How many times a day do you encounter one, without giving it a thought? Until, of course, you’re standing in a brutal February wind and just can’t get the darn thing zipped. How did this piece of ingenuity come to be, and then work its way so deep into the fabric of our daily lives? The story holds successes, failures, beauty, and wisdom, from tobacco pouches to lizard tails. And there are experts in Champaign-Urbana, happy to share their insights.

There was, first, a problem to be solved. The principles behind any invention begin with a “frame of reference,” as Industrial Design faculty Jim Kendall laid out for me. What are the time, the place, the situation, the materials and resources available? What are the expectations and habits of potential users? What are the economics of development and manufacture?

The Industrial Design studio in room 104 of the Art + Design building buzzes with just this kind of probing analysis. When I visited, the students were designing micro-kitchens for a South Korean home. Here, faculty Kendall and Deana McDonagh take a close look at early sketches.

Ask the students why they’re majoring in Industrial Design; they’re eager to tell you. They want to make the world a better place. They like intensive problem-solving, beautiful design, cool software, sustainability, and social justice. McDonagh sums it up as “joy, beauty, and function.”

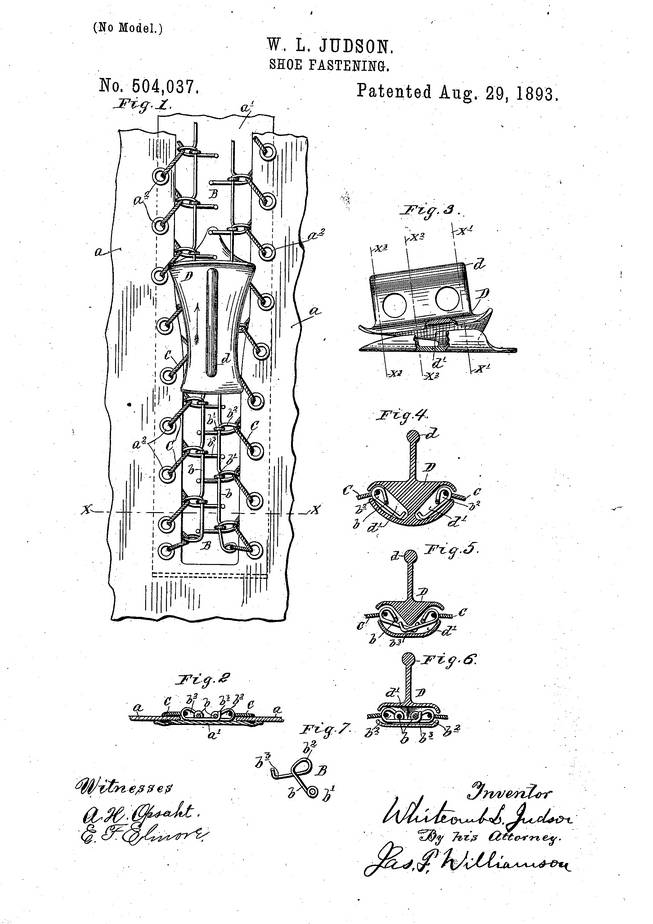

In 1890, one portly gentleman was increasingly frustrated as he bent over each morning to fasten a swath of stubborn little boot buttons. Whitson Judson knew there must be a better way. He came up with a smooth and continuous “clasp and unclasp unlocker” system, got himself a patent in 1893, set up manufacturing in Universal Fasteners Company, and even displayed the gadget at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. But it just didn’t catch on; there were issues of reliability, durability, and expense.

