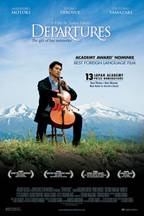

I was incredibly lucky this Ebertfest. According to two different Smile Politely articles, coverage of Day 2 and coverage of Day 3, I was fortunate enough to experience the “finds of the festival” by seeing and reviewing Munyurangabo and now, Departures, which won the Oscar for best foreign film in 2009.

I was incredibly lucky this Ebertfest. According to two different Smile Politely articles, coverage of Day 2 and coverage of Day 3, I was fortunate enough to experience the “finds of the festival” by seeing and reviewing Munyurangabo and now, Departures, which won the Oscar for best foreign film in 2009.

As I’ve already said, Munyurangabo is fantastic. An incredible view of Rwanda and the tension for the cycle of children, now coming of age and having to deal with the consequences of what their parents left them, it is a must-see.

However, Departures truly blew me away in a different way, in that it strives for appealing to the universal feelings towards death by humanity, rather than directing its perspective towards a specific culture.

This Japanese film, directed by Yojiro Takita in 2008, begins with a thick, misty view of a road. Because I knew the film is about death, I immediately feared some surreal, hard-to-understand drama, which would leave me depressed at the end.

However, the misty drive quickly leads to an easy-to-sympathize with story about Daigo Kobayashi, a man who followed his dream to be a cellist, then finds that fate has something else in store for him as a worker in “encoffinment,” a process that brings closure to the families of the deceased through preparing the body for being placed in the coffin, and later cremated.

Before the movie started, it was introduced by the panelist, Professor David Bordwell, and he said in his introduction that this is a “very Japanese movie,” meaning that it is about unabashed emotion, and keeps in the tradition of frank sentimentality in the Japanese cinema.

This film is about death, he said, but also about plants, stones, birds, and a lot about food.

And he is right. This movie takes a concept that we are afraid of ― death ― and views it through the eyes of humans in their day-to-day lives, who are constantly forced to confront the fleeting aspect of mortality, and yet from there, appreciate the dignity and joys of human life all the more.

And he is right. This movie takes a concept that we are afraid of ― death ― and views it through the eyes of humans in their day-to-day lives, who are constantly forced to confront the fleeting aspect of mortality, and yet from there, appreciate the dignity and joys of human life all the more.

I will not go more into the synopsis (as with many things, the beauty of this story is in the viewing) except to say that the characters are sympathetic and understandable, and their fears and joy are easily shared by the viewers, who reacted many times throughout the movie with gasps, laughter or sighs.

Professor Bordwell described the movie as a “wet” movie, a concept in Japan that refers to a movie that induces much emotion, including laughter and tears. That is most definitely true of this movie.

After the film, the director spoke through a translator about the movie and the making of it. He worked in the role of encoffinment, to get a better experience for the part. After he learned how passionate the people in that professional role were for their occupation, he felt even more inclined toward making the movie, though he thought it would not be successful, due to there not being enough interest generated towards the movie.

After the film, the director spoke through a translator about the movie and the making of it. He worked in the role of encoffinment, to get a better experience for the part. After he learned how passionate the people in that professional role were for their occupation, he felt even more inclined toward making the movie, though he thought it would not be successful, due to there not being enough interest generated towards the movie.

A point mentioned by one of the panelists was that with death being such a taboo subject in the Japanese culture, it was a terrible irony for the performer of the “encoffinment” to be so ostracized. While the director agreed, he argued that every culture, including ours, tries to ignore death. The fact that it is such a universal issue is what makes this movie such a moving piece on humanity. The director, as Bordwell states in the introduction, treats the subject with a “gentle respect” that makes this movie well worth watching and enjoying. As Jamie Newell says in her article, “Just move mountains to find a copy of it and watch it for yourself if you haven’t had the pleasure.”