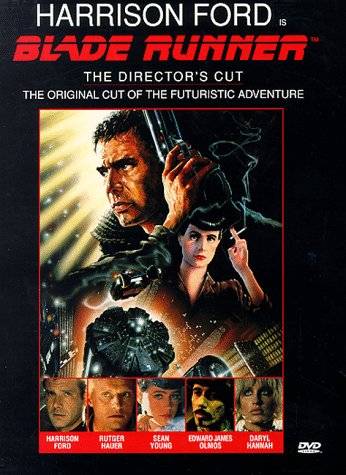

Recently, I was discussing with a friend the significance of the term “director’s cut.” Soon after the advent of home video and especially after DVD, “director’s cut” became a major selling point for the home video market. Originating, or at least popularized by Ridley Scott’s 1993 video release of Blade Runner: The Director’s Cut, the tagline was employed by Hollywood, which capitalized on its own reputation for suppressing original artistic expression.

Recently, I was discussing with a friend the significance of the term “director’s cut.” Soon after the advent of home video and especially after DVD, “director’s cut” became a major selling point for the home video market. Originating, or at least popularized by Ridley Scott’s 1993 video release of Blade Runner: The Director’s Cut, the tagline was employed by Hollywood, which capitalized on its own reputation for suppressing original artistic expression.

The concept of a Director’s Cut is directly related to the auteur theory first put forth by the critics-turned-directors (e.g., Jean-Luc Godard and Francois Truffaut) in the late 1950s. The idea that the director is the ultimate creative force behind a film is one that we generally subscribe to without a second thought today; but in their time, the idea that Howard Hawks’ films might be as Hawksian as Manet paintings were Manet-esque was revolutionary. The French New Wave was born from this theory, and America’s popular culture was not far behind. Hitchcock was already the Master of Suspense, but in retrospect, names like Welles, Capra, Ford, Cukor, Wilder, DeMille, Lubitsch, and many more took on new significance, while Spielberg, Coppola, Scorsese, Lucas, and DePalma were regarded as the new vanguard of American film.

But still, even after the demise of the studio era, it was widely understood that although directors may be the primary producers of “a vision,” the studios and their demands regarding accessibility and marketability were inhibiting true creative progression in Hollywood. Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner: The Director’s Cut was perhaps the first example of a movie studio implicitly admitting that they had inhibited the expression of an artist and were now willing to make amends by releasing his original vision. The 1993 home video and simultaneous (limited) theatrical release of the re-cut Blade Runner was a landmark of sorts. To the more optimistic cinephiles, it suggested that Hollywood was beginning to understand the importance of individual expression; to the pessimistic, it revealed that Hollywood would do anything to make its money back.

Blade Runner, in its theatrical cut, had been a dismal failure, despite starring the then-biggest star in the country, Harrison Ford. The studio had almost nothing to lose by releasing Ridley Scott’s preferred version. If it made no money, they were in the same position they had been 11 years before; if it made lots of money, all the better for them.

And while Director’s Cuts still do occasionally allow us to see the sporadic “original masterpiece” envisioned by a beloved auteur, most of the time they are merely marketing schemes. Take the multiple cuts of Oliver Stone’s 2004 film Alexander, for instance. Prestige directors like Stone typically get “final cut;” that is, they get to say what goes. Nobody tells Steven Spielberg or George Lucas what to cut out or leave in anymore; hell, even Bryan Singer (Usual Suspects, X-Men 1 & 2, Superman Returns, Valkyrie) gets final cut these days. Stone’s Director’s Cut of Alexander was a way to entice audiences who weren’t completely turned off by the atrocious original version to give the film another try. The Blu-Ray version is yet another cut of the same film, suggesting again through a perverted version of the auteur theory that this time, the film will finally be worth your time.

And while Director’s Cuts still do occasionally allow us to see the sporadic “original masterpiece” envisioned by a beloved auteur, most of the time they are merely marketing schemes. Take the multiple cuts of Oliver Stone’s 2004 film Alexander, for instance. Prestige directors like Stone typically get “final cut;” that is, they get to say what goes. Nobody tells Steven Spielberg or George Lucas what to cut out or leave in anymore; hell, even Bryan Singer (Usual Suspects, X-Men 1 & 2, Superman Returns, Valkyrie) gets final cut these days. Stone’s Director’s Cut of Alexander was a way to entice audiences who weren’t completely turned off by the atrocious original version to give the film another try. The Blu-Ray version is yet another cut of the same film, suggesting again through a perverted version of the auteur theory that this time, the film will finally be worth your time.

The rash of unrated films, especially among comedies, is along the same lines. Hollywood is attempting to capitalize on the idea that they prohibit the original intentions of the filmmakers from reaching the screen, but you get the sense that in the case of films like Forgetting Sarah Marshall, they withhold the “racy” footage with the intention of including it on the DVD as unrated. The Director’s Cut of American Psycho suggests this same thing in much more sordid ways, and myriad other Director’s Cut and “special” DVD editions offer few compelling reasons to spend an extra $30.

So be careful. If a film comes out every five years with a new edit — such as, for instance, Cinema Paradiso — do you really need to own or even watch each one? It is sometimes hard to tell the genuine reconstitutions from the vapid marketing ploys, and it is also important to understand that Director’s Cut, unrated, and Special Edition are not always indicators of improvement or quality.

New Releases From the Box

Beverly Hills Chihuahua

This movie made $95 million at the box office? Seriously?

Australia

This one got a spanking from the press, but I rather enjoyed it, for all its grandiose melodrama. It’s not particularly original, nor particularly historically or politically adept, but it’s a fun, overblown adventure by the director who knows hyperbole, Baz Luhrmann.

Watchmen Motion Comics

Maybe I’m just a purist, but to me it shouldn’t be a problem to spend your $30 on a comic book instead of a comic on DVD. What’s wrong with turning pages? Movies are fine, comics are fine, filmed adaptations of comics are peachy, but why do you need to watch a comic on your television screen? I blame Zack Snyder.

Next Week on From the Box

Interesting films are actually released: Gus Van Zant’s Milk, Mike Leigh’s Happy-Go-Lucky, Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, NY, Oscar nominee Rachel Getting Married, Apatow-esque comedy Role Models, and pointless sequel Transporter 3. How will our writer deal with this onslaught of quality? Probably watch one and conjecture about the others, next week on From the Box.