Nestled just east of the Busey Woods off of Coler Avenue in Urbana is a small building with an equally small gravel parking lot. Unlike the large metal and glass structures further west along County Road 1700, the building looks much more organic, like it belongs in the woods instead of an industrial park. It feels quaint, nearly antiquated, as though there should be a stonework chimney sending a thin column of smoke into the sky. But the signs out front inform of its true purpose: CU’s only bookbindery. The Lincoln Bookbindery.

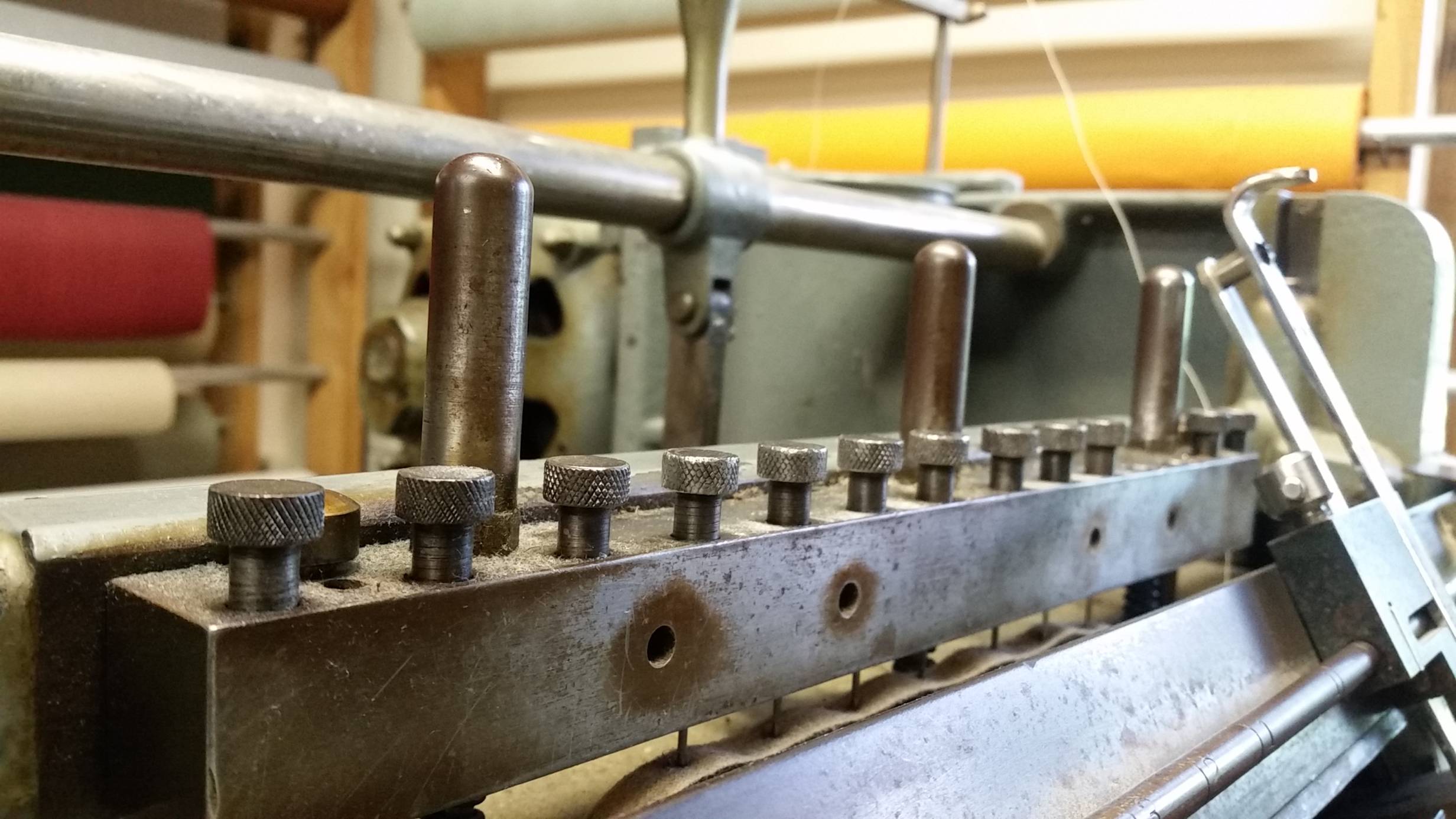

The small and unassuming Lincoln Bookbindery building belies what it contains. At any given time between 7:30 p.m. and 5:30 p.m. Monday through Friday, you’ll find either Christopher Hohn (owner) or Tedra Ashley-Wannemuehler (bookbinder) exercising their craft. The interior, lit jointly by cool fluorescence and warm natural light, is full of the tools and raw materials of the trade: pencils, scissors, rolls of cloth, and, of course, piles of cover-less pages ready to be professionally bound. The shop floor’s tables are punctuated by great metal machines, some cast iron, and few created after the middle of the previous century. To some extent, the business feels as much like a living history project as anything else.

“These old machines are still the best technology available for what we do,” Tedra told me as she rolled glue onto the backing cloth of a book block (the sewn pages of a book awaiting their cover). “For the kind of specialty work we do, these old machines are the pinnacle of technology.” That specialty work is, of course, binding (and occasionally repairing) books by hand, one at a time.

“These old machines are still the best technology available for what we do,” Tedra told me as she rolled glue onto the backing cloth of a book block (the sewn pages of a book awaiting their cover). “For the kind of specialty work we do, these old machines are the pinnacle of technology.” That specialty work is, of course, binding (and occasionally repairing) books by hand, one at a time.

The bindery has a long and storied history here in C-U. In the early 1960s, Lincoln Bookbindery was owned and operated out of a garage by a man named Donald Alexander. Sometime in the middle of the decade, Donald moved the bookbindery to a rented warehouse space at 811 Lincoln Avenue. By the end of the 1960s, however, the business had failed, been repossessed by a bank, and sold to Shirley and Paul Hursey of Urbana.

This is where the story becomes relevant to the present day, for in 1972, Christopher Hohn began working for the Hurseys as a sophomore in college. He stuck around at the Bindery, running it with Shirley and other employees (while Paul returned to a position at U of I) until 1978, when he and his wife decided two things:

- they were going to stay in C-U, and

- due to the amount of time he was spending at the shop, he needed to either own the business or take his Graphic Design credentials elsewhere.

The Hurseys came to an agreement with Christopher, and on May 4th, 1978, he became the owner of the Lincoln Bookbindery.

By 1983, the bindery’s building was under new management and falling into disrepair as rent continued to increase (a predicament many people in the C-U area are intimately familiar with). Christopher bought a plot of land, built a fresh structure, and on July 16th, 1984, opened the bookbindery for business in its current location.

Each step in the bookbinding process is performed in almost the exact same way as it has been since Christopher started working there in the 1970s, and probably way before that. Rebinding antique books and creating new, quality books that will last for generations takes care and effort.

First, the pages arrive, brought by either a client or a printer. These leaves of paper and print are then sewn together on the bindery’s vintage 1930s sewing machine. After the pages are sewn and folded and have had end papers (blank sheets at the front and back) glued on, the uneven edges are trimmed. Then the book block is taken to one of the Rounder Backers, which either (in the case of the later hydraulic version) squeezes it in a hydraulic press before the bookbinder rolls a cylinder to round out the spine of the pages, or (in the case of the late 1800s screw-vice version) is squeezed in a vice before the bookbinder rounds over the spine with a hammer.

After the back of the book is rounded out, the bookbinder glues on small pieces of cloth called headbands and a large piece called the backing cloth to the rounded edge. These are partly decorative and partly to reinforce the pages’ attachment to the cover of the book.

Once the backing cloth is adhered, the book block is measured and cover boards are cut to size. Cover boards are the hard, high-density pieces of cardboard used for book covers that are even denser than some woods, allowing hardback books to take a considerable amount of punishment without wearing and to make your backpack rigid enough not to squish the sandwich you packed for lunch.

After the cover boards are cut out from a larger piece, the cloth (whichever color and material is going to be used for the book) is measured and cut by hand using special tools and measuring devices. Then the cloth is glued onto the covers and folded over the edges in a hand-fed machine that looks a lot like a fancy version of an old laundry wringer. The book and the cover generally sit out to allow the glue to dry.

Some time later, the end pages of the book block are glued onto the cover and the titles can be stamped into the cover and the spine using real metal leaf in a 250 degree Fahrenheit press.

This, of course, is just the process for making a simple book, something like a bound thesis. What sets the Lincoln Bookbindery apart from other bookbinderies are their small-quantity abilities (they can make just one book) and the fact that they work with their customers to help realize their visions when it comes to the binding.

Custom book making is something Tedra has been doing since she was an undergraduate at Indiana University. At first, it was just making books and book boxes for friends, and when she and her wife moved to C-U in the 1990s, she would drop by the Lincoln Bookbindery to buy supplies to keep making them. As time went on and she spent more and more time at the bindery, she and Christopher decided in 1997 that it was about time she officially became an employee of the bookbindery.

Tedra truly enjoys the work for a variety of reasons. “Chris is wonderful to work with,” she said, “we have the best working relationship I’ve ever had. We’re both actually low-drama type people, and that means that our partnership just works.” The bindery is also very community-focused. Other than being locally-owned, the majority of its clients are local, too, despite the fact that it has bound books for people in nearly every continent.

“This place has something of a barbershop vibe to it,” Tedra said with a smile. “People will drop by and talk with us for an hour or so while we’re working. It’s great. Working here, you get to meet all kinds of people and do all kinds of projects.”

The University of Illinois is still the bindery’s single biggest client, in one way or another. Back when students were required to have physical copies of their theses, the Lincoln Bookbindery did a lot of business. Now, according to Tedra, it’s rarer, but it still happens.

“Sometimes,” she said, “someone will come in and say, ‘I need a printed copy of my thesis – my advisor says I have to do it’. It’s more of an exception than a rule that people need high-quality print editions of their thesis. I assume that people just don’t see the point in having a physical copy sitting on a shelf, especially since a digital copy can sit on a harddrive somewhere.”

The shift from physical books to digital is affecting the bindery in more ways than I first thought. Not only are fewer people coming in to get a thesis bound, but fewer people are coming in to get things like family histories or self-published books bound. Furthermore, due to the shift to e-readers and tablets in schools, the bindery’s usual summer work of repairing or re-binding textbooks for local school districts has been tapering off. “It’s usually cyclical,” Tedra explained. “For a period people will be really into the idea of getting things published. Like in the late ‘90s and early 2000s, people started getting interested in self-publishing again. People would even bring in stacks of emails to get bound. But now, interest is sort of fading, and that doesn’t just affect the jobs we get, it also affects our ability to get supplies.”

That’s something I didn’t think of until speaking with Tedra. The general lack of interest in physical copies of books means that the companies that make things like book board for hardback covers and cover cloth have either gone out of business, reduced their production, or stopped selling in small quantities. The bindery’s suppliers list is becoming shorter by the year, and they only stock a portion of the cover cloth colors and materials they used to simply because they cannot obtain them anymore. “It’s a really good basic book that we make,” Tedra lamented, “and I don’t want to lose it. I’ve been doing this for 19 years now, and I don’t want to have to find another career.”

Still, the book bindery carries on. Remarkably, not only do they perform good work, but they do it quickly. It’s often said that out of Good, Fast, and Reasonably Priced, you can only pick two for any product or service. I would argue (based on my experience in printing) that the Lincoln Bookbindery has found some supernatural way to hit the trifecta. Their turnaround time for binding something is about one to two weeks. That’s a fraction of what other places can do, and for a price that is either comparable or even lower than what I’ve seen.

According to Christopher, the bindery’s record for number of books bound in one week is 275, an impressive number, though not too much higher than their usual “busy season” average of 100-200 a week. Now, due partially to waning interest and partially to the fact that many of their would-be clients get money from the state government (which can’t get its act together long enough to figure out its budget), the bindery is performing about half of the workdoing they used to. They’ve taken to rebinding more old books and trying to build more book boxes to keep business coming.

I’ve alluded to this before, but I’ll mention it again: another thing that sets the bindery apart is that they are the workshop of Tedra’s company Fine Blank Books, where she makes amazingly artistic products for her clients. With their tools, years of training and experience, and their eye for aesthetics and design, Christopher and Tedra don’t just bind utilitarian pieces – they also create beautiful works of art.

“My favorite thing about this job is getting interesting custom work,” Tedra said. “I love it when someone emails me or comes in and wants to work with me to make something really neat and new. It’s the ability to exercise creativity and to really produce a physical manifestation of someone’s vision that helps keep this from becoming too monotonous.”

The Lincoln Bookbindery really does see all kinds of work. Sure, there’s the standard thesis binding, or the re-binding of a textbook or some old family heirloom, but they have also crafted wedding guest books, photo albums, novels, poetry collections, and custom textbooks. If it can be bound, they’ve probably made it.

So if you ever find yourself thinking, “Boy, I sure wish there was some way to get a really cool bound edition of this thing I wrote,” or, “If only there was somewhere I could get a custom box made to fit this valuable book I have,” or, “I wonder what I could get as a gift for the writer in my life who has everything,” or even, “I wish I knew more about how books are bound,” then please head on over to the Lincoln Bookbindery. They’re local, invested in the community, and some of the nicest people you’ll ever meet.