is for X-perimental. It’s to be X-pected to break the rules a bit when it’s time to honor this mysterious cipher.

is for X-perimental. It’s to be X-pected to break the rules a bit when it’s time to honor this mysterious cipher.

X takes us to hidden treasure: X marks the spot. It warns of what’s beyond the polite: X-rated. It signifies the unsolvable: X-files.

Without much digging, you can bump into all three in Champaign/Urbana. Grab your hat, take a deep breath, and come X-plore.

One of the more vibrant experimental think-tanks in town is PaleGray Labs, at the Water Street entrance to the County Building in downtown Urbana. Just inside the door you’ll be met with the odd almost musical humming of a giant quilting machine hard at work — stitching intricate patterns designed by Nina Paley and converted to robot language by Theo Gray. Computer programming meets traditional handcraft in the creative frenzy of “co-lunatics” Gray and Paley, who co-produce king-size quilts with the mechanical talents of their Quilt Master IV full-frame Quilt Plotter — known in the family as Behemoth. Paley began with traditional quilting but quickly moved into challenging designs that require more mechanized power – and so she researched the best mega-machines for quilting, manufactured in China.

To program Behemoth for continuous stitching, drawings for the quilts must be converted to “single line art” to avoid stops and starts that require cutting and trimming threads by hand. Behemoth arrived with a crude computer for its patterns; here’s where Gray got intrigued. Programming savant, for him the greater the challenge the better. He put Mathematica on the job (more on that later) to optimize the pathway so that Behemoth can chug out the most complex patterns. And what more challenging design than the $1000 bill?

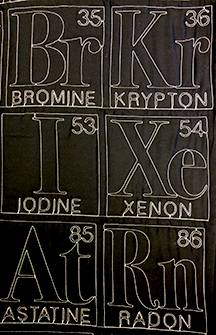

It takes two days and 360,000 stitches to produce this lovingly translated version in 100% cotton that promises to keep you warm at night. Paley and Gray have figured out how to mechanize the process to the point where quilted currency and other witty and beautiful designs can be produced to order. Read all about it and concoct your own word-quilt with PaleGray. The “X” that opens this article is a detail from their glow-in-the-dark counterpane of the table of periodic elements.

Working with robotic stitchers is only one of Gray’s more recent experiments. Back in the 1980s, he and Stephen Wolfram teamed up to develop a computer language and engine sophisticated enough for high level physics. Gray’s contribution was to provide a user interface that makes it a convenient tool. The result, Mathematica, issued in 1988, earns its moniker as “the world’s definitive system for modern technical computing,” where “computation meets knowledge.” It has inspired and enabled a dizzying array of computational creativity, expanding as we speak into Wolfram|Alpha Pro and beyond in the offices at 100 Trade Center Drive in Champaign.

Trained as a chemist but more naturally gravitating to computer programming, Gray has pursued many such “experimental” avenues, often inspired by the challenge, “can it be done?” A fascination with the periodic table of elements led him to design a genuine wooden table to display samples of each one. And given the beauty of these primary building blocks, why stop there? With Nick Mann, a local photographer always up for a challenge, Gray devised a rotational system to simulate 3D photography that displays each element in 360-degree glory. He published this in book form as The Elements.

For a visionary, one good idea often inspires another. Gray enjoys the beauty of touch technology, so well captured in the ipad, and so he assembled a team to develop an app to bring The Elements into hand-held experience. From there he moved on to molecules, and the result brings you ever-so-close to being able to “touch, stretch and twist molecules and discover how everything is made.” That inspired him to co-found TouchPress, based in London, now busy developing other experimental and highly rewarded apps for your delight. Experience what it’s like to conduct an orchestra, score in hand; or challenge yourself to think like Churchill; or spend a day as an apprentice architect. Are you intrigued? Take a look.

Here are Gray and Paley at their lab: Gray explaining their ten-needle embroidery machine, and Paley doing the finishing touches on a quiltamation piece based on the running horse photographs of Eadweard Muybridge (yup, it’s really spelled like that).

