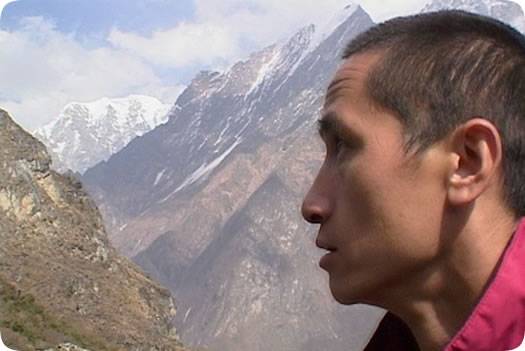

The University’s Asian Film Festival kicked off on Tuesday with Unmistaken Child, a 2008 documentary by Israeli filmmaker Nati Baratz. The film follows Tenzin Zopa, a young Buddhist monk, as he searches the Tsum valley in Tibet and Nepal for the reincarnation of his recently deceased teacher, Geshe Lama Konchog.

Diviners decide that the lama’s reincarnation is likely to be in the form of a one-year-old boy, the titular unmistaken child. Tenzin is understandably uneasy about tackling his quest, especially when he is told that a disciple who lacks merit might easily come back with a “mistaken one.”

In fact, the film is just as much concerned with Tenzin’s confusion and uncertainty as it is with the search for the new lama. Tenzin is told on several occasions the he has neither the ability nor the authority to determine whether a specific child might, in fact, be his master’s reincarnation. “I’m not Buddha,” Tenzin tells the camera, “Only Buddhas know within Buddhas.” Tenzin demonstrates unwavering faith, but is fully aware of the impossibility of his mission.

While Western audiences might expect a film about journeying across the countryside in search of a reincarnated Buddhist lama to be mystical and epic in scope, the film shines most in its depiction of mundane encounters. Much of the film is dedicated to following Tenzin as he walks from village to village and tests children for lama-like qualities. We get a sense that a roaming monk is relatively ordinary for these communities, and they are accordingly hospitable to Tenzin. This isn’t to say that the film is immediately relatable; modern technology like televisions and helicopters seem anachronistic and even jarring in the context of the stone houses and subsistence farms that Tenzin visits.

Once Tenzin finds a suitable candidate, Unmistaken Child takes a different turn as the boy is judged by the lamas of Tenzin’s monastery, as well as the Dalai Lama himself. The boy’s parents are ambivalent about the fuss over their son. They are happy to know that, should he be deemed to be the reincarnation of Lama Konchog, he will enjoy a more upwardly mobile and healthier life. However, they are also aware that they would be expected to permanently give him up to Tenzin’s monastery.

While the film does not directly comment on these difficult issues, it frames them for our consideration. As the boy wails when Tenzin attempts to give him the traditional shaved head of a Buddhist monk in preparation for his meeting with the Dalai Lama, we are given closeups of his eyes and cheeks, wet from tears. Likewise, the camera occasionally cuts away from the child’s spiritual testing to his parents, sporting furrowed brows and looking noticeably worried.

Ultimately, Unmistaken Child is the story of people reconciling internal differences. Tenzin must remain faithful while coming to terms with his own self-doubt; the boy’s parents must mitigate their joy with the fear that they will never see their son again; we, the audience, must deal with concepts of faith, freedom, and love that may be quite unfamiliar to us.