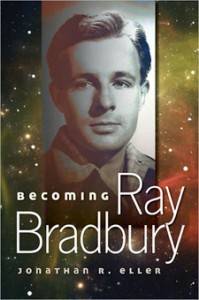

Want to know more about Ray Bradbury’s youth and early writing career? Becoming Ray Bradbury is a recent UI Press book by Jonathan R. Eller, a professor of English at Indiana University–Purdue University in Indianapolis. Becoming Ray Bradbury is a combination of biography, American history, and literary criticism. The book covers Bradbury ― who was born in 1920 ― through his childhood and adolescence in Illinois and California into his early years as a writer publishing stories in the pulp magazines of the 1940s, and ends around 1953, the year he published Fahrenheit 451, by which time he had become a major figure in American letters.

Want to know more about Ray Bradbury’s youth and early writing career? Becoming Ray Bradbury is a recent UI Press book by Jonathan R. Eller, a professor of English at Indiana University–Purdue University in Indianapolis. Becoming Ray Bradbury is a combination of biography, American history, and literary criticism. The book covers Bradbury ― who was born in 1920 ― through his childhood and adolescence in Illinois and California into his early years as a writer publishing stories in the pulp magazines of the 1940s, and ends around 1953, the year he published Fahrenheit 451, by which time he had become a major figure in American letters.

Eller responded to my questions about Bradbury’s life and work, as well as his own book, by email.

Mark Laughlin:

[By] the time I met my wife Maggie I was 25 and … I began to make plans to sell out … I wanted to sell out in the worst way because I wanted to be with her, but the wonderful thing about creativity is that once you get an idea that’s decent, even though you may want to commercialize it, you can’t. I tried to be commercial and it never worked, because my intuition was so powerful always in my life, I could never be a commercial writer.

–Bradbury in 1969 in a letter to his editor, looking back to earlier in his career before he was an enormous success.

Bradbury sold many of his early published stories during the 1940s, when he was in his twenties, to pulps like Weird Tales, and then gradually made the transition to mainstream magazines that published literary fiction, like The New Yorker. In his early days, he had stories rejected by the pulps for going outside of their usual formulas, and then in later years had stories rejected by mainstream magazines because, by that time, he was stereotyped as a “pulp” writer. Sometimes, he couldn’t win.

One of themes throughout your book is that it’s hard to put a label or genre on a lot of what Bradbury wrote. In the above quote, he’s showing a desire to fit in somewhere for the sake of making money. But how much ― if at all ― in his early career did he want on a personal level to have his work fit in more with an established style of writing? He’s a unique talent, but this wasn’t something that was always an asset for him in his early years as a writer ― was he lonely being different?

Jonathan R. Eller: The 1969 quotation is actually from a series of interviews that Bradbury worked up with his agent, Don Congdon (these were never published). By that time he had developed a somewhat dramatic way of reflecting on the first decade of his career; his correspondence of the mid- and late-1940s indicates that he never seriously considered slanting his work to make money. During the 1941–44 period, a few of his published stories show that he was still, at times, emulating such mentors as Leigh Brackett. This was a form of slanting, for he was still in the process of learning by imitating writers who did indeed write for a particular genre market and played by most of the genre rules. But once he began to develop his own narrative voice, and to write from his own life experiences, this kind of slanting disappeared from his work.

Jonathan R. Eller: The 1969 quotation is actually from a series of interviews that Bradbury worked up with his agent, Don Congdon (these were never published). By that time he had developed a somewhat dramatic way of reflecting on the first decade of his career; his correspondence of the mid- and late-1940s indicates that he never seriously considered slanting his work to make money. During the 1941–44 period, a few of his published stories show that he was still, at times, emulating such mentors as Leigh Brackett. This was a form of slanting, for he was still in the process of learning by imitating writers who did indeed write for a particular genre market and played by most of the genre rules. But once he began to develop his own narrative voice, and to write from his own life experiences, this kind of slanting disappeared from his work.

He never wrote for money, and in fact went out of his way to maintain the originality of his work even when it meant rejection. He never wrote for a magazine or a category of magazine, and his submission record shows that he often submitted stories that did not match the perceived audiences at all. Often they were rejected, but sometimes these magazines broke their own policies and published off-trail Bradbury stories. These rejections did not create a feeling of loneliness or alienation. He had good agents (Julius Schwartz for the pulps, and eventually Don Congdon for all of his work), and he always found reinforcement from them, from his wife, and from most of the editors (if not the publishers) where he submitted his work. Stories that didn’t sell (the good ones) eventually appeared in his major story collections, and have never been out of print.

Laughlin:

The fiction writer is, first, an emotionalist. A story is not successful through logic, or beautiful thinking, or by its appeal to the intellect, though these elements must be present. It succeeds in its appeal to the reader’s emotions. Many of the best beloved stories are weak in plot and idea, implausible in conception. They are great because they get under the reader’s skin, causing him to react sympathetically with the characters.

–Ray Bradbury in an early interview

There are certain Bradbury stories that made an enormous impression on me when I first read them decades ago and have stayed with me to this day: “The Crowd,” “A Sound of Thunder,” “Skeleton,” “The Scythe,” and others, but I don’t remember the characters in these stories much at all. I remember the concepts in the same way that I remember certain Twilight Zone episode concepts. Then again, I’ve only read a fraction of what Bradbury has published.

Where in Bradbury’s work do you feel he most succeeds in doing what he says is important in the above quote ― getting readers to react sympathetically with the characters?

