If you wanted to create a feature-length animated film and overlay it with some music from a long-dead 1920s jazz singer that no one has ever heard of, you might think there would be a straightforward path for doing so legally. Unfortunately, you would be very, very wrong.

If you wanted to create a feature-length animated film and overlay it with some music from a long-dead 1920s jazz singer that no one has ever heard of, you might think there would be a straightforward path for doing so legally. Unfortunately, you would be very, very wrong.

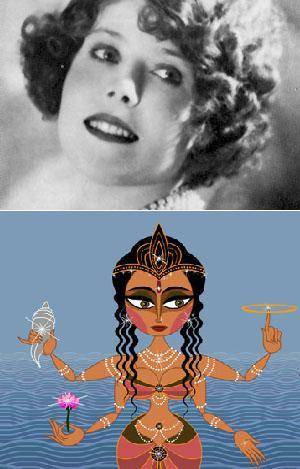

Urbana native Nina Paley has learned that part of the job of being an independent animator is to understand the fine print of American copyright law. Her attempts to distribute her film Sita Sings the Blues has caused her all kinds of headaches, because the songs of 1920s singer Annette Hanshaw are integral to the telling of her story. To get an idea of the scope of the problem, see Nina’s handy chart over at www.sitasingstheblues.com of who owns what and who needs to pay who, should you be so adventurous as to show the film to anyone.

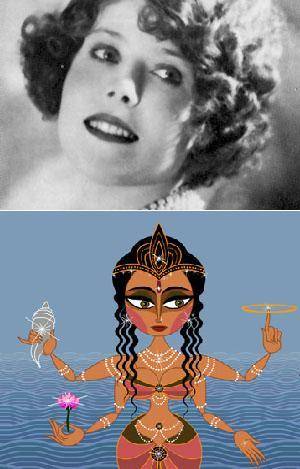

Sita Sings the Blues is a retelling of the Indian epic Ramayana. It will be featured at Ebertfest in two short weeks, where Paley will be on-hand at the Virginia Theater to discuss it. A couple of weeks ago, we talked to Paley about growing up in Urbana and the film itself. We caught up with her recently to ask about her copyright problems.

Smile Politely: If the Annette Hanshaw recordings are causing such headaches, why not remove them?

Nina Paley: The songs themselves inspired the film. There would be no film without those songs. Until I heard them, the Ramayana was just another ancient Indian epic to me. I was feebly connecting this ancient epic to my own experiences in 2002. But the Hanshaw songs were a revelation: Sita’s story has been told a million times, not just in India, not just through the Ramayana, but also through American Blues. Hers is a story so primal, so basic to human experience, it has been told by people who never heard of the Ramayana. The Hanshaw songs deal with exactly the same themes as the epic; but they emerged completely independent of it. Their sound is distinctively 1920s American, and therein lies their power: the listener/viewer knows I didn’t make them up. They are authentic. They are historical evidence supporting the film’s central point: the story of the Ramayana transcends time, place and culture.

SP: Can you untangle the copyright issues for us?

NP: There are issues with the recordings and there are also issues with the compositions that underly the recordings. The copyrights on the recordings were not renewed, which means they are not protected by federal copyright law. However, they may be protected by New York State law, which means it might be illegal to release the film in New York state.

Then there’s the question of whether the New York state law applies out of New York. However, the recordings are completely free and legal outside the U.S. It’s not clear inside the US whether the problem is just New York or the whole U.S., but no U.S. label would want to release something that they couldn’t sell in New York state.

Most people don’t know about this, and the result of this law is that it is legal to share American culture outside the U.S. Everyone has access to American culture except Americans.

So, it’s a big convoluted mess. I could be sued for it to be shown at film festivals in New York state. We’ll have to wait and see.

SP: And that’s just the songs, not the compositions?

NP: The copyrights on the compositions were renewed, and these songs are traded from corporation to corporation, so whoever initially owned them, sold them, and they’ve been sold again and again, and now they are mostly controlled by giant multi-national media conglomerates like Warner, Sony and EMI. The licenses you need for them are different in different countries.

SP: So how much would it cost to clear them?

NP: What they initially quoted me was an average of $20,000 per song. There are 11 songs in the movie, so it would require $220,000, which was more than it cost to make the film.

Since then, they have very generously, from their point of view, brought it down to a mere $50,000, but there are all these strings attached, so I’m not able to fully clear the songs.

The problem is that because I’m giving it away for free, they might say say, “Oh, you sold those, you just sold them for zero dollars.” Whereas I would say they are promotional copies, and only a lawsuit would tell. So, it’s in their hands; they could totally sue me.

SP: Can’t you negotiate a special deal, since this is so small-scale compared to a distributed release?

NP: There was no way to negotiate their contract, because it would have cost them more to negotiate than they would have gotten from me. The contract is $3,500 per song, and it would have cost them more than $3,500 for their lawyers to revisit the contract and modify it.

I must emphasize this is a system problem. This is not an individual’s problem. Everyone involved in this is truly just doing their job. It’s the system itself that is broken. If you can’t negotiate the contracts because it costs more money to negotiate a reasonable deal than they could earn, it is crazy.

I borrowed $50,000 to decriminalize the film, just to make it a little bit safer to give the film away for free, which is crazy.

SP: Why would corporations hang onto all these old copyrights if they are going to make it so hard to use them?

NP: Well, there’s a good answer to that. The corporations that hold these copyrights are media companies that also control most of the new media that comes out. Estimates vary, but it’s said that 98 percent of all culture is unavailable right now because of copyrights. So the reason they hold the copyrights isn’t because they want to get paid, it’s because they don’t want all the old stuff competing with the media stream that they control now.

If you control Britney Spears, people are only going to listen to Britney Spears if they can’t listen to anything else. That’s why I think the system is still in place.

SP: That would certainly explain the success of Britney Spears.

NP: There’s so much old good music that people would be listening to now. But if people listened to it, what would they do with the new stuff? If culture were freer, it would compete with people’s time in consuming new stuff. That’s my theory, anyway.

I don’t think any of this is conscious, or that it’s a conspiracy theory. All these rules were developed before we had the internet. The times are just changing so fast, business law isn’t coping very well.

SP: You must be tired of dealing with all this.

NP: The film has kept me really busy, even though all I want to do is let go of it. But the more I let go of it, it seems the more I have to do.

Sita Sings the Blues is now available for free viewing over the internet via a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License. DVDs will soon be available for purchase at http://www.sitasingstheblues.com/store.html. You can also just donate money to Nina, and hardly any of the money will go to big corporations.