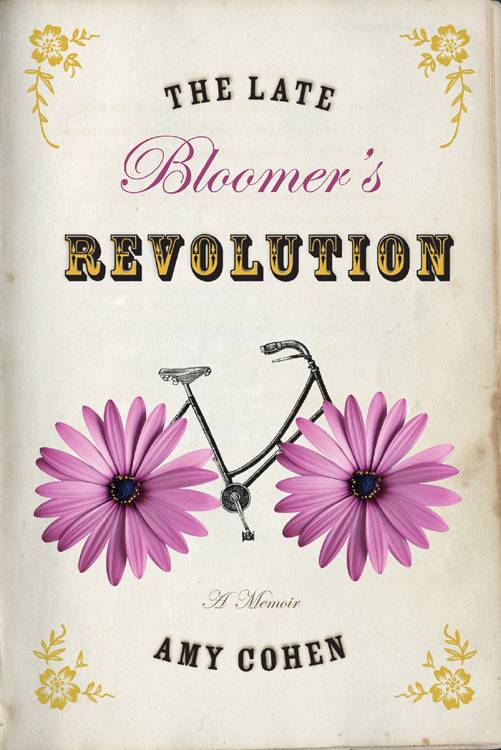

If your David Sedaris jones knows no nadir, you’ll be mollified to know that a virtual methadone exists. Amy Cohen’s The Late Bloomer’s Revolution is available on audio.

If your David Sedaris jones knows no nadir, you’ll be mollified to know that a virtual methadone exists. Amy Cohen’s The Late Bloomer’s Revolution is available on audio.

Amy is a brilliant, extremely single, highly Jewish New Yorker as seen on TV. Bloomer’s is a narration in the Sedaris tradition, a memoir of everyday events made poignant by an unusually insightful narrator. It’s also available in book form. But as with Sedaris and Garrison Keillor, Cohen’s performance makes great content exceptional. Her reading attains a rarefied level of comic epistemology.

Author’s note: I planned to avoid the words “David Sedaris” in describing it. I assumed she’d become haunted by the comparison. Terry Pratchett probably got bored with Douglas Adams comparisons until his sales numbers eclipsed Adams. Philip Pullman probably got bored with reading sentences beginning “If you like J.K. Rowling …” But she mentioned his name in our correspondence.* I took it as a tacit warrant. Sedaris, Sedaris, Sedaris!

Amy Cohen is a former (fired) writer for television situation comedies, and like our own local sitcom writer, her talents are thoroughly wasted in conventional LCD. She’s the youngest of three children, and although over (gasp) forty she’s still not married.

Amy Cohen is a former (fired) writer for television situation comedies, and like our own local sitcom writer, her talents are thoroughly wasted in conventional LCD. She’s the youngest of three children, and although over (gasp) forty she’s still not married.

WOMEN ARE FROM BARS, MEN ARE FROM PENIS

Amy was born in 1966. So I’ve calculated that by now she has spent 11 solid years of her life wondering why X guy dumped her, or didn’t call her back. Highlights from these years comprise the bulk of The Late Bloomer’s Revolution.

Problematically, she’s often searching for a rational explanation. Because I have testicles, I know that the answer is biological rather than intellectual. There’s an urge to get up and run away. Once a man seemingly tricks the female into sex, and planted the seed, the flight instinct kicks in. The male is biologically programmed to find the next mate, and impregnate her too.

With age, he calms down and realizes company can be comforting, and holding hands is actually really great. At that point, the male starts looking for someone he enjoys being around. He recognizes that big boobs are not a personality trait.

But when he’s young, he wants a lot of space. “Come here, come here, come here — oh get away, get away, get away” is how Bill Cosby described youthful relationships.

Amy presents her twentysomething self as assuming it’s her fault when a guy wants to move on. She offers to change.

The trick, of course, is to do exactly the opposite. When someone says he needs more space, the proper response is an airy, “Okay. Well, bye now.” That’s when the guy suffers a crisis of adequacy. This is called “hard to get” and “playing games.” It works.

But getting the upper hand only makes you feel better about yourself. It does nothing to improve the relationship. It doesn’t make people like each other, have more in common, or get along well. That’s a point Amy concedes: She didn’t really like the guy, but she wanted to be the one in power. It’s part of Amy’s transition from thinking she needs to have another person against/by whom to define herself.