Eller: Character development is best in Bradbury’s more realistic tales of inner consciousness, such psychological studies as “The Next in Line” and its subsequent ‘prequel,’ “Interval in Sunlight.” As I note in chapter 29 (Modernist Alternatives), these two tales are matched by another pair of interrelated tales, “The Whole Town’s Sleeping” and “At Midnight, in the Month of June.” At the end of chapter 45, we see Bradbury wondering if ‘he understood Montag well enough to provide him with motivation equal to the ideas he had given him’ (pg. 280). He would always doubt his ability to develop fully rounded characters, and in his later fiction, the characters are rarely developed. He eventually relies less on plot and character, and more on anecdote and dialog; but many of the stories of the first two decades of his career have characters of great power.

As I work on the sequel to Becoming Ray Bradbury, I find that the key to getting readers to react sympathetically with his characters is his ability to dramatize ideas and to convey the consequences of these ideas for his characters. You are right when you say that very few of the characters from his best early horror tales are memorable. But the characters of the four realistic stories I note above are deeply memorable, as is the little boy-man from “Hail and Farewell,” or Cora from “Cora and the Great Wide World.”

Laughlin:

Bradbury’s lifelong tendency to simplify an argument to its essentials evolved in this way from his working-class roots. Through his teens and into his middle twenties, he often oversimplified his argument in ways that exhibited a naiveté about politics and economics.

–From Becoming Ray Bradbury, pg. 106

Do you feel this tendency of simplifying arguments contributed to so much of Bradbury’s early work being within the form of the short story, as opposed to longer formats of writing like the novel? Having reduced an argument to its core, isn’t the short story an ideal way to present it?

Eller: His tendency to simplify an argument may very well have played into his instinctive focus on the short story form. This more or less rational process was probably secondary to the more emotional core of his creativity, which worked best when he allowed ideas to simply well up from his subconscious mind. He got that technique from Dorothea Brande’s book Becoming a Writer, but in that book she went on to show how, at some point, the rational mind takes over and begins the process of revision. That’s where the instinct you point out, the reduction of the argument to its core, probably played into his creative process as a story writer.

Laughlin:

Mother Bradbury had found a rental bungalow for the newlyweds just a block off the Venice beachfront, at 33 Venice Boulevard. Although he was only moving a half dozen blocks west from the house at 670 Venice, the change of environment was monumental for him. He was leaving a home where he was dearly loved, but where he had never been understood. His parents hardly knew the interior world of his imagination, and Skip, who was four years older, never understood it at all.

–From Becoming Ray Bradbury, pg. 157, on Bradbury getting married at age 27 and leaving the security of his immediate family’s home.

As you mention in the quote above, Bradbury had a good relationship with his family growing up, but they didn’t quite get where he was coming from with his literary pursuits during his youth and early adulthood. Your book covers Bradbury’s life into the 1950s, by which time he was already successful and acclaimed, but before he became one of the most recognized and anthologized authors in America.

How did his family react, especially his older brother Skip (the two brothers shared a bedroom until Ray was married), when Bradbury eventually became the enormous success that he did? Were they surprised?

Eller: By the early 1950s, his brother and parents were no longer surprised by his continuing success. They sensed his emerging confidence, and once his works were adapted to radio, television, and cinema his further achievements were no longer surprising. But they never fully shared these milestones. His mother had introduced him to the cinema, but she was not particularly imaginative. His father was a great reader, but was quiet and identified with the world of an outdoorsman. Skip was cut from the same cloth as their father, and his passions focused almost exclusively on the world of sports and the hard labor professions he followed to help the family make ends meet during the 1930s and 1940s. They never understood the worlds that Ray Bradbury imagined, and never really understood him at all.

Laughlin:

This is the last refuge for people who want to think at a time when thinking seems to be looked upon as something pink by too many exponents of McCarthyism in this country. I have yet to be called a communist, even though I have written stories against book burning, excessive mechanization, police and thought control and fascism in high places. I imagine that no one has thought to call me a communist because I have laid the stories in the future.

–Bradbury in 1950, on the advantages of writing in the science fiction genre

As he points out himself in the quote above, Bradbury’s fiction often deals with issues that were current at the time, even if not overtly. Arthur Miller’s 1952 play The Crucible is primarily an allegory to what was going on politically at the time. Is it safe to say that works like The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451 are the same, or is this oversimplifying what Bradbury was trying to do in these books?

Eller: Bradbury felt a great wistfulness for the simpler pleasures and passions of the past, but he was at his best with issues of the present that he could project into the future. He did not mistrust the new science and technologies, but he mistrusted what mankind might do with these fabulous new tools. In this way, works like The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451 (along with many stories collected in The Illustrated Man and The Golden Apples of the Sun) were commentaries on the times, but his approach was not as allegorical as Miller’s in The Crucible. Bradbury is a mythmaker, and his preferred medium is the fantastic tale. The rules of the universe are bent and sometimes turned inside out in his fantasies, but in the works that follow some of the rules of science fiction his focus is the same as it is in his fantasies: The human condition. He was, like many of his peers, interested in the human factor, and in these early works he continually took the measure of mankind to see if we had any hope of making it to the stars.

Eller: Bradbury felt a great wistfulness for the simpler pleasures and passions of the past, but he was at his best with issues of the present that he could project into the future. He did not mistrust the new science and technologies, but he mistrusted what mankind might do with these fabulous new tools. In this way, works like The Martian Chronicles and Fahrenheit 451 (along with many stories collected in The Illustrated Man and The Golden Apples of the Sun) were commentaries on the times, but his approach was not as allegorical as Miller’s in The Crucible. Bradbury is a mythmaker, and his preferred medium is the fantastic tale. The rules of the universe are bent and sometimes turned inside out in his fantasies, but in the works that follow some of the rules of science fiction his focus is the same as it is in his fantasies: The human condition. He was, like many of his peers, interested in the human factor, and in these early works he continually took the measure of mankind to see if we had any hope of making it to the stars.