Gray’s inventiveness goes far beyond these x-ploits – as a long-published writer for Popular Science, he’ll take you on a journey with detail and skill on his website and through blogs devoted to his different interests. They make for inspiring reading.

———

Let’s look more closely at that word “experimental.” C-U is, after all, home turf for one of the leading Research-One universities in the country. And so to understand the rigorous requirements for scientific experiments, I paid a visit to the Infant Cognition Lab in the Psych Building at 6th and Daniel. A steady stream of local infants and toddlers passes through their cheerful offices, as the subjects in ever-evolving studies that are slowly teaching us just how those mysterious little brains perceive and comprehend the laws of nature and society.

Since 1984, 25,000 babies have been the audience at small dramas staged in the lab, where they sit before scenes such as a block mysteriously floating in air when a hand releases it, or a tussle between two puppets over how many cookies they’re willing to share. The length of time a baby looks at a scene reveals what she perceives as normal, in contrast to what surprises her. How and when does a baby understand the laws of gravity? What does he consider fair behavior between puppets who are alike and different?

Here you see lab administrator Jackie Aldridge and her daughter Genevieve watching an experiment called “Amigos.” A monkey and a dog are side by side. The monkey has three apples; the dog has three lego towers. Uh oh! The dog takes an apple from the monkey. What’s the appropriate response? The baby isn’t surprised if the monkey knocks over two of the dog’s towers. But if the theft is between two monkeys — an example of in-group behavior, versus out-group — the baby is more likely to anticipate a milder reprimand – knocking over just one tower. This explores sociomoral reasoning. Other experiments focus on psychological, physical, and biological understanding.

Questions such as these have been under the rigorous scrutiny of Dr. Renée Baillargeon over the 30+ years she has directed the lab. She is a wise master of the Scientific Method, painstakingly collecting data from babies’ responses to intricately staged scenarios. When the results are surprising or unclear, she will devise similar but subtly different experiments to reveal more specifically just what the baby is thinking. Observers record precise “looking times,” the results are statistically analyzed; hypotheses are examined, disproven, revised, confirmed. It is a dance of patience, ingenuity, discipline, and generosity as generations of students pass through the lab, learning the discipline, rigors, and creativity of scientific experimention.

Baillargeon loves to be surprised by what babies do. To her what’s important is not her hypothesis but what the experiments actually reveal. She will design a number of ways to look at the same question; when several of these deliver converging evidence and thus verify a hypothesis, she is one step closer to the truth.

She has been named a fellow in both the American Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Sciences for significant contributions to how we understand infant cognition. One of her many pieces in Developmental Psychology is #15 on the list of “20 Most Revolutionary Studies in Child Psychology published since 1950.” Another cheer for Illinois!

She has been named a fellow in both the American Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Sciences for significant contributions to how we understand infant cognition. One of her many pieces in Developmental Psychology is #15 on the list of “20 Most Revolutionary Studies in Child Psychology published since 1950.” Another cheer for Illinois!

Baillargeon appreciates the cumulative nature of science. Across each researcher’s career, the aim is not personal fame but to build on the work of those who have gone before and contribute a solid piece to the growing structure of what we understand about the field. Her continuing fascination with just how babies learn about this world inspires her to focus on the most important questions and concoct the best possible experiments to explore the answers.

And if you have a child between four months and three years, be sure to join in the fun!

———

How does the idea of the X-perimental cross into the arts? If you have your antennae up for challenging literature, you may well have encountered the offerings of Spineless Books, the brainchild of William Gillespie, local writer and indefatigable innovator.

Gillespie has devised with no less rigor than a scientist some startling techniques to “avoid stale language to create a new and more vibrant meaning.” He did me the favor of spelling out his schema.

“In science, an experiment aims to support a theory through reproducible results. The same experiment yields the same outcome each time. An apple dropped from the Leaning Tower of Pisa will always fall at 32 feet per second squared. From this truth we can deduce the power of gravity.

