. I wanted to hold myself accountable, I wanted people to be able to connect with the performance, so I made sure that I connected with and spoke to male identified people, that they saw the work as we were building it, that they responded and had conversations with us.

Smile Politely: So, you were interested in the performers exploring the performance of masculinity and you wanted to stay true to their experience in the final choreography?

Oliver: Yes. Their experience, my experience of black masculinity, my contemporary experience as well as a nostalgic one, were all living in the room at the same time. I was interested in all of us negotiating that.

Smile Politely: There are a lot of collaborators on this performance, “original music from composer Jason Finkelman, visual design by John Jennings and Stacey Robinson of Black Kirby, projections by John Boesche, costume design by Susan Becker, and lighting design by Amanda Ringger.” Did you engage a similar creative process with your interdisciplinary collaborators as you did with the dancers?

Oliver: Well, the two visual artists that are part of Black Kirby, John Jennings and Stacey Robinson, yes, because we’re both looking into what is possible for a black future for men, for masculinity. John Boesche, who became a part of the project to do the animation, is not a black man but is really attuned to what we are trying to do in the piece. He would ask questions about where we were trying to go and what the propositions were. My costume designer, Susan Becker, is a white woman and she is acutely aware of the gap between her experience and the experience that I was going for in the piece. She is a brilliant designer, came in with a series of questions, watched the piece, and we’d have conversations. She watched the performers be themselves. They are already stylish individuals, so she looked at their personal style, incorporated a lot of elements of who the people inhabiting the piece already were and tried to amplify that.

Smile Politely: Why did you decide to use projection and animation in Virago-Man Dem?

Oliver: I saw John’s and Stacey’s work and I was fascinated by the aspirational nature of it. An engaged way of thinking about the imagination helps black people in general and black men in particular negotiate their very real existence. Our imagination is a part of the prescription for survival. I wanted that to be part of the work.

John came in the studio at one point and did some free drawings while we were rehearsing. Those appear in the projection as abstract articulations of the movement, which for me relates to a kind of spirit sense in the work.

Smile Politely: What do you mean by spirit sense?

Oliver: That thing that is undefinable, that lives in excess but through the body, that power we call on, that we rely on, to carry us through no matter the conditions that we find ourselves in. There’s the image of the masculine, then there are abstract images that are articulations of something that exceeds it. Towards the end, the abstract, excessive image appears again as something more recognizable. Then we see the performers appear on screen as cyborgs.

Smile Politely: Why do they transform into cyborgs?

Oliver: Because the black body is always already excessive. How can we imagine black masculinity surviving or moving into the future but by imagining it as the extension of the human beyond the flesh?

My research has always addressed black cultural practice that exists in excess of what folks might think is obvious. For example, my dissertation was about the pageantry of black womanhood in the Caribbean around notions of nation. Pageants can appear to be frivolous nonsense that women engage in, but if one looks historically at what black womanhood can do, we see that pageantry was a vehicle for speaking truth to power, for establishing a working class and then a middle class, for informing your community of current events, for establishing certain cultural and behavioral codes. Those might be considered some of the positive things, there are also negative things that it produced. My research looks beyond the surface of a cultural production for its more far-reaching effects and usefulness. What Black Kirby is doing is similar in a visual context, so that’s part of the reason why we jive so well. We’re taking a step back from our own cultural production and examining that within a cosmology that might not have been as readily acknowledged through conventional American means.

Smile Politely: You wrote in your bio that choreography and text is intricately intertwined in your work, one cannot exist without the other. Did you use text for this piece?

Oliver: I did!

Smile Politely: How did you generate the text?

Oliver: I wanted vulnerability, I wanted real, I wanted material that spoke from the heart and the gut. I wanted text that would elicit a kind of memory, that would make the audience think about their own epiphanic moments as they heard the performers speak. For that, I depend on the performers and their experience, on their willingness to retell and reveal those experiences. That’s where it comes from.

Smile Politely: Why are you interested in the vulnerability of the performers?

Oliver: So much of what we see around masculinity in contemporary culture is a mask. I’m not interested in reproducing the mask, I’m interested in the person that’s behind it, the person who must negotiate their own mask, or refuses to negotiate that, or decides at certain times to negotiate it. I don’t need what I see every day in American culture reflected back to me. I see it enough. I need something else, I want something else, and I want something else for you. The whole reason for making the piece is that I wanted to offer the world something else. That’s why I required the performers to bring something else, an opportunity to really be vulnerable. Of course, that means that we need to create a safe space for that to happen and I work very hard at that. I worked with most of these folks for three years. So, it has taken time.

Smile Politely: Do you feel that this work has an impact for the C-U community?

Oliver: The C-U community has been a part of the process. This is a place where I had small, all black male groups look at sections of the piece and talk with us about it. That was special. So yes, I hope that the community here feels a special connection to it. We have our own issues here with young men and I hope this offers something to that conversation.

I’ve spent most of my career looking at and talking about performing aspects of women’s worlds that I find intriguing. But while doing that, if you separate one gender out of course you’re going to notice what’s happening with the other. As the mother of a young man I wanted to tackle the other gender at least once and I feel like this is that project for me. Hopefully it is something that is meaningful to both my child and my larger community.

Virago-Man Dem

Krannert Center for the Performing Arts

500 S Goodwin Ave

Urbana

Thursday, November 15th at 7:30 p.m.

Photos: Virago-Man Dem at Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival, October 2017