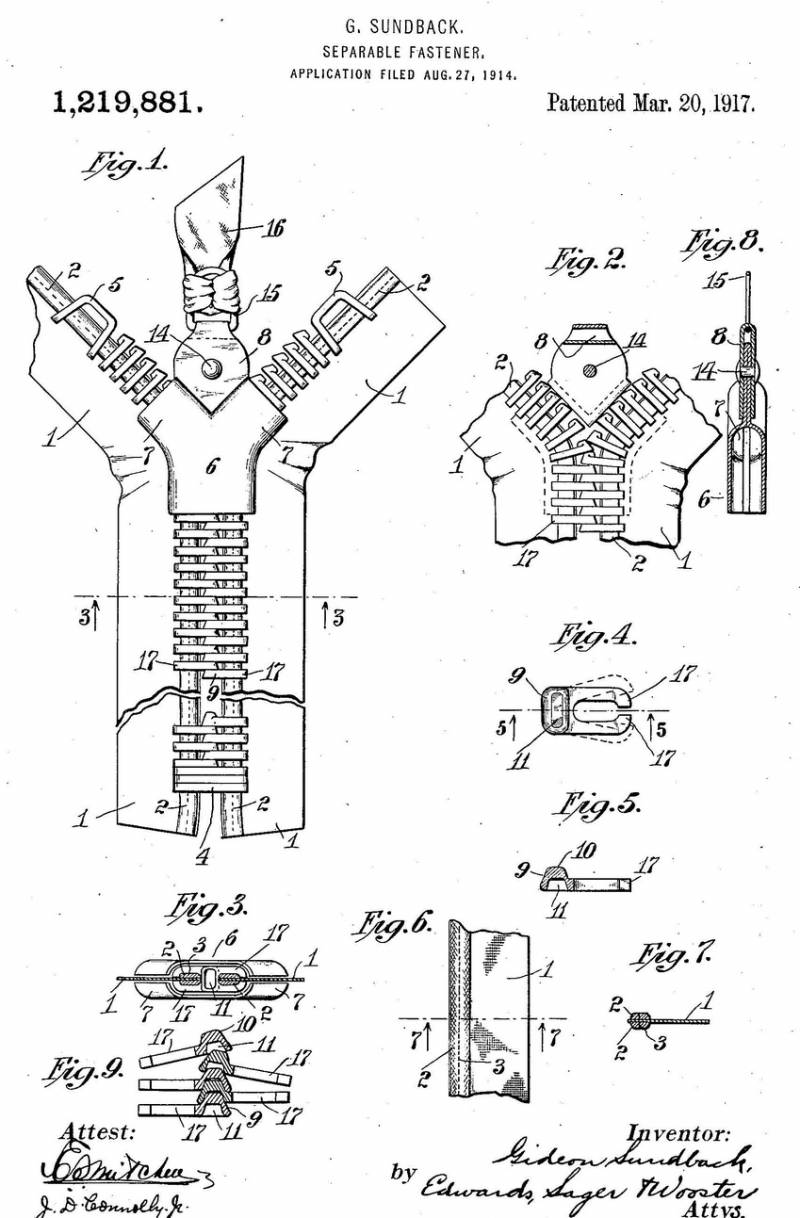

It took the careful eye of his son-in-law, Gideon Sundback, to envision a “hookless fastener,” which he patented in 1917. Rather than clothing, the first uses were sleeping bags and gear for the U.S. Army, mail bags for the Postal Service. Especially popular were tobacco pouches.

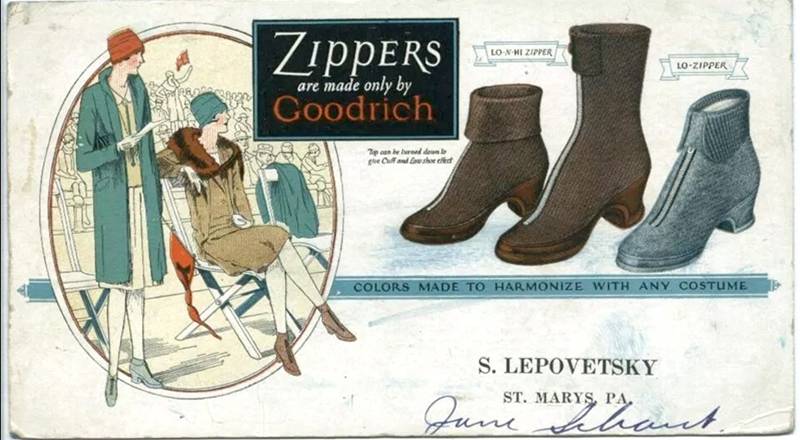

It took B. F. Goodrich to proclaim the joy of this new invention. He wanted a reliable and waterproof way to fasten rubber boots, and in 1923 bought 120,000 gizmos from Sundback. He so delighted in their sound and the speed that he dubbed them “zippers.” And that was the nickname that reeled in customers.

