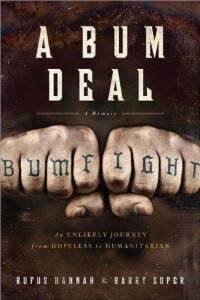

A memoir called A Bum Deal, by Rufus Hannah and Barry M. Soper, was published recently. Hannah was one of the participants in the popular and controversial Bumfights videos, a series of DVDs filmed over several years starting around 2000. The Bumfights videos, along with the criminal trials of their filmmakers, became national news in 2002 and 2003, and Ed Bradley covered the story on Sixty Minutes shortly before he died in 2006.

A memoir called A Bum Deal, by Rufus Hannah and Barry M. Soper, was published recently. Hannah was one of the participants in the popular and controversial Bumfights videos, a series of DVDs filmed over several years starting around 2000. The Bumfights videos, along with the criminal trials of their filmmakers, became national news in 2002 and 2003, and Ed Bradley covered the story on Sixty Minutes shortly before he died in 2006.

The videos show Hannah and his best friend Donnie Brennan — both of whom were homeless alcoholics at the time — fighting each other for beer money, participating in highly dangerous “stunts,” and doing plenty of other extreme stuff. In his memoir, Hannah describes the series of failures in his early life that led him to becoming homeless, how he got involved in the Bumfights videos, the unwanted fame they brought him, and, finally, how he sobered up and become an activist for homelessness issues.

A summary of events

In the late 1990s, Rufus Hannah and Donnie Brennan were homeless and living behind a grocery store in the San Diego suburb of La Mesa. Both were middle-aged hardcore alcoholics and had been on the streets for years. Ryan McPherson, a local teenage skateboarder who liked to film random stuff that he saw around town, got to know Brennan and Hannah because they all hung around the same park. Brennan, when drunk, liked to clown around for the camera. One night, he raced around the park stumbling over stuff and McPherson filmed it all. From there, McPherson began to pay the two homeless men small amounts of money — a few dollars per scene — to do increasingly dangerous stunts.

While being filmed, Hannah and Brennan careened down hills in shopping carts and on skateboards and leaped off of buildings into dumpsters. Arguably the most dangerous stunt Hannah performed on camera was very simple: he sprinted headfirst into a wall. This particular act eventually led to him having seizures, as well as vision and equilibrium issues. Hannah’s actions in the videos earned him the nickname “Rufus the Stunt Bum.”

Also, the filmmakers paid the two men to fight each other — really fight. In one brawl, Hannah broke his best friend’s ankle. As the filming continued, humiliation became more of a theme. For instance, the filmmakers paid Brennan $200.00 to have the word “BUMFIGHTS” and a picture of a bottle of beer tattooed on his forehead. Brennan, unsurprisingly, was highly intoxicated when he agreed to this.

The Bumfights videos were sold on the Internet for around $20.00 each, and hundreds of thousands were sold around the world. Later, McPherson and the other filmmakers sold the rights for the films for one and a half million dollars.

When the videos began to attract attention from law enforcement in La Mesa, McPherson moved the filming to Las Vegas, luring Hannah and Brennan there — as always — with promises of plenty of booze and riches from DVD sales, but coming through only with the booze. In Las Vegas, McPherson installed the two homeless men in an apartment, where they generally drank and watched television during the day and participated in filming at night. In Las Vegas, the emphasis of the filming shifted from extreme (beyond Jackass extreme) stunts to scenes meant to humiliate Hannah and Brennan. McPherson had Brennan whipped across his genitals by a prostitute, got the two homeless men colossally drunk and filmed them walking around an amusement park full of children with dildos strapped to their foreheads, and so forth.

McPherson, unapologetically defending these types of activities in court later on, pointed out that Brennan and Hannah both signed releases and were free to leave at any time. Hannah’s perception of his time in Las Vegas is different. He writes that — while he finally understood that McPherson wasn’t going to give him any of the real money from the DVD series and that he was just being used — he and Brennan felt stranded. He also writes that the filmmakers hired a guard to monitor them at their apartment: “But with no money or transportation, and James watching us like a hawk, we didn’t know how to get out of an increasingly bad situation.”

Finally, the two homeless men called a friend in La Mesa, businessman Barry M. Soper, who came to Las Vegas and paid for them to take a bus back to California.

McPherson — along with the other Bumfights filmmakers — was put on trial in 2003 on a number of criminal charges related to the videos. McPherson was convicted on only one charge: conspiracy to stage an illegal fight, and got community service hours. He was ordered by the judge to do his volunteer hours at a homeless shelter. When he didn’t follow through, he was sentenced to 180 days in jail.

In the meantime, things brightened up for Hannah, who stopped drinking in 2002. He started working as a property manager in an apartment complex owned by Soper, the businessman who helped Hannah get away from the Bumfights filmmakers. Soper is the co-author of A Bum Deal, as well. Hannah and Brennan also sued the filmmakers for damages and won an undisclosed amount of money.

Why would someone run headfirst into a wall for a few dollars?

One of the reasons that filmmaker McPherson only got a lone criminal conviction for Bumfights was that Hannah and Brennan participated willingly. The videos were appalling to a lot of people — including the authorities who brought the filmmakers up on charges — but it was hard to find anything illegal being done. Basically, it was all consenting adults.

