Once upon a time, movies were colored with a black-and-white palette of irony, cynicism, imagination, and wit. They were the stuff that dreams were made on, as Prospero put it.

Once upon a time, movies were colored with a black-and-white palette of irony, cynicism, imagination, and wit. They were the stuff that dreams were made on, as Prospero put it.

And in this Ancient World, there were a people known as the Projectionists, now nigh extinct, who labored in the dark, carrying spools of magic mile-long ribbons, waiting attentively upon machines that ratcheted noisily in muffling boxes to oversee the mesmerism of the Willing Suspenders.

The Willing Suspenders? Sounds like an Amish punk band.

Ah, those were the days. I was a projectionist at Latzer Hall at the campus YMCA in the 1970s, a member of the Expanded Cinema Group, a job I thought would last forever. Every weekend I sat in the meeting room behind the projectors, ordering Papa Del’s or Chinese Garden shrimp with lobster sauce or Bubby and Zadie’s sprouts-laden sandwiches.

I knew exactly when to get up for the reel changes, because week after week, semester after semester, we showed the same movies: the movies people wanted to watch. And I watched them too, over and over, three shows a night, three nights a week.

I’d see the backs of the heads of the crowd as they responded in unison. We’d show Halloween and the audience would jump out their seats, right on cue.

I’d see the backs of the heads of the crowd as they responded in unison. We’d show Halloween and the audience would jump out their seats, right on cue.

I used to invite friends. “Here it comes,” I’d say. The masked Michael Myers would jump out unexpectedly, the crowd would levitate a few inches and scream, and my friends and I would spit out pieces of pizza laughing.

The snappy punch lines in Woody Allen’s Sleeper or the famous heart-tugging lines from Casablanca, we saw them all coming and still we responded, even those of us with pizza in our mouths, again and again, a collective experience.

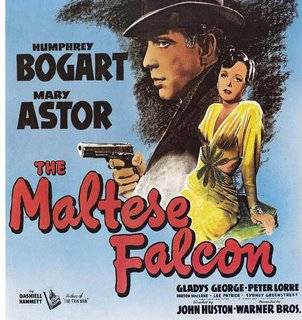

The Maltese Falcon was also one of those never-fail perennials, flowering semester after semester, always bringing a crowd to watch Humphrey Bogart, whose picture in those days adorned dormitory walls, back when smoking was still bad-boy glamorous.

When Mary Astor declares her love for Bogart, after all the bodies and lies are piled up, the Latzer Hall audience issued a kind of collective verbal sneer, at the conniving, the calculation, the web of deception that at some point everyone fell game to, the characters on the screen as well as those willing suspenders in the audience.

When Mary Astor declares her love for Bogart, after all the bodies and lies are piled up, the Latzer Hall audience issued a kind of collective verbal sneer, at the conniving, the calculation, the web of deception that at some point everyone fell game to, the characters on the screen as well as those willing suspenders in the audience.

Now the whole population of the Twin Cities has a chance to relive that collective experience. Throughout the month of April, the Champaign and Urbana libraries and the National Endowment for the Arts are sponsoring The Big Read, using Dashiell Hammett’s 1929 classic novel.

We can’t regain our naiveté. Bogart or The Maltese Falcon may have presaged the ironic cynicism of the 21st century, but there is something about the entire genre of film noir that nudges us back into a state of being, once again, willing suspenders of disbelief.

Whatever else film noir is — and there will be a chance to explore those ideas all month — it’s about attitu de. People have pointed to John Huston’s 1941 film version of The Maltese Falcon as the first, best example of film noir, and the film will be projected for free at the Virginia Theatre on April 30.

de. People have pointed to John Huston’s 1941 film version of The Maltese Falcon as the first, best example of film noir, and the film will be projected for free at the Virginia Theatre on April 30.

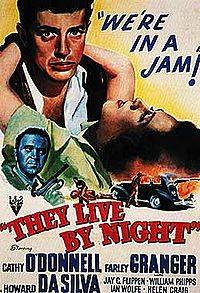

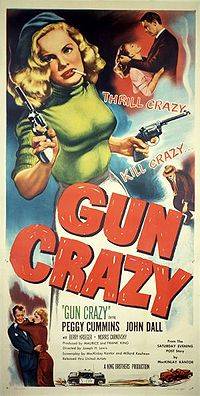

Four other classic film noirs will be shown at the Champaign or Urbana libraries on successive Wednesdays at 7:00 p.m. throughout April, starting with Murder My Sweet (1944), the adapted Raymond Chandler novel starring former song-and-dance man Dick Powell. They Live by Night (1948) reflects Depression-era desperation; let’s hope it’s not too relevant today. Gun Crazy (1949), well titled, reflects an all-American attitude toward firearms ingrained from childhood. And Robert Aldrich’s far-out Kiss Me Deadly (1955) incorporates the atom bomb fears of the Fifties into a careening, screeching noir mode.

What is film noir? For one thing, I always think of visual style. Venetian blinds and cross-hatched shadow stripes. The ceiling is in the shot because the camera is aimed up from knee level. Or aimed down from behind the ceiling fan.

I think of people deceived by each other and by themselves. J.J. Gittes (Jack Nicholsen) in Chinatown (1974) — the first really great film noir in color — thinks he is as cool and clever as Bogart, but he never really knows what is going on. He has it wrong from square one.

I think of people deceived by each other and by themselves. J.J. Gittes (Jack Nicholsen) in Chinatown (1974) — the first really great film noir in color — thinks he is as cool and clever as Bogart, but he never really knows what is going on. He has it wrong from square one.

I think of convoluted narratives that one need not figure out entirely. Famously, at least one of the dead bodies in The Big Sleep (1946) is left unexplained by the film’s end.

Duplicity, the movie still in the theaters today, is not exactly noir, but Julia Roberts and Clive Owen owe a great deal to Bogart and Astor. Things aren’t what they seem in this convoluted story and you certainly don’t know whom to trust, if anyone.

The romance that may not be a romance at all is indebted to The Maltese Falcon and to the genre that put cynicism on the map.

Now all I have to do is read the book, because it all starts with the writing.