In art, an experiment aims to create irreproducible results. The same experiment yields unpredictable outcomes. A novel written without the letter “E” — for example Wright’s Gadsby or Perec’s La Disparition (or its English translation Adair’s A Void) — will always be different. More important, the result will be wildly different than any novel that uses the letter “E” freely, because the experiment blocks and filters clichés.

I want to emphasize that my definition of experimental writing means following a technique as rigorous, hermetic, meticulous, and explicable as a scientific experiment. I do not consider writing experimental that is simply crazy, wasted, unintelligible, free-form, or a style that differs from the author’s normal mode. I don’t consider experimental writing valuable unless the writer reveals the experimental process.”

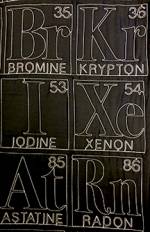

Gillespie and Nick Montfort were inspired by the symmetry of the approaching 2002nd year to expand on palindrome — a word or longer sequence that reads the same backward and forward. I offer for your enjoyment the opening words of 2002: A Palindrome Story:

“2002 demands lore — aside Roman-era eye, non-idyl. Guerilla muse, we call, rig. Yo! Brag us an ode- tale. O readers, meet Bob. (Elapse, year! Be glass! Arc!)”

And amazingly those same characters reverse themselves for a breathtaking conclusion:

“Crass algebra. Eyes pale, Bob teems red, aero-elated on a sugar: “Boy … girl lace!” We sum all: ire, ugly din. One year enamored is aero-LSD named 2002.

The design of the physical book mimics the text. Building on the title, since 2 + 2 and 2 x 2 deliver the same result, the book must of course be 4” x 4”. Designed wittily by Ingrid Ankerson, it has five illustrations by Shelley Jackson that are designed to reverse themselves: two in the first half, one at the pivot point of the central “X” of the book, most provocatively a sex scene. And the last two do palindromic honors.

And yes, the X in the pivotal center delivers an incisive oxymoron as it disappears in the spine of a Spineless book.

To develop such a feat took the full year of 2001, with Gillespie and Montfort writing their own bits, sending them forward and backward, editing, and recombining. They developed their own software, Deep Speed – of course a palindrome! — that stands ready to test any sequence you type in for the necessary symmetry. It will helpfully reverse your letters to ease the process. How can you resist giving it a try?

The Spineless website, a literary tour de force in itself, is well worth a visit. With that, Gillespie earns the last word on X-periments in writing.

———

Add a stage to artistic experimentation, and you find yourself with three dimensions to work with, and add that inevitable ingredient Time. The possibilities X-pand.

C/U is a city that offers many stages, with performers only too pleased to push the limits. If you haven’t yet had the pleasure, let me introduce a local duo who devise surprising and thought-provoking performances in a process uniquely their own. Lisa Fay and Jeff Glassman work in movement-based theatre that takes apart the actions of every-day life and puts them back together in unfamiliar and surprising forms. These unfold to expose the underlying language and reveal surprises about how we human beings bumble through daily life. Performances by the Lisa Fay and Jeff Glassman Duo are amusing, thought-provoking, and challenging.

These two explore the vocabulary and expression of “embodied composition.” They work in the largely unexplored elements that make up daily behavior, breaking them down to the tiniest details and using these as building blocks, like musical notes, to compose highly stylized performances. Their work resembles mime but has added dimension, sometimes like the step-action of animations. To see ordinary behavior transformed into something unnatural disorients the viewers; and there lies the beauty of experimental theater. It makes its audience participants in pondering just what This Human Condition is all about.

