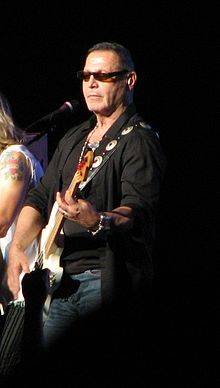

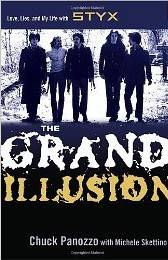

Styx is performing at Assembly Hall tonight, so it’s a good time to take a look at the autobiography of one of its founding members, bass player Chuck Panozzo. The book is called The Grand Illusion, Love, Lies, and My Life with Styx and was published in 2007. As you’d expect, there is plenty about the band itself, but Panozzo, who is gay, actually focuses more on his own journey from being confused by ― and also hiding ― his sexual orientation in his youth to becoming an activist for gay causes today.

Styx is performing at Assembly Hall tonight, so it’s a good time to take a look at the autobiography of one of its founding members, bass player Chuck Panozzo. The book is called The Grand Illusion, Love, Lies, and My Life with Styx and was published in 2007. As you’d expect, there is plenty about the band itself, but Panozzo, who is gay, actually focuses more on his own journey from being confused by ― and also hiding ― his sexual orientation in his youth to becoming an activist for gay causes today.

Panozzo was born in 1948 and grew up in an ethnic Italian neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. He formed the band that would eventually become Styx with his twin brother John when he was twelve. Keyboardist Dennis DeYoung joined a few years later, and the band went on to fame and fortune in the ‘70s and ‘80s, until breaking up in 1984. Styx reformed in 1990, although DeYoung ― who wrote many of the old hits ― is no longer involved.

Panozzo was diagnosed with HIV in 1991, but didn’t tell the rest of the band until he was diagnosed with AIDS in 1998 and he couldn’t hide it anymore. He still tours with Styx when his health allows him to, and writes, “I now spend a lot of my time speaking out on human rights and HIV/AIDS awareness.”

Panozzo officially came out to the public in 2001 at a Chicago Human Rights Campaign dinner.

Too much time on his hands

To me, one of the most interesting sections of the book is when Panozzo describes the period of his life after the breakup of the classic lineup of Styx in 1984 ― the lineup that created the majority of the hits: “Renegade,” “Come Sail Away,” etc. With Styx seemingly broken up for good, Panozzo found himself financially secure but lacking daily purpose:

At the time, I thought my life was over, as I simply couldn’t see many options. I couldn’t go back to teaching. I didn’t want to join another band. After founding Styx, my ego wouldn’t allow it. But looking ahead, I estimated that I had forty more years ahead of me ― that was a lot of space to fill up.

Many people have fantasized about what they would do if they had the money and resources to do whatever they wanted with their days, but when this actually happened for Panozzo, he found himself lost and depressed in his personal ocean of free time. He acknowledges in the book that living off of royalties and investments and doing whatever you want doesn’t sound like a bad scenario at all, but for him the “winning the lottery” scenario turned into years of depression:

The rest of the population ― at least the under 70 crowd ― usually has day jobs. So there aren’t many people around to play with from nine to five. The daytime has a rhythm all its own. You have a sense that there is a lot of activity going on around you ― but you’re not a part of it. You see store clerks and restaurant workers doing their jobs. You see people in suits and briefcases rushing off to God knows where. You see service people and cops and meter readers busy doing their thing. But you reside among the day people. The day people are that strange band of folk who include the elderly, moms with young children, the disenfranchised free spirits who think working a day job is somehow beneath them ― and, of course, unemployed rock stars. It gets old fast.

While Panozzo found ways to keep busy ― he took adult education classes, spent time with family, etc. ― he didn’t fully come out of his funk until Styx reformed in 1990.