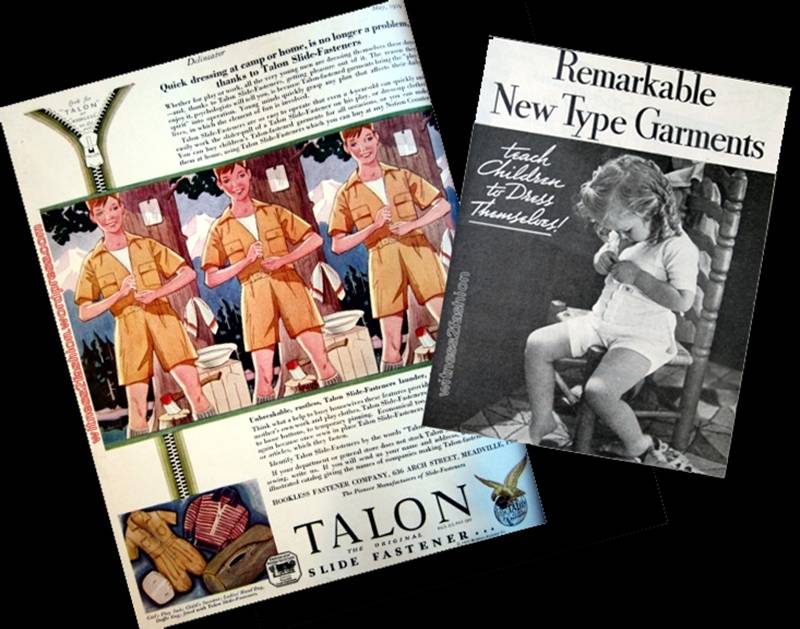

An unexpected “need” in the 1920s arose out of the growing field of child psychology. Researchers and parents were concerned that children couldn’t dress themselves with all those fiddly little buttons holding things together. They teamed up with Sundback’s company, by then called Talon, and transformed the landscape of children’s clothing.

Button-closing pants were a challenge for more than children. Designers noticed the newfangled fasteners, and staged an actual “battle of the fly” in 1937. Competing against times, the zipper won handily over buttons. Esquire made it official: the “Newest Tailoring Idea for Men” and, better yet, protection from “the possibility of unintentional and embarrassing disarray.”

