Earlier this month, the Graduate Employees’ Organization at the University of Illinois was on strike, seeking more fair pay for the work in educating. A tentative agreement was reached and the GEO secured higher wages and better insurance coverage. Though the process was lengthy and disruptive for the instructors and students alike, Illinois graduate student educators have been successful in their efforts for a fair contract. The length of the strike reminded students of the importance of grad student educators and role of activism on the Illinois campus. The GEO’s strike is not the only demonstration that has occurred on campus, just the most lengthy and visible in recent memory; gatherings for the empowerment of students of color, Palestinian rights, LGBT+ liberation, and a plethora of other causes are commonplace at the University. Far too often, these important campus struggles are overlooked in the annals of UI history, so perhaps it is time to share a story relatively unknown outside of campus historian circles.

In the interest of full disclosure, I should note that there are very few resources available about this story. My information has come from professors and a UI oral history transcription from the late administrator Hugh Satterlee. I implore those with more knowledge of the topic to comment with any corrections.

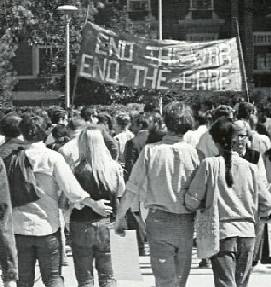

The year was roughly 1970, the Vietnam War (and associated student protests) were in full swing. The “first televised war” raised public awareness with regular broadcasts highlighting the horrors of war, which incited unrest in many activist communities around the nation, especially on college campuses. Chemical warfare, like the herbicide and defoliant “Agent Orange,” which was modeled after a compound discovered in the 1940s at the University of Illinois by Arthur Galston (who later campaigned against the use of Agent Orange), was widely deployed in the southeast Asian country, decimating foliage and disabling an estimated 1 million Vietnamese people. The loss of farmland caused widespread starvation among civilians and long-term environmental damage in one of America’s most visible examples of “collateral damage.”

The year was roughly 1970, the Vietnam War (and associated student protests) were in full swing. The “first televised war” raised public awareness with regular broadcasts highlighting the horrors of war, which incited unrest in many activist communities around the nation, especially on college campuses. Chemical warfare, like the herbicide and defoliant “Agent Orange,” which was modeled after a compound discovered in the 1940s at the University of Illinois by Arthur Galston (who later campaigned against the use of Agent Orange), was widely deployed in the southeast Asian country, decimating foliage and disabling an estimated 1 million Vietnamese people. The loss of farmland caused widespread starvation among civilians and long-term environmental damage in one of America’s most visible examples of “collateral damage.”

Research universities partnered with the military to develop chemical weapons, and UI’s chemistry program (likely enticed by military funding) was rumored to have manufactured herbicides like Agent Orange at the Noyes Laboratory. Anti-war activists were enraged by this notion and the correlation between their institution of higher learning and human suffering abroad. Students were said to have obtained some form of herbicide (perhaps Agent Orange stolen from University facilities) and were to spray it on the Morrow Plots, defacing one of the university’s most important sites, to demonstrate how Vietnam’s crop fields and food sources were being obliterated by chemical warfare. The group took the name “Morrow Plot Marauders.”

But word got out, as late Illinois faculty Hugh Satterlee recalled in the his interview. Then-chancellor Jack Peltason did not take the threat to the existence of a university landmark sitting down. He threatened the protestors, announcing that the College of Agriculture was going to bring guns to defend America’s oldest experimental agricultural field.

Eventually, the herbicide plan was dropped. Instead, a student dressed as a part-soldier, part-court jester sprayed water on the Morrow Plots to symbolize the dropping of defoliant in what may have been the Morrow Plots’ closest brush with death in its nearly 150-year history.

With the acre of corn still growing in the middle of the UI campus, this forgotten tidbit of Illinois history can give us a chance to consider the importance of space. How much value can we give a space? How much does space define us? What circumstances justify the loss or occupation of these valued spaces? Is withdrawal from weapons manufacturing reason enough to let the Morrow Plots be destroyed? Was occupying the Illini Union in the late sixties enough justification to arrest 240 Black students who were simply fighting for their right to an education?

Today, UIUC retains strong military ties. There’s no more herbicidal weaponry, rather students work to develop solutions to engineering issues alongside military personnel or enlist in ROTC. Alongside that, Illinois students have remained vocal in opposition to injustices and steadfast in fighting the good fight, in strikes, demonstrations, and walkouts.

Photos from UI archives.