In his memoir, Hannah doesn’t portray himself as a victim of the filmmakers, or blame anyone but himself for the many bad things that he describes happening throughout his life. He admits that — at least initially — he liked the attention that the filming brought him. Trying to explain why he agreed to do a stunt for McPherson that got him knocked unconscious, Hannah quotes himself saying at the time: “Because I was drunk, I got a cheering section, and suddenly I felt important.”

However, as the filming went on, Hannah writes that he participated in the videos mainly to ward off the shock of alcohol withdrawal. And he was unwilling at the time to try and stop drinking by entering a detox program (which he eventually did, through the VA). He writes:

But I had hit rock bottom when it came to my mental state and my desperate need for alcohol to keep my body functioning. Booze had become so important to my body that basically all I could think about from the time I woke up to the time I went to bed was how important it was to find that next drink. I knew shit like that would sound like a weak excuse to the average person, but unless they had been through it, there’s no way they could know what it was like going cold turkey from something that was as vital to my bloodstream as the blood itself.

A link between Bumfights and violence towards people who are homeless?

People who are homeless have traditionally been targets for assault. After the Bumfights videos became popular, some sociologists, homeless advocacy groups, and journalists began to allege that the DVDs were inspiring a new wave of violence towards the homeless. From a 2006 New York Times article about the Bumfights videos, concerning attacks possibly inspired by them:

According to law-enforcement officials, a number of young people have videotaped themselves attacking homeless people, including four teenagers in Melbourne, Australia, who killed a man by setting fire to his tent; five in Alberta, Canada, who assaulted a homeless man with bottles and a club, then urinated on his face; and four young men near Cleveland, who crept up on homeless people and shocked them with a stun gun.

The 2004 documentary film Bumfights: A Video Too Far, makes a case for a connection as well.

I wondered about assaults to people who are homeless locally — inspired by Bumfights or otherwise — so I emailed Jason Greenly, who supervises TIMES Center in Champaign. I asked him — based on his experiences working at TIMES Center — how safe he thinks homeless people are on the streets of Champaign-Urbana. I also asked him, in general, where threats to their physical safety come from. He responded:

Assaults on our residents while they’re residents are rare, and often are not related to them being homeless. (If anything, the ones we see are in retaliation for some offense — real or imagined — that the victim did toward the assailant). Assaults prior to their residency, I don’t really ever hear about.

As far as where the ‘threats to physical safety’ come from, again, I can’t speak as any sort of expert, but my observation is simply that people get assaulted for money, which is then used by the assailant to feed some sort of addiction.

He also wrote that he had never heard of the Bumfights videos.

My own reactions

I had never heard of the Bumfights videos either until recently, when I found A Bum Deal in the new books section of the Champaign Public library. When I watched the parts of the Bumfights videos I found free online (I wasn’t about to pay money to see them) years after they came out, I was — what’s the right adjective here? Shocked? Definitely. Even shock jock Howard Stern said he was shocked by them. Sickened? Absolutely. Writing about these videos — relating scenes of people pulling out their teeth with pliers and so on — doesn’t really give an accurate sense of how messed up they are. You have to see them.

Yet while I was shocked and sickened, it was a fascinated kind of shocked and sickened. I wasn’t able to actually get through the parts of the videos I found online. I’m too, what… squeamish? sensitive? I don’t know, but I did scour the Internet looking for all the information I could find about the whole subject. Although I couldn’t look directly at the videos, I couldn’t entirely look away either. Probably the best way to describe my reaction to what I saw of the Bumfights videos themselves is that they stayed in my head. So that’s a warning — they might stay in your head too, in a way you don’t want.

An online chat thread about the Bumfights videos suggests various, just punishments for the filmmakers. In my opinion, the most poetic idea came from a person who wrote something to the effect that a good punishment for the filmmakers would be for them to, one day, comprehend what they had actually done.

On the other hand, hundreds of thousands of people paid for and enjoyed the Bumfights videos. I found plenty of other comments online from people who felt that they were great entertainment.

As for Hannah’s memoir itself, it is riveting and — at the end of the day — really a book more about redemption and hope than anything else, although it certainly doesn’t begin that way. Early in the book, Hannah recalls an event from his childhood where his father kills a neighbor’s son in a hunting accident, sending the father into a permanent depression and casting a pall on the whole family. Hannah writes, “That day, the sunny side of my life started to slowly go dark.”

From there, the reader follows Hannah’s life as it steadily and increasingly darkens through ruined marriages, lost jobs, hardcore drinking, and — finally — unwanted fame from the Bumfights videos. But after Hannah puts down the bottle in his late 40s, we start to see the sun again. Hannah holds down a job, connects with estranged family members, and speaks to high school students and politicians about homelessness issues. And so on.

On the back cover of the book, there’s a before picture of Hannah during his Bumfights phase — he’s wild-eyed, drunk out of his mind, and screaming at the camera. Next to it there’s an after picture where he’s composed, sober, and generally looks like a nice, stable guy. The first picture is a perfect image of the ugliness of humanity, the second astonishing in its contrast to the first. The before picture makes a stronger impression — there’s no denying it — but I think what makes the book ultimately inspiring is that the after picture goes a long way towards erasing that impression.