The Best of Times

Another striking aspect of the book to me is that the happiest times in Panozzo’s life didn’t always correspond to the periods when he was most successful. Moreover, this isn’t just a book about the years between when “Lady” broke on WLS and the Mr. Roboto tour. Panozzo devotes an equal amount of ink to the years when the band was relentlessly struggling to get their big break, working to promote albums on the Wooden Nickel record label that went nowhere on the charts ― Styx, Styx II, The Serpent is Rising, and Man of Miracles. He recalls of the low budget touring:

Another striking aspect of the book to me is that the happiest times in Panozzo’s life didn’t always correspond to the periods when he was most successful. Moreover, this isn’t just a book about the years between when “Lady” broke on WLS and the Mr. Roboto tour. Panozzo devotes an equal amount of ink to the years when the band was relentlessly struggling to get their big break, working to promote albums on the Wooden Nickel record label that went nowhere on the charts ― Styx, Styx II, The Serpent is Rising, and Man of Miracles. He recalls of the low budget touring:

I remember driving through the Smoky Mountains, sitting backward in one of those pull-up seats that face the rear window, with no idea where the hell we were going because all I could see were the backs of the road signs. I saw a lot of little towns that way across Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas.

While Panozzo also writes about how pleased he was to get his first monster royalty check after the band finally made it big and of how proud he was of the album The Grand Illusion ― one of the group’s bestselling ― he doesn’t seem any more happy during the platinum years as he was in the early days, the latter of which he writes: “But despite the forces pulling away from our dream, we never gave up. We kept our focus and supported each other. I’m proud of that even today.”

One of the things that made the heyday of Styx ― the ’70s and early ’80s ― less enjoyable for him was downplaying his sexual orientation (although people close to him knew he was gay, he didn’t advertise out of fear of hurting the band and of embarrassing friends and family). Despite being in one of the era’s most successful bands in the world, he found himself feeling at the time like an oddball wherever he was ― a gay man in the macho world of arena rock, and an unhip mainstream rocker around other gay men:

My personal life on the road consisted of one night stands with guys who I didn’t even tell my true identity. I rarely told them my full name or that I was in town with Styx. Of course, even if I had, most gay men would probably have no idea what I did for a living. It was my perception that not one gay man I knew cared much about rock ‘n’ roll. While I spent my life entrenched in the rock arena, an entirely different musical genre ― disco ― was taking the club scene and the gay community by storm. For my part, I didn’t care much about disco divas like Donna Summer or Gloria Gaynor, or even gay disco artists like Sylvester or Boys Town Gang. I was completely out of the pop music culture scene that was playing out at gay nightclubs across the country. Instead of dancing in clubs, I was working throughout much of the 1970s, rendering the gap between the gay community and me even larger.

Panozzo only found peace after he came out to everyone, and started speaking up on behalf of various gay causes, even though by this time he’d been diagnosed with AIDS. Near the end of the book, he reprints some of the many inspirational and positive emails he has gotten from people all over the world after coming out (for instance, one from a person in Wisconsin who was inspired by him to do volunteer work at a local AIDS network) and is clearly just as proud ― if not more ― of these than anything he describes Styx doing.

In Conclusion

I enjoyed this book, but not entirely for the main reason I believe the author wrote it. Panozzo writes in the introduction, “On the surface, it’s the story about one gay man’s struggle to come to terms with himself. But it is really about anyone struggling to come to terms with a troubling aspect of his or her life.”

For me, this message was inspirational ― and it’s clearly the main motivation for Panozzo writing the book in the first place. But to be honest, I enjoyed the book more just because I’ve been a Styx fan since being blown away by the Pieces of Eight album circa 1981. The conflict in the book that was the most intriguing to me was the one between Dennis DeYoung, who wrote syrupy smashes like “Babe” and “Lady,” and the rest of the band who were more behind rockers like “Renegade” and “Blue Collar Man (Long Nights).” Yet someone who doesn’t care about Styx could get behind the book for more universal reasons, as well.

Anyway, if you’re going to the show at Assembly Hall, enjoy! I’m not sure if Panozzo is performing at this gig or whether his replacement touring bass player is, but either way it should be a good one.

Chuck discusses The Grand Illusion for AuthorViews: