There are people in town making very particular studies of what makes us Who We Are. Come see what they’re up to.

For LaKisha David, what she didn’t know about her own family compelled her from North Carolina to MIT and now U of I’s Department of Human Development and Family Studies. Names and places quickly fade before 1865 with the vagaries of slave records in the U.S. It wasn’t until the 1870 U.S. Federal Census that African-Americans were officially recorded by name.

For LaKisha David, what she didn’t know about her own family compelled her from North Carolina to MIT and now U of I’s Department of Human Development and Family Studies. Names and places quickly fade before 1865 with the vagaries of slave records in the U.S. It wasn’t until the 1870 U.S. Federal Census that African-Americans were officially recorded by name.

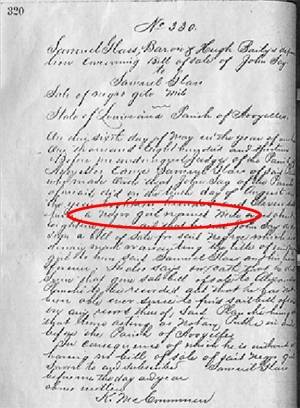

LaKisha’s mother raised her with a hunger to learn as much as she could about both her own family and their wider heritage, but conversations at family reunions reached only as far as mention of a book that told a piece of their story. Painstaking sleuthing led her to the Louisiana History Museum in Alexandria where a librarian joined the effort and identified The Lacroix Descendants, 1611-1991. LaKisha sought out the author, E. W. McDonald, an 88-year-old white aerospace engineer with a deep southern drawl, and claimed his last copy. In six critical pages out of 606 she found a name and the beginnings of a narrative in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana. In 1811 a slave named Milo was sold to Samuel Glass and bore him four children. Milo was LaKisha’s third great grandmother, and her youngest son, freed in 1865, her great grandfather. It was a dramatic moment when a friend laid her hands on Milo’s original bill of sale in courthouse archives in Marksville, Louisiana.

More records trace Milo’s sale away from her own children, and her named changed to Tamar.

LaKisha sent a saliva sample to AncestryDNA and plunged farther back, finding sure links to the Fante people in Ghana, where she is this summer with her mother. As individuals add their DNA results, a tree is leafing out to show seven branches out of Africa that link to the translatlantic slave trade. Sources including AncestryDNA and 23andMe provide contact information for people with a DNA match, leading to unexpected and life-changing reunions.

In March LaKisha created The African Kinship Reunion, TAKir, to widen her network and share an expanding toolkit. She grounds her work in real neighborhoods, including Champaign-Urbana, since the human aspects of community and individual health are at the core of her studies.

She knows firsthand what research shows: people who research their identity have stronger psychological balance. TAKir supports DNA analysis; as personal stories and lost connections emerge, it records and spreads them through blogs, podcasts and more. Each year it hosts a reunion in a different city, to make the network personal. It is a painstaking, longterm process that makes use of oral histories, family reunions, courthouse records, crumbling ledgers of bills of sale, census records – and chance discoveries. It is playing its part to mend the racial divisions across continents. This summer LaKisha is encountering stories of the African side of slavery and folding them into what TAKir can reveal about families and connections that reach across continents.

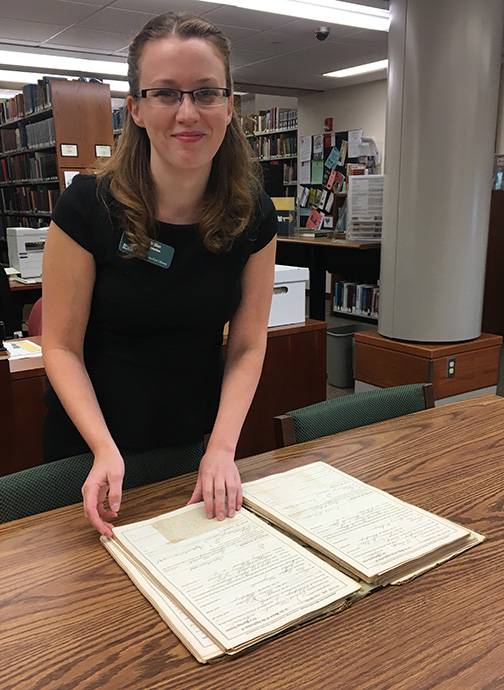

Without leaving town you can pursue your own past. How many great-grandparents can you name? Enter the active sanctum of the Champaign County Historical Archives, on the second floor of the Urbana Free Library, and you may be surprised by the wealth of expertise and documents at hand. The staff are only too pleased to guide you through a search, whether it’s ancestry or local history; you don’t need a library card or an appointment.

