There are some conversations at which you can’t help but wish you had been present. Conversations between world leaders, perhaps. Between great innovators or historical figures. Between Picasso and Einstein at the Lapin Agile. Obama and Oprah (but I already mentioned world leaders…).

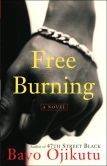

Some conversations have the flow of music, whether languid or intense or, in some cases, as spiky and fascinating as jazz. One such conversation follows, as Smile Politely continues its coverage of Pygmalion Lit Fest. Steve Davenport, a prolific and interesting writer in his own regard, interviews Bayo Ojikutu, who will be featured at the Pyg Lit Fest at the end of the week.

Oh to have been a fly on the wall. (MG)

********

Smile Politely: Greetings, Bayo. A couple of months ago at my website, I wrote about you and another Chicago writer. How has your life changed since then? Agents and NYC publishing houses knocking your doors down?

Bayo Ojikutu: Everything has been in the porcelain shitter since you and Gasoline Lake bathed me in foul attention. Jokes, jokes, these are but jokes right here. It’s been quite the brilliant swirl. All right, I’m done plugging this shitter.

SP: Talk to me about the role Chicago played in your development as a writer.

Ojikutu: My family moved to the southern outskirts of the Chicagoland area when I was young. Leaving the city for suburbs sprawling over onion fields and downsizedsteel mills left me longing for something I could understand as city life. So when I started writing shortly thereafter—once I grow out of aping Spielberg Hollywood fantasy on the page—I aimed to create the city that we left, or recreate as much as I could have possibly known of it at that young age. In my earliest stories, Chicago as narrative landscape ends up an amalgam of half-faded memory, bits from the 5:30 news, and a first generation flyover kid’s take on Salinger’s and Scorsese’s New York. A pastiche of the urban as landscape, as that’s what I missed, and what I found captivating, I suppose. Maybe some of my understanding of Chicago as “real” place put to fictive use can be read in 47th Street Black. Free Burning, on the other hand, is set in a  portion of a place in which I actually lived as a youth—set in the neighborhood of my early youth, some thirty years after I lived near there—yet the place as I name it does not exist on any of the city’s published grid maps. Four Corners? No such thing except that, it’s all about trappings, and characters who knowingly, and less so, sense themselves confined, and all that which that series of city blocks represents to them as the beginning and end of home. The place is a contrived riff on the portion of South Shore that we’d drive through on our ways here or there when I was a child, the some place found a few miles south and east of our current home. More real in ways, I think than the studied 47th Street thoroughfare that courses through the Chicago of an earlier time.

portion of a place in which I actually lived as a youth—set in the neighborhood of my early youth, some thirty years after I lived near there—yet the place as I name it does not exist on any of the city’s published grid maps. Four Corners? No such thing except that, it’s all about trappings, and characters who knowingly, and less so, sense themselves confined, and all that which that series of city blocks represents to them as the beginning and end of home. The place is a contrived riff on the portion of South Shore that we’d drive through on our ways here or there when I was a child, the some place found a few miles south and east of our current home. More real in ways, I think than the studied 47th Street thoroughfare that courses through the Chicago of an earlier time.

SP: After those novels, is Chicago still your authorial turf? And do you encourage your students to make place as important as the characters they create?

Ojikutu: My turf? Maybe the industrial portion of the Midwestern US, or the end of that industry, some snapped twain of commerce, this last, best rust empire. Chicago has been the setting of most of my work, in one way or another, both long and short work. But I can’t say—don’t want to, at least—that it’s mine. The sense I see of this place, as the middle of the end, of something—I’m certain this is not the sense most lifelong, deep down Chicagoans make of the place. I guess I put my understanding of this urban quarter to use as narrative turf in effort to make sense of someplace else. Not to say that other place is mine, either.

Riffing on Jane Smiley and RV Cassill, I believe there are five elements of fiction at work in all narrative. Action. Character. Language. Setting. Theme. Of them, settingis as essential to storytelling, in my mind, as are action and language. Right there with them, at least. But I like what the science fiction writers and the poets and the War-time jazz instrumentalists do with place and time. Create all new realms, splay them all about the page, make the stage bounce, swing tempo. I respect that. Like the Bottom and Gasoline Lake in your work, Steve, those space settings invigorate something on the page that is right there, the place where these characters are, when they are, what they know. Such fictive places both capture narrative voices and live beyond characters’ lives, neither bound up in the ethos of place nor in notions given us by the discipline of sociology nor the notion of reality.

SP: What are you working on now? And will you be reading from that project at the Pygmalion Lit Fest?

Ojikutu: A third novel set in a mostly cooked-up place. [Re: reading:] I’m thinking, a week-out, yes. Probably so. Looking forward . . .

SP: Final words? Have any?

Ojikutu: In honor of this festival set in the midst of the center of the Illinois corn stalks, I think we should all fall in love with something that we’ve created with our own hands. I’m still searching for the due object of my own affection on the page, so, nothing final, no. Just more words.

Check out Ojikutu at Pygmalion Lit Fest on Friday at Cafeteria & Company. Readings start at 6 p.m.