Saturday morning of Pygmalion is, historically, a difficult time for all participants. Friday night extends quite late, and by my rules, “It’s not tomorrow until I go to sleep,” which makes noon feel like 6 a.m. Still, the sadists at PygLit have slated some of the most intriguing writers at the goddamn crack of noon. I guess they’re taking after the tradition of Parasol Music shows, which previously have been the only thing that could motivate me to rouse and find a six-shot (of espresso). Still, these authors will only be reading for 30 minutes, so set the alarm for 11, rustle up some Flying Machine or Columbia Street Pygmalion Blend, and get over to the Accord for a set of weird, touching, and weirdly touching stories read by local and national authors.

JAMES TADD ADCOX

Many of us have read Ray Bradbury’s famous 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451, a dystopian novel set in a future American society where books are illegal, and “firemen” burn any books that are found. While the James Tadd Adcox dystopian novel Does Not Love does not include burning books, it similarly raises important questions about what we are and are not allowed to know, and how we view our relationship with our government, ourselves, and those closest to us.

Meghan McCoy sat down to speak with Mr. Adcox about Does Not Love, and to discuss when living in a society that surveils and controls its citizens, how do you know when you, or what you believe, is the opposite of what is allowed? And more importantly, can you push back against it?

Smile Politely: Does Not Love follows the marriage of Robert and Viola after the stillborn birth of their child in Indianapolis. During this time, Robert and Viola’s life is overshadowed by the FBI, as they are seen as potentially dangerous and Viola is being investigated because her “sadness runs counter to our way of life” (139). When you were writing Does Not Love, why did you choose to depict sadness, or depression, as dangerous? How does emotion, or the lack of it, play into the construction of Viola and Robert’s characters?

James Tadd Adcox: Sadness is dangerous, I think, or it can be. But it also has the potential to act as a creative force. Sad people aren’t content. Sad people want things to be different, even if they’re not sure how. The fundamental command of the totalitarian state, according to — Zizek? Lacan? …somebody — is: be happy. Not that I think we’re living in a totalitarian state. I mean, give us a couple of months, let’s see how things shake out.

SP: In Does Not Love, obedience and control play a central role in the conflict between the overarching FBI, pharmaceutical companies, and the general population. How does the break of control and obedience in society also relate to the breakdown of Robert and Viola’s own marriage, and her strong interest in BDSM? What is the significance of the relationship between Viola and the FBI agent who admits to spying on her because she’s a threat to national security?

Adcox: I think our interest in things — non-standard sex or beekeeping or whatever else — tends to be overdetermined. Some of Viola’s drive towards her affair is a response to grief, but not all of it. I didn’t want to make it a simple causal relationship, x leading to y. Some of her desire is just there, inexplicable and irreducible. It was important to me that she and Robert both have that sense of agency.

I started the novel during the Bush years, when it felt impossible to write about a librarian (like Viola) without thinking about the way the government was making libraries into points of surveillance, and the ways that librarians were resisting this. The FBI agent is sort of the “Iago” of the novel, as in the villain from Othello. Not so much the destabilizing force as the thing that brings certain dormant instabilities, in Robert and Viola’s life and in the world around them, to the surface.

SP: Throughout the novel, love and emptiness are often closely related, with emptiness at one point described as “the space that consumes all of our efforts to fix things, to make them right” (111). What do you think is the importance of space, or the space of emptiness, in the lives of the characters? How does love, both individual and marital, widen and fill that void?

Adcox: Desire is probably more central to this book than love. I don’t know that either of my protagonists actually loves the other. They care for each other—this isn’t meant to be an especially cynical book, and I think that element of care that they have for each other is important. But they are driven less by love and more by desire—for a certain kind of life or to escape a certain kind of life. I think Viola probably recognizes this more than Robert, which is part of why her desire is less focused and conventional than his, more diffuse.

As for emptiness: desire is a certain shape, a form. And there’s an emptiness at the center of it, I think. “Desire is always desire for itself” is another of the slogans I had in mind while writing this book.

Which doesn’t make desire bad, incidentally. I’m a formalist. I like form. I have a certain love of emptiness.

SP: Does Not Love ends on a surprisingly optimistic note, despite the many challenges Robert and Viola face. Why did you decide to end the novel that way, particularly since it’s dystopian fiction?