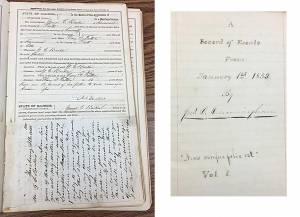

Since 1987 the Archives have been the official repository of non-current records in Champaign-Urbana, with a room stacked full, including gorgeous leather-bound volumes of birth certificates, marriage records, wills, court archives, sheriff’s records: the stuff of rich stories. Serendipitous discoveries are at your fingertips, such as the daily adventures of Joseph O. Cunningham (yes, he of the Avenue, the Children’s Home and more).

Since 1987 the Archives have been the official repository of non-current records in Champaign-Urbana, with a room stacked full, including gorgeous leather-bound volumes of birth certificates, marriage records, wills, court archives, sheriff’s records: the stuff of rich stories. Serendipitous discoveries are at your fingertips, such as the daily adventures of Joseph O. Cunningham (yes, he of the Avenue, the Children’s Home and more).

One gleeful researcher showed me a story under his newspaper pseudonym Racso, from his middle name, Oscar.

Donica Miller, Archives Librarian, who focuses on archive and record management, gave me a vivid and insightful introduction to the treasures at the Archives. She pulled out a tantalizing volume marriage certificates.

Note here a letter from the bride’s father granting permission for the union.

Many records are microfilmed or available online. Miller archives and organizes a growing collection of handwritten journals that tell the daily details of past life on the same streets we walk, from the Cunningham diary to the travel adventures of Julia Burnham, another familiar name.

Miller particularly enjoys first-time visitors who don’t know where to start a family search, whether it’s local or farther afield. She can pinpoint the most likely resources, guiding people to online sites such as FindAGrave or Cyndi’s List, a useful survey of genealogical tools. Fold3 is the source for military records, named for that critical last fold in the flags given to veterans’ families. Urbana’s archive is also an affiliate of the Mormon-based Family Search Research and Library System, the comprehensive collection based in Salt Lake City. It reveals billions of records of birth, marriage, death, census, land and court records from over 130 countries. Miller herself has caught the bug; she’s discovered unexpected links in her own family tree. Dip in, and you may be tempted to join her.

A good time to visit is Wednesday evenings between 7 and 8:30, when volunteers from the Champaign County Genealogical Society are on hand to help. They know the field and are savvy advisors. They can put you in touch with local experts if a search on your own seems daunting. The Society holds regular meetings on Tuesday evenings, both their own and open sessions about particular topics in ancestry research. LaKisha David will talk about her ancestry research on October 13.

In explaining the science of DNA, she led me to the U of I lab of Prof. Ripan Malhi, internationally known for his skills in untangling the secrets of ancient nucleotides. He has worked extensively with Native American peoples — ancient and historic, individuals and groups — tracing the first humans who crossed to this continent from Siberia some 15,000 years ago during the last ice age.

Human remains can be sacred, and cultural beliefs must be considered when probing ancient pasts. A major failing of genomic researchers has been to disregard the concerns of the indigenous people whose DNA they analyze and whose ancestors’ remains they sample — and to fail to consult them in ongoing studies. Ethical violations have made Native Americans reluctant to participate in the ever-widening potential of genomic research. Malhi has tackled that divide head-on, partnering with Native American House on campus to open access for indigenous students to labs, high-level technology, and mentoring. In 2011 he established the Summer Internship for Native Americans in Genomics, known as SING, with Native American House, the University of Texas at Austin, and other campuses that foster both genomic science and indigenous studies.

Participants in SING explore the uses and misuses of how genetic research can impact their communities, and get hands-on experience in the most advanced techniques of genomics and bioinformatics. Malhi is gratified to see a growing community of indigenous genomicists, who can play advisory and leadership roles as this science expands into terra incognita, both past and future.

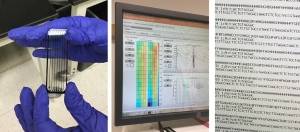

Malhi and his students analyze bone and teeth samples from ancient individuals, extending from British Columbia and California south to Panama and Peru. They organize them into “libraries” for the sequencing services at the Biotechnology Center in Madigan Lab off West Gregory, to confirm whether there’s readable DNA, intact over thousands of years. They work with units in the millions of SNPs — single nucleotide polymorphisms — to show the most basic units of human inheritance. Our Biotechnology Center is at the forefront of sequencing technology, serving research projects all over the globe. Chris Wright, assistant director, generously traced the process for me, from samples in flow cells through scanning in their high-end Illumina Sequencers. The final result? Knowledgeable eyes can make sense of the many pages of the building blocks of DNA, adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C).

Each study by Malhi and his students delves deeper into an essential fact of the Americas — the impact of European colonization on the indigenous peoples who made their lives and homes, trade routes, languages, and lifestyles over thousands of years before contact from across the Atlantic. Those impacts are still playing out — in the U.S. legislature, immigration debates, and everyday lives as decisions are made about rights, resources, even reparations.

An alum of 2013 SING, Alyssa Bader is now studying with Malhi for her PhD in biological anthropology.  She analyzes how genomic information can intersect with the traditional identities and concerns of indigenous communities, an issue of personal importance due to her own Alaskan Native ancestry. The U.S. government has its own systems for identifying ancestry, using rough measures of “blood quantum” to issue the Certificates of Indian Blood that can control resources including land, housing, and education. One of Bader’s studies analyzes the ways Alaskan Natives self-identify across family oral history and legal documents and how these correlate with DNA analysis of ancestry. Inheritance is complex; the genes are passed differently from mothers and fathers, and recombinations over generations may not match personal narrative and government documents. Bader’s findings make her caution that DNA is only one aspect of what may make up someone’s “identity”.

She analyzes how genomic information can intersect with the traditional identities and concerns of indigenous communities, an issue of personal importance due to her own Alaskan Native ancestry. The U.S. government has its own systems for identifying ancestry, using rough measures of “blood quantum” to issue the Certificates of Indian Blood that can control resources including land, housing, and education. One of Bader’s studies analyzes the ways Alaskan Natives self-identify across family oral history and legal documents and how these correlate with DNA analysis of ancestry. Inheritance is complex; the genes are passed differently from mothers and fathers, and recombinations over generations may not match personal narrative and government documents. Bader’s findings make her caution that DNA is only one aspect of what may make up someone’s “identity”.

Bader’s current research probes individual experience in pre-European contact cultures along the Pacific coast from British Columbia to Peru. She uses tooth samplings and tiny flakes of dental calculus — yes, what your dentist scrapes off with those sharp little instruments — that reveal the larger context of both human DNA content and the bacteria and food particles in the mouth. She pipettes the samples through a complex protocol to extract, purify, and replicate the DNA, after donning a white containment “bunny suit” and entering the sterile basement lab of the Institute for Genomic Biology to protect against contamination by modern DNA. She is slowly building a wider picture of the individual, their ancestry, disease, diet, and more.

Dr. Malhi’s expertise in both the science of what he studies and its implications has made him a respected guide to other scientists engaged in ancient DNA research. They are developing relationships with indigenous people to include their concerns and beliefs in future research. His students are branching into their own studies that will change the conversation of what we know about the earliest Americans, and the interminglings of European and African arrivals.

Take a look on the streets of Champaign Urbana and think what the DNA of a few people passing by could tell you about the trajectory of the human spirit.

And a salute to that letter A, ancestor of them all. The early form that inverts to our Latin A is a pictogram of the head of an ox:

It is dentified as proto-Sinaitic, from the Sinai desert area around 1800 BCE. That led to the Phoenician aleph, on to the Hebrew, the Greek alpha and finally our Latin A. In lower case, you can write either a two-storey a or one.

Here’s a nod to Wikipedia for tracing the forms.

Cope Cumpston is resident book designer, typographer, and community enthusiast. The archive for Abecedarian Amble lives here.