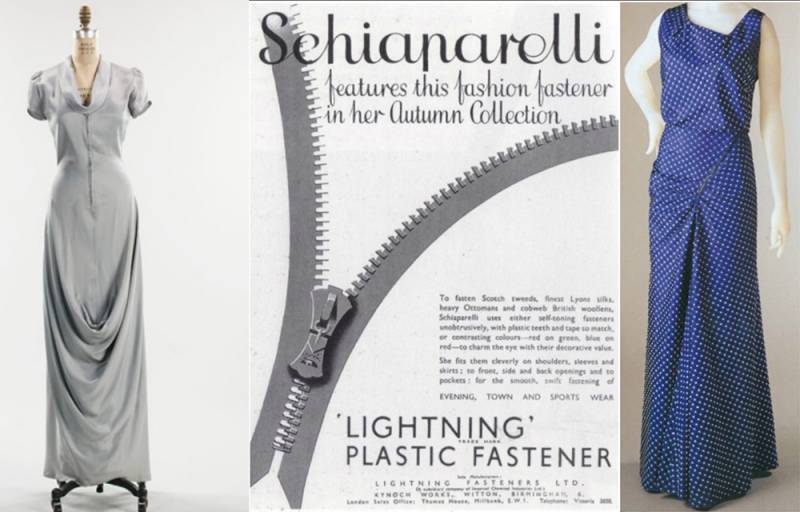

Pragmatics are one thing; pure fashion is another. French designer Elsa Schiapparelli was always intrigued with “the new.” In the 1930s she teamed up with zipper makers on both sides of the Atlantic to try out brightly colored zips in sportswear. Her 1934 line featured them oversized in unexpected places, and fashion took the plunge.  In 2010 New York designer Sebastian Errazuriz made a dress entirely of 120 zippers, and boasted that it allowed for 100 different styles.

In 2010 New York designer Sebastian Errazuriz made a dress entirely of 120 zippers, and boasted that it allowed for 100 different styles.

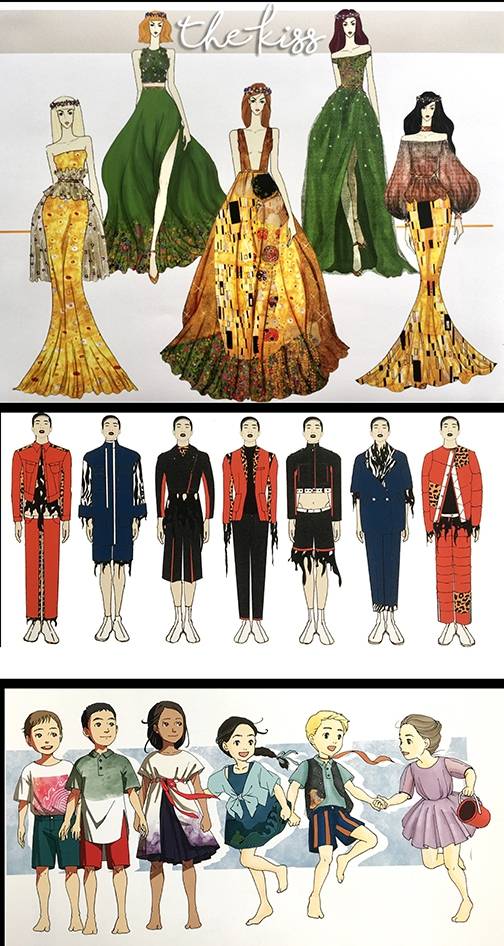

Once again in our very own Art + Design Building, students learn the art and discipline of the clothing business in Chiara Vincenzi’s fashion design class.

Beyond pretty concepts, the critical follow-up is black-and-white “flats,” line drawings that specify materials, seams, and types of closures. Zippers on the side, back, invisible or flaunted? Satin buttons for that precious evening dress?

Vincenzi earned her experience and expertise in the real world of children’s fashion at Benetton in Italy. She pointed out the design-winning “Code Prototype,” designed by Fu Zhih-Chi, where zippers allow every element from collar to sleeve to body to be deconstructed, redefined, and when necessary, replaced.  Hidden deep in the lower floors of Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, zippers really strut their stuff. The Costume Shop of the Theatre Department requires speed, skill, strength, agility, and ingenuity in craft and materials. It’s their job to transform design drawings into real clothes on real bodies for a dizzying variety of stage performances.

Hidden deep in the lower floors of Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, zippers really strut their stuff. The Costume Shop of the Theatre Department requires speed, skill, strength, agility, and ingenuity in craft and materials. It’s their job to transform design drawings into real clothes on real bodies for a dizzying variety of stage performances.

Costume Director Andrea Bouck works with a team of 17 that evaluates the two-dimensional designs on paper, and figures out how to devise, stitch, sculpt and fit them for action on stage. Rose Kaczmarowski, draper and “costume technologist,” is expert in every aspect. When given a design sketch, the first question she asks is “how do you want this to open?” “Quick changes” rule performances. It’s ideal for costumes to be historically accurate, but when Dickens wrote The Christmas Carol in 1843, he didn’t anticipate rapid costume switches. Only newfangled back zippers could make that possible.

