There are many interesting things about Mark Twain that are generally known, and there are many interesting things about him that aren’t. To learn more about the latter, visit the current University of Illinois exhibit at The Rare Book & Manuscript Library, “Mark Twain: Mysterious Stranger.” The exhibit is running currently and ends June 29th. It features seven cases of carefully selected items pertaining to Twain, all from the UI’s collections, including, as it says in the 1880s-style exhibit brochure, “Rare Editions, Photographs, Unique Ephemera, Inventions, etc. etc.” Twain died on April 21st, 1910, a century ago, and the exhibit was assembled to honor him on this anniversary.

There are many interesting things about Mark Twain that are generally known, and there are many interesting things about him that aren’t. To learn more about the latter, visit the current University of Illinois exhibit at The Rare Book & Manuscript Library, “Mark Twain: Mysterious Stranger.” The exhibit is running currently and ends June 29th. It features seven cases of carefully selected items pertaining to Twain, all from the UI’s collections, including, as it says in the 1880s-style exhibit brochure, “Rare Editions, Photographs, Unique Ephemera, Inventions, etc. etc.” Twain died on April 21st, 1910, a century ago, and the exhibit was assembled to honor him on this anniversary.

Subscription sales and money

In the exhibit are two American first editions from the 1800s of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer sold by subscription. As the exhibit literature explains, selling books by subscription was an emergent form of publishing marketing where salespeople went out on the railroads and peddled books directly to the masses. This was considered a lowbrow way of moving product by more refined and traditional publishers, authors and readers, and subscription books tended to have more gaudy covers and packaging that reflected the lower socioeconomics of their intended audience.

Twain, although now considered a dignified Great American Novelist, sold a lot of books through this brash new subscription method (although he also released books with more reputable publishers as well). But then, he didn’t get into writing in the first place for entirely artistic reasons. Jennifer Lieberman, UI English graduate student and one of the curators of the exhibit, explained, “A lot of the time Twain was writing for money. His first journalism exploits were for fun, and then he realized he had a talent for it. Definitely after 1890, after A Connecticut Yankee, he owed publishers money and they made him work for it.”

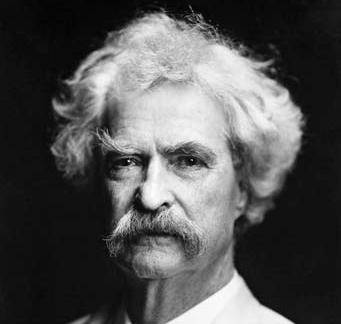

Twain’s relationship with money was a complicated one. Raised in Hannibal, Missouri, he began working as a printers’ apprentice at the age of 12 and wasn’t surrounded by wealth and glamour as a youth, although his childhood was more like Tom Sawyer’s than Huckleberry Finn’s. Later in life, after he became a celebrity author and personality, he rubbed elbows with some of the wealthiest people of the late 1800s, including Standard Oil businessman Henry Huttleson Rogers, who gave Twain financial counseling when Twain was in dire straits. However, unlike some of the tycoons he socialized with, because Twain had lived in more reduced circumstances, he wasn’t always comfortable with the opulence he witnessed.

Lieberman said, “The times he went bankrupt he was bailed out by friends in high places and he could legitimately like these people as friends, but really despise the kind of corporations they got their money from. And I think that’s where the tension between his attraction to wealth and to populism comes from, too. He remembers being buddies with average folk in Nevada and San Francisco and then he had these friends who represent their exploitation.”

So did any of the tacky subscription sales come back to haunt him when he reached old age, the time when many artists start to think about their legacy? “No,” Lieberman answered.

Holographs, houses and insecurity

Holographs, houses and insecurity

One exhibit item is a handwritten letter Twain sent to his friend and editor William Dean Howells. In the letter, Twain has some scathing things to say about the prose of Jane Austen: “Jane is entirely impossible. It seems a great pity that they allowed her to die a natural death.” In the same letter, Twain also describes Edgar Allan Poe’s work as “unreadable.”

