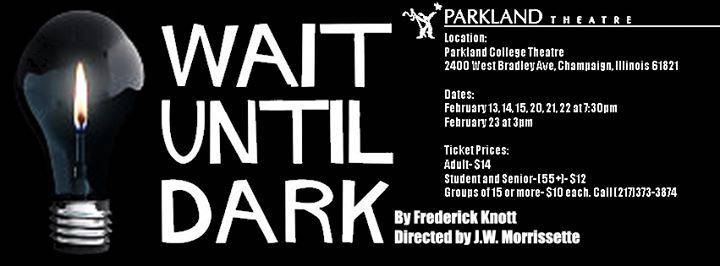

The play Wait Until Dark by Frederick Knott is being presented currently by Parkland College Theatre, and the last performance of this production is on Sunday, February 23rd. For information and show times see the Parkland Theatre’s website, and for an in-depth preview of the production itself, read this preview SP article by Mathew Green (or his review here as well).

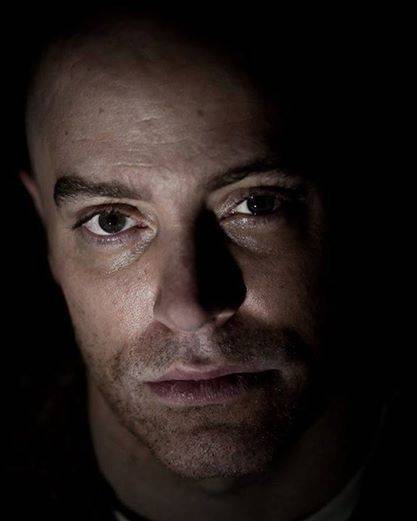

Wait Until Dark is a tense thriller where a woman who is blind finds herself matching wits with three criminals — one of them who is extremely brutal. The play was originally performed on Broadway in 1966. In the current Parkland production, the role of Sam Hendrix — the husband of the protagonist who is blind — is played by local actor Monty Joyce. After seeing the play at Parkland myself, I emailed Joyce some questions who emailed his answers right back.

Smile Politely: For the majority of the play, your character is not actually on the stage. However, he is a big presence in the protagonist’s mind as she anxiously waits for his return. What it’s like having a role which must be a bit like playing Godot?

Monty Joyce: It was a welcome challenge. A key plot point is hinged on whether my wife Susy trusts her husband Sam, or the story of the men who tell her that Sam isn’t quite as truthful as she has believed him to be. I have a few crucial minutes to interact with wife before I take off on my trip, and I wanted to convey Sam’s character to the audience so that they could more accurately judge what kind of man I am — and therefore decide whose story was the more plausible. I hope the nuances of my portrayal help the viewers make the right decision on whom to trust.

SP: Your character is trying to help his wife adjust to being blind. He assigns her various tasks and challenges such as defrosting the refrigerator, walking outside without asking for assistance, etc. He scolds her for things like wanting to just dial a telephone operator for help instead of memorizing phone numbers herself. The guy means well, but he’s also a little bossy. Did you ever feel like he crosses the line between caregiver and jerk?

Joyce: Some of the cast and crew made disparaging remarks about Sam during the production, but I stand behind his behavior and I know he’s doing right by his wife. He is an ex-Marine sergeant and, yes, he knows and stresses the importance of discipline. He doesn’t do this because he’s an authoritarian and gets off on power trips riding harshly on his blind wife. He’s like this because discipline saves lives in combat and enhances the quality of life by harnessing reality to one’s will. He loves the hell out of Susy and the tougher he is, the less coddling he gives his little lambikin, and the easier, richer, and more fulfilled her life and their lives will be in the future. Beneath his taskmaster armor is a man of kindness, foresight, and concern. He’s quite a lovely man. I wish I were more like him, honestly. He’s a strong, sexy guy who’s also a playful goofball.

SP: You deliver quite a few lines facing a wall of the set with your back to the audience. How did that work for you?

Joyce: It reminded me of the fact that acting is much more than declaiming. Good acting is living truthfully in imaginary circumstances, or at least convincing the audience that you are. I took acting lessons in the Sanford Meissner technique back in the late 1990s — a discipline that stressed accurate doing of real tasks as equal in importance to speaking and listening to your fellow actors. Since I got back into acting almost three years ago, this role draws on more of that training than any other part I’ve played. Sam is developing pictures, packing for his trip, and smoking a cigarette all while trying to make sure that his blind wife Susy knows what she has to do while he’s away. The cigarette was the most daunting of the tasks for me because I wanted it to look second nature, not like a dorky actor pretending to smoke. Eventually, I found myself drawing on memories of my father who could do just about anything with a cigarette in his mouth, including pitching practice for little league. You don’t see much of that on ball fields nowadays, fortunately.

SP: The play is set in 1965 in Greenwich Village. In your opinion, how important are the time period and setting to the effectiveness of the play?

Joyce: It would be foolish to try to update this play to present times because communications technology has changed so much. This nefarious scheme could not be carried out in a contemporary milieu of smartphones. And the mid-sixties NYC setting evokes an urban atmosphere almost quaint yet semi-seedy. It feels kind of like Barefoot In the Park, but with drugs and sadism and terror to drain the blood from your face and make you squirm in your seat. The story is set at a time when crime rates and illicit drug use, particularly in the inner city, were beginning their ascent. Fear of violence, especially drug-fueled violence, was becoming a concern to people who would not have worried a jot about such things less than a decade before. As Greenwich Village resident Bob Dylan sang, “the times they were a changin'” — and not all for the better. The Village, where Sam and Susy live in a small basement apartment, was then — and still is now — a neighborhood where the fashionable and the bohemian and the raffish and the dangerous all intermeddle. Heroin is all of those things. I’ve read that during the 60s, more than half of all the heroin sold in the U.S. was sold in New York City.

SP: Is there a message to this play or is it pretty much just an edge of your seat thriller?

Joyce: You’re right in that’s an edge of your seat thriller, and one of the best I’ve ever read or seen written for the stage. It engages senses and instincts that TV and movies simply can’t. It’s the best kind of 3-D entertainment. Message? Don’t be a menace while stealing horse in the hood? Always keep an extra knife or two at hand? Or, to quote Damon Wayans’ Handi-man from In Living Color: “Never underestimate the power of the handicapped.”

SP: How did this role help you develop as an actor? What’s next for you after Wait Until Dark is over?

Joyce: This role strengthened two beliefs of mine — truisms which have to be internalized and lived out to realize their truth so that they are not platitudes:

- There are no small roles just small actors, and

- Acting is as much or more about listening as it is about speaking.

As for what’s next after this show, probably me sitting in a dark room weeping. This is the third show I’ve done since September and none are in the offing, at least until summer, so having my evenings free will be disconcerting. Maybe I’ll have to get some sort of “real life” for a couple of months.

SP: Any other thoughts for Smile Politely readers about acting and drama in general and this production in particular?

Joyce: Yes, and that is that acting and drama in general are alive and dancing in Champaign-Urbana. With every show I do, I’m more and more impressed with all the talent and effort and execution of the directors, technicians, scene and lighting designers, actors, promoters — everyone. Somehow I’m not jaded yet. And I love that Smile Politely helps promote and analyze and celebrate it all in such with intelligence and enthusiasm.

In the coming weeks I plan to see The Clean House at the Station Theatre; CUTC’s You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown; and this Spring’s Parkland Musical Spamalot and I encourage everyone to see them too.