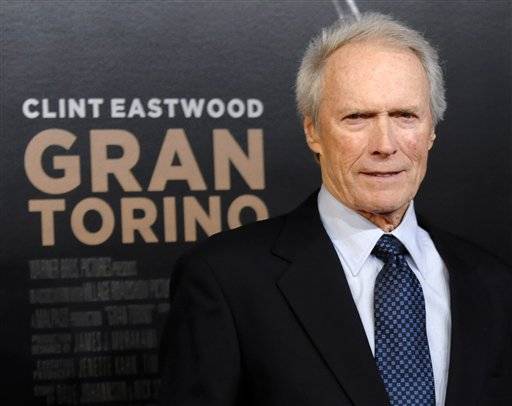

Gran Torino proves to be a requiem of sorts for Clint Eastwood. This graceful, poignant film is the perfect exit for the iconic actor/director, as he displays not only his usual confidence behind the camera but is also at the height of his skills in front of it. Never before has Eastwood given such a reflective, introspective performance. As Walt Kowalski, a bitter widower who finds himself a stranger in his own country, Eastwood portrays a man who is the only one left in a Detroit neighborhood that’s been taken over by myriad immigrant groups. Adding insult to injury is the fact that he doesn’t know how to relate to his estranged sons. The only friends he ends up having are the neighbors he initially hates the most.

Gran Torino proves to be a requiem of sorts for Clint Eastwood. This graceful, poignant film is the perfect exit for the iconic actor/director, as he displays not only his usual confidence behind the camera but is also at the height of his skills in front of it. Never before has Eastwood given such a reflective, introspective performance. As Walt Kowalski, a bitter widower who finds himself a stranger in his own country, Eastwood portrays a man who is the only one left in a Detroit neighborhood that’s been taken over by myriad immigrant groups. Adding insult to injury is the fact that he doesn’t know how to relate to his estranged sons. The only friends he ends up having are the neighbors he initially hates the most.

While the trailers for the film suggest this is Dirty Harry for the geriatric set, Torino’s strong suit is its presentation of the cross-generational relationship that develops between Walt and Thao (Bee Vang), a teenager of Hmong heritage who tries to steal the old man’s prized Gran Torino as part of a gang initiation. A bigot to the core, Walt regards the kid as just another “zipperhead,” until he realizes that the young man possesses a degree of respect and responsibility that he fails to see in his own grandchildren — or anyone else for that matter. Taking the boy under his wing, he shows him how to “man up” and take charge of his life. While the racial epitaphs Walt and the local barber teach Thao to use so he can be more manly are woefully inappropriate, the sense of dignity and confidence he develops under his tutelage proves invaluable.

One of the most interesting aspects of the film is its view of modern America. As personified by Walt’s children and grandchildren, today’s Americans are rude, insensitive and disrespectful; spoiled people who’ve never had to work hard a day in their lives, and expect to live a life of ease and happiness with minimum effort. The gang harassing Thao is viewed in the same light, shiftless young men who’ve become Americanized, opting to steal rather than work for what they want. In turning their backs on their culture, they have chosen to acclimate to their new home by taking the easy route. On the other hand, Thao and his family, as well as many other immigrants in Walt’s neighborhood, work hard, look out for one another and take pride in their heritage, qualities that the war veteran adheres to, which has made him a stranger in his own land. Walt is a man out of time and outside his own culture, yet ironically finds a home among those he initially despises.

Unfortunately, the gang rears its ugly head in the film’s third act, and Thao and his sister Sue (Ahney Her) find their lives in danger. Walt rides to the rescue and it’s to Eastwood and screenwriter Nick Schenk’s credit that the movie’s climax plays against expectations and opts for realism over wish fulfillment. It is in the film’s final moments that the actor truly shines, putting to rest old demons while preparing for one last stand. The subtext here is unmistakable and it adds to the movie’s poignancy as we become aware that Eastwood himself is putting things to rest. Cinematic history is playing out before us here, and it’s as powerful as any exit put on film.

Gran Torino’s message is a worthwhile one; it espouses the virtues of honor and dignity as well as the value of earning the respect of those who put a proper value to it. Walt puts these things above anything else. As a result, he’s lonely, because in doing so, he proves himself a dinosaur. Most who surround him cling to the superficial, opting for the easy way out in everything rather than the pride that comes from earning anything of value. It’s fitting that Eastwood be the one who delivers this message as he’s built his incomparable career by adhering to these precepts. As such, Gran Torino is one of the most genuine films of 2008 and one whose message will far outlive the messages of the many vacuous movies that will come in its wake.