Why such bile? Or is Twain just trying to be funny? Another of the exhibit curators, UI English graduate student Kerstin Rudolph elaborated: “In this letter he’s poking fun at Jane Austen and Edgar Allen Poe, but also behind this humor he’s trying to show himself as a serious author himself. I think it also shows some insecurity about his own legacy and how he’d like to be seen.”

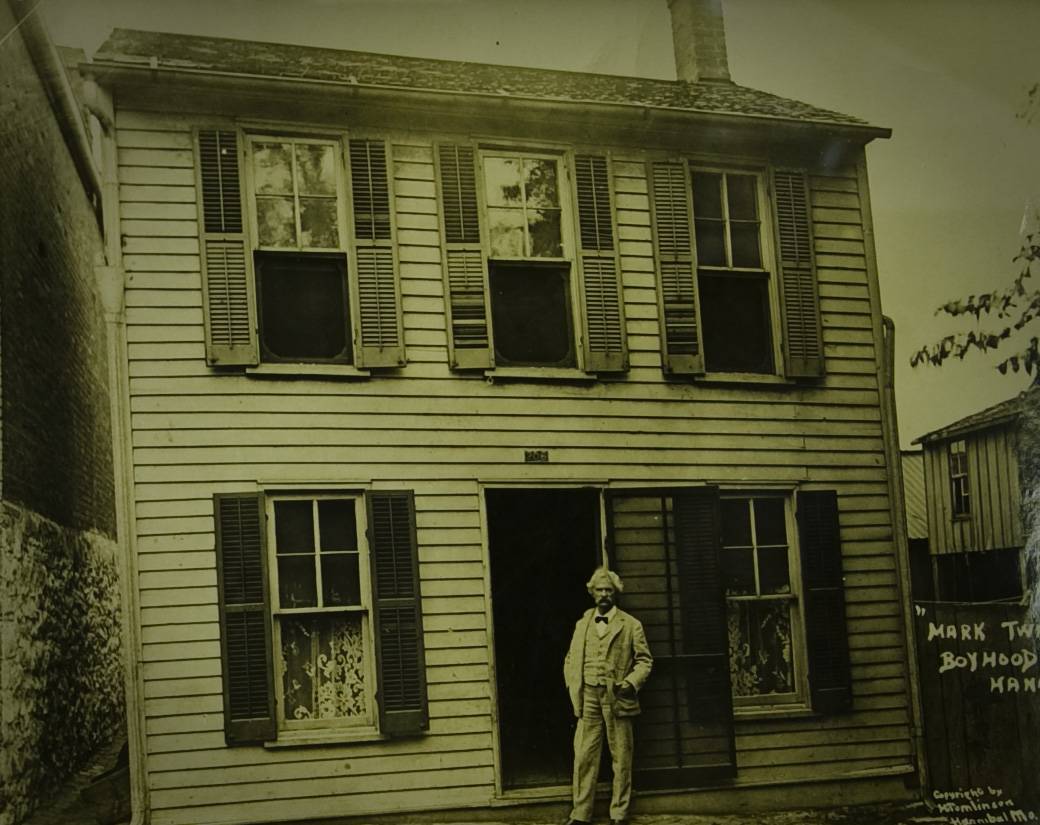

In the exhibit are photographs of different residences Twain lived in over the years. One picture shows Twain as a famous adult posing next to his modest boyhood home in Hannibal (see picture). Another shows the elaborate house he built in Hartford, Connecticut in 1874.

When he built the Connecticut house, Twain was a national celebrity married into an established and wealthy New England family. He was trying to project an image of success in the structure, even as he struggled financially himself. Basically, Twain was trying to fit in. According to Rudolph, some of what drove Twain to build such a house was an effort to be taken seriously and welcomed socially by the east coast literary and cultural establishment: “Here’s this guy from the West—he has the most opulent house on the street. You might want to go to his parties, but are you really going to accept him?”