Adcox: I guess I thought of it as semi-optimistic. Certain things are terrible, certain things are covered up and/or conveniently ignored, but the world doesn’t end. All of our movies about the apocalypse have a great sense of closure, I think, but I doubt that’s how it happens. People keep living until they don’t.

SP: What are some of the main points you hope to convey to your readers, both within Does Not Love and your other writings? Is there anything you hope to encourage your readers to consider about the current world though the alternate reality in Does Not Love?

Adcox: The “alternate reality” tag was part of the synopsis put together by the publisher. Which, of course, I agreed to — overall I thought it was a really good synopsis, and I had already tried (and failed) to come up with a good summary of the book on my own. But I always considered the Indianapolis I was writing about to be the strange place as it exists: a town created by committee, placed in the geographical center of a state, originally a single perfect square mile. The fact that that square mile in the center of the state happened to be on top of a swamp and near no major waterway didn’t faze the town’s founders a bit. You could say that the town was created as sort of formal exercise, and carries a certain emptiness at its heart. As I mentioned above, I don’t see that as altogether a bad thing.

On the other hand, anyone writing fiction is engaged in creating alternate realities. There’s no sense in just repeating the world back to itself, I don’t think.

—

James Tadd Adcox is the author of a novel, Does Not Love, and a collection of stories, The Map of the System of Human Knowledge. A novella, Repetition, is forthcoming October from Cobalt Press. You can learn more about him and his writings through his blog.

– Meghan McCoy

MARYSE MEIJER

A woman’s fantasies about her lover being sexually assaulted in prison take that lover to increasingly uncomfortable places. A man stubbornly persists in loving a feral child he found despite her alarming ferocity. A woman attending a weight loss camp finds release from more than one of her frustrations with a local fox. A man enjoys an intense erotic and romantic relationship with the forest fire he started.

These are just some of the situations found in Maryse Meijer’s envelope-pushing debut collection Heartbreaker, a gleeful exploration of instances of human love and sexual desire well beyond the boundaries of the expected. Reviews of Meijer’s work often use adjectives like “dark”, “disturbing”, and “edgy.” Smile Politely chatted with Meijer over e-mail about what Pygmalion attendees can expect from her reading on Saturday.

Smile Politely: Heartbreaker is a little difficult to describe to people—your stories explore what is often somewhat grim terrain, but you seem to have real affection for your characters and there are a lot of moments of dark humor along the way. Is Heartbreaker typical of your long-term writing interests, and if so, what do you think the appeal is for you in visiting the more shadowy regions of the human heart?

Meijer: I’m interested in people’s secrets, and the best secrets, for me, are usually about desire, and what we’re willing to do in service to our own desires or the desires of the people we love. And violence is all mixed up in that, whether it’s self-directed or otherwise…I think romance is inherently violent. It’s an extreme and it drives us to extremes. So I’m interested, partly, in seeing how that plays out across a whole spectrum of situations, personalities, permutations…we’re a culture that’s obsessed with romance and sex, and we don’t often think about how the desire to connect with other people on those levels might make us lonelier, more desperate, even degraded. I’m trying to take the romance out of romance, the sex out of sex, while at the same time trying to find the moments where it is all human and humorous, beautiful and true.

SP: A lot of these stories deal with taboo subjects and are pretty intense. It seems like hearing them read aloud in a large group setting like Pygmalion would heighten the reader’s awareness of that “forbidden” content in interesting ways. Have you noticed any differences in how readers respond to your work based on whether they first encounter it through a live reading or on the printed page?

SP: A lot of these stories deal with taboo subjects and are pretty intense. It seems like hearing them read aloud in a large group setting like Pygmalion would heighten the reader’s awareness of that “forbidden” content in interesting ways. Have you noticed any differences in how readers respond to your work based on whether they first encounter it through a live reading or on the printed page?