The Marriage Industrial Complex, misogynist religions and the biological clock are social forces. Amy is frank about the pressure to get married. She acknowledges that it made her crazy, even as she fought against it.

She dishes on her desperation in various hilarious scenes. One involves the handsome, single, Jewish-Argentine medical student – evidently the five ideal adjectives – she meets on a European vacation with her mother.

His name was Miguel. His chapter in Amy’s story perfectly demonstrates the reason this book, while plenty good reading, must be heard — literally in her own voice. Read this excerpt. Then listen to the recorded version.

As we left the restaurant, Miguel said, “I hope to see you tomorrow,” adding clumsily, “both of you.”

My mother smiled as she waved good-bye.

“He’s in love with you,” I said.

“Oh, please. That’s ridiculous. That’s just the wine talking.”

“Yours or mine?” I said. “And I’m not spending the day with him tomorrow.”

“Fine. We’ll leave the hotel before he calls. Besides, you know those Latins. They’re like Italians. They’re all crazy about their mothers, and I’m sure he just wanted me to fill in. It’s actually very insulting if you ask me.”

All of these clips are funny, but it’s the timing and performance of her own material that makes this work exceptional. Here’s another example of her desperation, stuttered to perfection.

VULNERABILITY APPEALS

An author seeking to gain an audience’s trust should always show her warts. Bloomer’s is all about Amy’s warts. She also dishes about body fat, dorkiness, naïveté, neuroses and slowness to catch on. It’s compelling stuff, and hilarious; it proves again that forthrightness about problems, insecurities and blemishes wraps listeners around your finger.

Amy’s blemishes showed up not long after her mom died, and just after she got dumped… and then fired. Big, red patchy welts overtook her face.

Her dermatologist suspected a particular cause. But to rule out allergies and exposure, he advised her to spend the year indoors, eating nothing but steamed vegetables. This is where the story gets seriously funny.

This interview with Claude is one of two skin-problem episodes involving wacky east Asians. The other is Sun-Yi, the Korean laundry lady. It occurred to me that doing ethnic comedy might seem less politically incorrect if the protagonist is suffering horribly. It works.

Amy also talks about her skin problems with her dad. This scene provides Amy an opportunity to demonstrate her “older Jewish man” impression, which she repeats in a scene at the dermatologist’s office, adding extra chutzpah to the characterizations on account of those two Jews being Orthodox.

TIMIDITY DOES NOT

The thing everybody loves about David Sedaris is that he’s offensive. While he breaks barriers, he doesn’t even acknowledge them. Fuck barriers.

That’s the correct attitude.

The thing everybody loves about Garrison Keillor is that he allows you to accept your ridiculous Midwestern parents. You feel as if your Midwestern upbringing were perfectly normal, which it was — not to say it was good.

Armed with these same weapons, Amy Cohen strikes at your heart. It’s okay if you capitulate. There’s no penalty for admitting you are who you are, as long as you are okay with it. Cohen’s gift to humorous psychology is pathos. She’s hyper-aware of people’s feelings, including her own. Thinking through her feelings took the first four decades of her life. A pessimist would say she wasted all that time. When being pessimistic, she says that.

The Late Bloomer’s Revolution is HER story. That is, it’s less a manifesto than its title suggests, and more an autobiography. It’s not about empowerment. That’s up to you. It’s about sadness. That’s the odd attribute of the funniest book I’ve heard this year.

Or maybe it’s not odd. I’ve always argued humor is the best lens through which to inspect the human condition. Recent media phenomena indicate humor is also a better way to communicate information. Fans of The Daily Show with Jon Stewart, Real Time with Bill Maher and The Onion are smarter, and better informed than the general public, according to serious sources. Maybe those media communicate news better than “real news” sources. The National Enquirer and TMZ continue to break stories which other outlets won’t touch.

Whatever the psychoanalysis, Amy Cohen is endearing and sad and inspiring. Her work involves Truth. Her contribution to humanity touches the ephemeral and the metaphysical. And wow, is that the important lesson: whatever it is, it’s only here for minutes, so pay attention. Know it.

But I am not the only judge of her contribution. The Marriage Industrial Complex, religious institutions and maybe even TMZ want to know why she’s single and childless. If those are benchmarks of a life well lived, then let’s all kill ourselves. Given those parameters, our species is going nowhere.