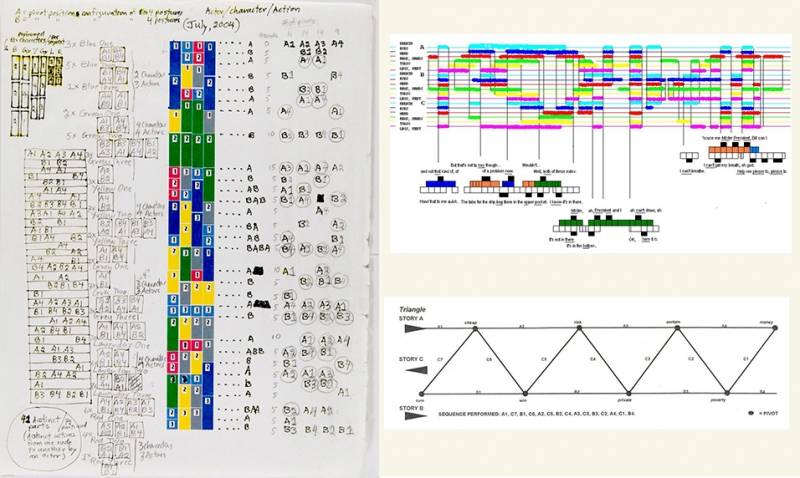

Each piece is its own experiment. In exploring how best to choreograph the components that make up a scenario, Fay and Glassman devise the language and graphics they need to represent the pieces of that particular performance — movements, dialog, story, timing — and how those fit together. An understandable and reproducible score will make it possible for a group of actors to collaborate, compose, edit, revise and then precisely perform the finished composition on stage. Three samples from their website show how different the score can look for different pieces.

Fay and Glassman have toured as performers and teachers world-wide since 1991, journeying as far as Mexico, Cuba and South Korea. As theatre artists, they produce their own compositions. When they teach, they work with participants and their stories to write scripts, and then devise ways to apply unusual formal structures that recreate them as performed experiments. In this way form and content can become a kind of Mobius strip, where first one is prominent and then the other, without a visible transition.

Their most recent community collaboration, produced while they were artists-in-residence at Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, was a pilot project called Theater of the Hummingbird, resulting in a youth-driven production of the participants’ own creations, performed twice locally in March. The six participants created the content, stories, observations, concerns and matters they felt important to address from their daily lives or the lives of others. Fay and Glassman taught the skills and language to script performances and to give young people the time and place to be “taken seriously in public.”

Have you ever had that dance with a partner — or even inside your own head — around an enticing book you’ve checked out of the library? You haven’t taken the time to explore it, but the due date is tomorrow. It is the insight and the genius of Fay and Glassman to hone that interaction to its comic essence. Their precise performance reveals the underlying humanity, and even profundity, of small daily banter. Join the delight of the South Korean audience sharing this piece.

The careful thought and analysis Fay and Glassman bring to their work opens up new ways of looking at just what it means to “experiment” — whether it’s in theater, computer programming, or a psychology lab. Rather than scientific inquiry, they expose the hidden power of everyday simple acts. Their innovation lies in how they dissect these actions into their smallest pieces and then put them back together in incrementally different ways. Like scientists they observe and measure the results; and make small changes to see what happens. They show us “how” we do what we do. The “why” behind that is the gift the audience receives to take home and ponder.

———

C-U is a most creative community; I’ve admired far more local forays than I could include here. I wish you a beautiful and creative experiment of your own to build a buzz and x-pand your horizons. Perhaps we’ll cross paths somewhere on that mysterious X.

I’ll close with a favorite ditty by a true original American philosopher, Kurt Vonnegut. From Cat’s Cradle:

Fish gotta swim

Birds gotta fly

Man gotta sit and wonder why, why why.

Fish gotta sleep

Bird gotta land

Man gotta tell himself he understand.

———

And just how did X get to be the 24th letter of our alphabet?

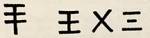

Around 1000 BCE, the Phoenicians developed the letter shown at left for their “s,” called samekh, meaning fish. This migrated into Greek, assuming the 3 forms at the right, and was renamed xi. From there it came directly through Latin as “x”, used also as the Roman numeral for ten.

Words in English beginning with x occupy only two of the 1550 pages of the American Heritage Dictionary.

———

Cope Cumpston is a typographer, book designer, and community enthusiast resident in Urbana. You can reach her here.

The archive of abecedarian C-U lives here.