Meijer: I haven’t really noticed much difference, except to say that I’m pleasantly surprised, both when I read to an audience and when I hear back from people who’ve read the book, that the subject matter isn’t that much of an obstacle for most readers. When someone is sitting down with you and telling a story, whether it’s theirs or someone else’s, I don’t think you respond to the subject matter in the abstract. There’s immediately a face to it, a voice. We look for ways to connect. If you’re trying to sum up some of the stories in the collection, it can sound like they’re a bit out there. But I think once you get into it it feels familiar–at least, I hope some of it does. I’m not writing science fiction, after all–there aren’t any aliens on the page. We’re all working with the same emotional palette, though the context for those emotions varies widely from person to person, story to story.

– Mara Bandy

MASANDE NTSHANGA

Masande Ntshanga has been generating a lot of buzz with his first novel, The Reactive, a book his American publisher describes as “James Baldwin meets Trainspotting meets Harmony Korine.” The novel opens with its narrator, Nathi, confiding that he is responsible for the death of his brother but not telling the reader exactly what happened. As we follow Nathi through his wanderings in Cape Town, South Africa, we learn that he is drifting by selling medicinal drugs with his friends to the many desperate people who have been let down by the government’s ineffectual response to the AIDS pandemic. Nathi’s journey touches on issues of class and race but ultimately most poignantly explores the question of what it means to grow up and become a man in a place where so many young people are dying. The Reactive was huge in South Africa and has received massive amounts of critical acclaim internationally as well, including being longlisted for the Etisalat Prize for Literature.

Ntshanga kindly answered a few questions via e-mail prior to his appearance at PygLit.

SP: The Reactive is set in 2003 during a period in which HIV-infected people in South Africa were having a lot of difficulty accessing the drugs they needed and the government was failing to adequately respond. What initially drew you to this particular moment in history as a setting for a novel?

Ntshanga: I think I was drawn to this era for two reasons. The first was that I remembered it as a time of receding optimism in the country, with a particular relationship to our generation X, whom, until that point, had embraced the mandate of egalitarianism and multiracialism that came from our newly liberated country. The second was because of the turnover in policy regarding the distribution of ARVs in South Africa. I felt it was something I could use to draw the parallel I had in mind between the personal and physical, as well as the political and national.

SP: What kind of research did you do?

Ntshanga: I always do my research in the editing stage, and for this book, most of it was a process of verification. I was surprised, in fact, to discover how much I had absorbed from what had always been in front of me. Perhaps, this is often the case with first novels, but this was more a process of extricating the material rather than setting out to collect it.

SP: The Reactive has a very strong sense of place and inspired me to look up a number of things about the history and culture of South Africa while I was reading. Have you encountered or do you anticipate any challenges when doing readings here in the U.S. in introducing the work to readers who may be unfamiliar with the story’s context?

SP: The Reactive has a very strong sense of place and inspired me to look up a number of things about the history and culture of South Africa while I was reading. Have you encountered or do you anticipate any challenges when doing readings here in the U.S. in introducing the work to readers who may be unfamiliar with the story’s context?

Ntshanga: Thank you. I’m glad it did. To be honest, I haven’t encountered any challenges. Many readers have been receptive to the work as is, which I’m grateful for, and some have even illuminated aspects of it I hadn’t yet considered. I think this speaks to the structure and content of the book, as I did want it to come out in such a way that there was no hierarchy imposed on all the parts that make it up as a whole. I think people, so far, have been able to attach themselves to the parts that resonate with them. In this way, they see the story through the lens that’s most fitting to them as individuals, and often, this means being receptive, or at least having a certain degree of comfort, with everything else around that that might remain a little unfamiliar.