In 1874, Missouri, where Twain grew up, was still considered the “West.”

Mark Twain, Jon Stewart, and wacky inventions

Another exhibit item is an essay Twain wrote as a celebrity later in life called “Mark Twain As Reporter.” In it, he reflects back on his younger days as a reporter and on the craft of journalism in general. He makes some serious statements—one of which is that he left journalism partially because his editors were requiring him to stretch the truth —but mixes his lofty musings with comic comparisons of himself to George Washington.

Why the mix of earnestness and comedy? Why didn’t he pick one or the other? Lieberman responded with a modern reference: “In his notebooks and journals, Twain writes about how satire is the only patriotic form of writing, because you need to talk about serious things, but no one will listen to you unless you are doing it with humor. And so it lets him approach issues this way that other people were approaching on a soapbox. Kind of the like The Daily Show today. I could write a whole book about how Jon Stewart is today’s Mark Twain.”

Twain was an inventor, and some of his inventions are featured in the exhibit. One—which actually earned Twain a substantial amount of money—is a “Self-Pasting Scrapbook” that Twain took out a patent on. It was a practical invention marketed under his celebrity name.

Another invention featured in the exhibit is “Mark Twain’s Memory-Builder: A Game for Acquiring and Retaining All Sorts of Facts and Dates.” This particular invention wasn’t quite so lucrative for Twain after it came out in 1885. After hearing Rudolph describe the game in 2010, it’s not hard to see why: “Looking at it, we were trying to figure out how to play it and we were like, ‘Oh my God, who would be smart enough to play this?'”

The history game reflects a man who, despite tremendous and well-documented achievements, didn’t always succeed at everything, whether it be some of the plays he wrote or some of the dinner speeches he made.

But according to exhibit curator and UI Library Science graduate student Michael Greenlee, what really “came back to haunt Twain was his books getting pirated and reprinted without his permission.” This was pretty much because he lost money on such publications.

“Posthumous imprints”

“Posthumous imprints”

Many of the exhibit items display the humorous side of Twain that is generally associated with him today. For instance, one item is a postcard from 1897 with an inscription from Twain reflecting that, “The only way to keep your health is to eat what you don’t want.”

But there’s a sadness to some of the exhibit as well. Twain had his demons, which became even worse in his final years. Greenlee said, “He did have a dark period at the end of his life that most people don’t associate with him.”

The final exhibit case features a bronze casting of Twain’s right hand made in 1908 (see picture), two years before he died. It’s a striking piece, and a dark one to close an exhibit celebrating a man we generally associate with lighthearted (yet philosophical) yarns like the one about how Tom Sawyer managed to get his fence-painting chore completed. Another somber item in this last display case is a 1916 edition of a novel that Twain never entirely finished. The book is called The Mysterious Stranger, and is about Satan visiting earth. The published version was cobbled together from drafts after Twain’s death.

Lieberman explained: “We were just thinking about the posthumous imprints that he left. We considered other things for that case, like the American Association of Arts eulogy of Twain, but we decided to leave it sparse with this bronze plate of his hand and this book that was published posthumously. We don’t actually know what motivated him to have this casting done of his hand.”

She continued, “Depression was something he battled with his whole life. Basically, if anyone he knew ever died, he could find a way to feel guilty for it. He carried guilt for the death of a prisoner he loaned a match to as a boy, for the death of his brother Henry, for his son, who he took in a carriage without a blanket, and so forth.”

Maybe you should see it

As exhibit curator and UI librarian Chatham Ewing pointed out, Twain wrote for everyday people and this exhibit is in that tradition. Pretty much anyone can get something out of visiting it—whether they know a little or a lot about Twain. And the price is right; it’s free. Also, you don’t exactly have to light out for the territory to see it—just head over to campus, 8:30 am to 5:00 pm, Monday through Friday.