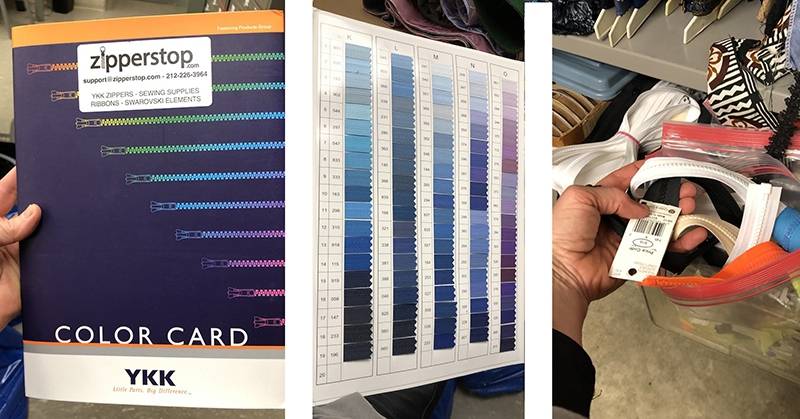

The various fasteners backstage at Krannert show every option: lace-up corsets, button fronts, zippers at every angle, hidden or exposed. Plastic toothed zippers are gentlest and most reliable, specified in gauges from #2 to #10, teeth 2-10.6 millimeters wide. Plastic coil zippers are invisible and self-healing, but too prone to pop open under stress. Metal may drape better but the teeth too easily pinch or get tangled in fabric. Velcro is too noisy. Magnets can be just the thing for instant opening.

This is also a teaching department, so students assist in every task, and study the specifics. A for-credit tailoring class is offered by Richard Gregg, recently arrived from work on Broadway shows.

Zippers can solve unusual problems. The lizard costumes created for “Seascape” highlight long tails, which get dirty after one performance dragging on the stage. How to clean them quickly and easily? Attach by zipper, and presto, remove instantly, leaving the body intact. If one sleeve of a costume suffers a gunshot, a clever zipper attachment can allow easy removal and cleaning off that bit of blood. Then there’s “fat-padding,” to bulk up characters as necessary. A tight underskin hugs the body, with layers of wadding stitched on top. Zippers provide just the right flat seams to make a smooth line under the costume, and flexibility for how many layers are needed.

Here’s the team at work — left to right Andrea Bouck, Rose Kaczmarowski, and Richard Gregg wielding some fat-padding. He also handles costume rentals.

_________________________

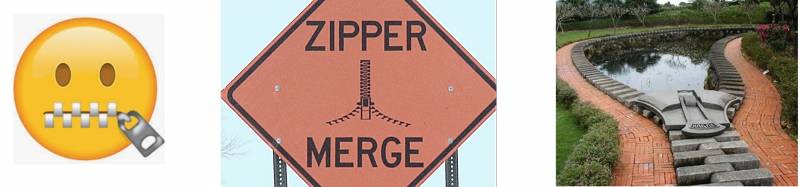

My final salute is to the Zipper as Metaphor.

They’re simply so beautiful. It’s so satisfying when that slider slides sleek and smooth, teeth feeding evenly, with a slight buzz, from two strands to one precise seam. It’s the perfect instruction for traffic merging from two lanes to one — be polite and orderly, cars weave one at a time. I thank Jun Kitagawa for the artistry that begins this article. Enjoy Ju Chun’s meditation on a lotus pond in Taipei.

The mysteries of concealing and revealing. Here’s a moment of appreciation for The Zipper.

* * *

This is an abecedarian amble, so let’s look at the letter Z, the caboose of the Latin alphabet. The original shape may derive from the Phoenician letter “zayin,” meaning ax,  dating some 3000 years. In 800 BC the Greeks named it zeta, and that led straight to our usage today.

dating some 3000 years. In 800 BC the Greeks named it zeta, and that led straight to our usage today.

* * *

Cope Cumpston is resident book designer, typographer, and community enthusiast. The archive for Abecedarian Amble lives here.