– Mara Bandy

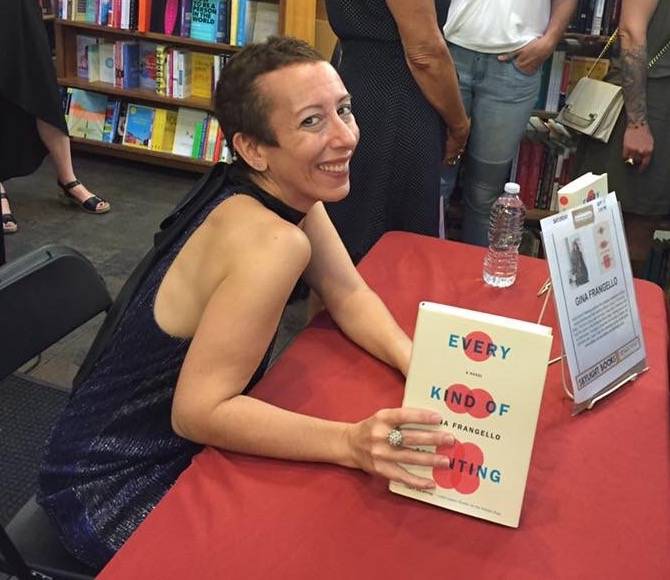

GINA FRANGELLO

Gina Frangello writes female-centric inclusive fiction that does not flinch – ever. Physical danger, emotional ambivalence, implied almost-mutual sexual predation, awkward familial interactions and more are waded through, armpit deep, no toe-dipping in preparation. Starting one of her novels is almost like what I imagine Quantum-Leaping to be. In both works I read, A Life In Men and the beginnings of Every Kind of Wanting, the perspectives shift among characters at chapter breaks, but when you’re reading a character you are completely absorbed inside their minds, almost past the point where you think a person could actually be self-aware and still sane. It’s an experience you almost need to be warned about in order to fully enjoy. Consider yourself warned.

When I spoke to Ms. Frangello, I couldn’t imagine actually getting more description about her characters or the plots, because I felt like I was beyond intimately acquainted with them already. I’d been inside their thoughts, feelings, illnesses, and lived through …just life with them. Weird, boring, sucky and satisfying life. Maybe a little quippier than a normal life, but hey, that’s a common “complaint” about fiction and if we told the truth we’d admit we’re just jealous.

Since she’s a reader in the “ShortShortShorts” program, I followed the theme and only asked her three brief questions.

SP: Selfish question first — I’ve read that you have 20 years’ experience as an editor, but it looks like you published your first novel only 6 years back. As a lifelong reader and a new editor myself, I feel very comfortable and confident helping others shape their work, but I rarely feel the pull to create a story of my own. For you, was it always the plan to write, and editing happened… or as an editor did you grow to feel it was time for your own story? What prompted the shift?

Frangello: My debut novel, My Sister’s Continent, actually came out in 2006, so a decade ago—it was on a very small indie press, Chiasmus, which was founded and then run by Lidia Yuknavitch (now of course a bestselling author). I gave birth to my son the same month the novel was released, so I didn’t tour much, and it was a pretty DIY indie without wide distribution. My second book, a story collection called Slut Lullabies, got a fair amount more media attention and I toured much more extensively behind it, so I became a little more visible at that point. But like many writers—most writers, I’d say—I was writing for many years prior to the release of my first book, publishing in literary magazines and doing freelance journalism…there was never a time I didn’t write. My editing and writing lives were deeply intertwined for 20 years. I continued to edit actively in the indie sphere after my own books were coming out, at the press I founded, Other Voices Books, as well as places like The Rumpus and The Nervous Breakdown, until just a couple of years ago. Now I’m focusing more on my own writing and on teaching, but that isn’t necessarily a permanent shift…it’s mainly out of economic necessity.

SP: Saturday morning’s event is for quick fiction, but I am most familiar with your novels and your journalism. What can attendees expect to hear from you during your reading? (an excerpt from your newly released book, perhaps?)

Frangello: Yes, I do occasional flash fiction, but I’m reading an excerpt from the new novel, Every Kind of Wanting, which centers around a gestational surrogacy and is an ensemble piece told in numerous points of view—so the book actually loans itself easily to short readings. The characters’ perspectives often contrast with each other’s, adding layers and resisting an idea of one central Truth around an event.

SP: The LitFest schedule seems rather nebulous at this point, so it’s hard to tell: are you involved with or participating in any other readings at the Fest?

Frangello: No, actually I’m driving down with two of my three kids and on the way our mission in life is to find some farm participating in National Alpaca Farm Days – because my son is obsessed with alpacas — and doing that before we hit the festival. I’ve found out a few lit friends I didn’t realize would be at Pygmalion will be there and am hoping to be around long enough to see people and enjoy the festival.

– rebecca knaur

That about wraps it up for the four readers who will share a 30 minute time slot first thing Saturday, inside the Accord, during the Book Fort. Local, regional, national, weird, intense, dystopian, foreign but all universally human. Come out to hear quick bursts of intentionally condensed performance at noon, during “ShortShortShorts”.