To be perfectly honest, I don’t really care for war. I know, crazy, right? What’s not to love? But I’m a bit of maverick in that regard. What can I say? The idea of a bunch of nations getting together for one giant kill-fest, to me, just seems like it’s in bad taste. Bombs go off, limbs detach themselves from bodies, bullets dart around in the air, people get perforated, buildings crumble, borders shift around (shrinking and growing depending on who’s doing well and who’s doing poorly) and in the end a lot of boxes get filled with chunks of people (what very little sometimes is left of them) and buried in the dirt. All in all, it’s fairly predictable and sort of depressing. That being said, like any horrendous act in life, it always seems far more interesting in retrospect. We, as human beings, have that weird ability to whistle past the graveyard and laugh at our own misfortunes. Case in point: I find books about serial killers fascinating, but whenever I see an article pop up on my news feed or if I catch a report on television about some guy driving around dismembering lot lizards, I get all queasy and turn away; but reading about these acts later on down in the line, analytically laid out and perfumed a bit with some grandeur, catches my interests and compels me, in a somewhat Grand Guignol-like way, to edify myself about the dark aspects of life.

War is no exception. I like to read about the wars of our past, not just in this country, but all around the world and through all the annals of history (with a particular emphasis on Roman days — Oh, Nero, you funny little devil you). War, for better or for worse, yields some dramatic imagery. La Grand Guerre, exhibiting at the Krannert Art Museum from August 29 until December 23, features French posters and photographs from World War I. The images are an amalgam of emotions and themes, both haunting and uplifting. The exhibit, curated by David O’Brien and Pauline Parent, is an interesting criss-cross of overtly patriotic images and honest glances at the tiresome weight of war.

War is no exception. I like to read about the wars of our past, not just in this country, but all around the world and through all the annals of history (with a particular emphasis on Roman days — Oh, Nero, you funny little devil you). War, for better or for worse, yields some dramatic imagery. La Grand Guerre, exhibiting at the Krannert Art Museum from August 29 until December 23, features French posters and photographs from World War I. The images are an amalgam of emotions and themes, both haunting and uplifting. The exhibit, curated by David O’Brien and Pauline Parent, is an interesting criss-cross of overtly patriotic images and honest glances at the tiresome weight of war.

While touring the exhibit, a showcase culled from a mass collection of 105 large posters and approximately 4,500 photographs, I found myself walking around, diligently jotting down my own descriptions of each poster and photo (since I was warned that photography was not allowed); after writing the description of almost every poster I saw, I began to set a sense of the collection as a whole. When it comes to propaganda, I’ve found that there are usually common themes & recurring images. Often you’ll find a group of soldiers gesticulating in various heroic poses, a smear of bloody battlefields, and, more often than not, you’ll see a few anthropomorphic personifications of liberty and freedom. La Grande Guerre delivered this and more.

One particular piece that caught my attention was a poster titled Pour la France Versez Votre or. L’or Combat Pour la Victoire (translated: “Deposit Your Gold for France. Gold Fights for Victory,” left), which features a rather surprised looking soldier being verbally accosted by a giant golden rooster popping out of a coin. The poster, as the titled subtly suggests, demands (or at least strong advises) that the people of France give up their shiny coins in an effort to help out with the war.

One particular piece that caught my attention was a poster titled Pour la France Versez Votre or. L’or Combat Pour la Victoire (translated: “Deposit Your Gold for France. Gold Fights for Victory,” left), which features a rather surprised looking soldier being verbally accosted by a giant golden rooster popping out of a coin. The poster, as the titled subtly suggests, demands (or at least strong advises) that the people of France give up their shiny coins in an effort to help out with the war.

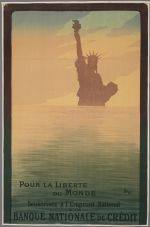

Another poster, painted by Serge Goursat, titled Pour la Liberte du monde. Souscrivez a lemprunt national a la Banque National de Credit (“For Freedom of the World. Subscribe to the National loan at the National Credit Bank,” below right) depicts an apocalyptic image of the statue of liberty submerged in water up to her breast bone — conjuring in my mind the final scene from Planet of the Apes (which is based on a French novel, so do with that tidbit as you please).

Both these posters are great examples of themes used in propaganda: they are patriotic; they are fear-inducing; and they are, to be honest, snazzy and really neat looking. They catch the eye and quickly inform you of their message, without wasting any time with subtext. They say to the viewer, Hey, pal, this stuff isn’t that complicated, alright? Be a hero. Give us some money or sign up for the war, and this whole thing will be over before your country sinks into the maw of the sea. Trust me, it’s the cool thing to do.

Both these posters are great examples of themes used in propaganda: they are patriotic; they are fear-inducing; and they are, to be honest, snazzy and really neat looking. They catch the eye and quickly inform you of their message, without wasting any time with subtext. They say to the viewer, Hey, pal, this stuff isn’t that complicated, alright? Be a hero. Give us some money or sign up for the war, and this whole thing will be over before your country sinks into the maw of the sea. Trust me, it’s the cool thing to do.

When it came to the photography, most of which is housed in two slab-like display cases fixed at the opposite ends of the exhibit, you find another angle of the story. The photos, commissioned by the Photographic Service of the French Army, are more truth-telling. That’s one of the great things about photography: whether it is intended or not (and I’m assuming in this case it wasn’t), the images presented in photographs can’t help but ooze a bit of honestly, no matter what kind of pretext you try to use on them. The photos show off small frozen moments of captured emotions that can’t easily be misconstrued.

Photography has the same kind of unfiltered honesty that you’d find in a rambling toddler. Without frill or vitriol they present you with images of soldiers limping or marching through sludge; towns collapsing in on themselves like emptied stars; zeppelins in various states of flight; trenches overstuffed with guns and canisters of gas; and a lot of people sitting around, smoking and drinking, in buildings that used to be churches or homes and now are really just giant piles of potsherd. Posters, though sometimes honest & engaging with one’s emotions, are usually more idyllic and symbolic. It seems to me that some of the most popular themes in propaganda are guilt & shame. The posters will often demand money and support and patriotism, reminding the viewer that it’s their duty to give whatever they have (sometimes money, sometimes life) for the effort of their country; and, if that doesn’t work, the poster will use grandeur and sweeping images, like the depiction of an Angel of Liberty wielding a sword and guiding a cadre of soldiers down from Heaven, to try and stir some kind of latent heroics in the viewer.

Photography has the same kind of unfiltered honesty that you’d find in a rambling toddler. Without frill or vitriol they present you with images of soldiers limping or marching through sludge; towns collapsing in on themselves like emptied stars; zeppelins in various states of flight; trenches overstuffed with guns and canisters of gas; and a lot of people sitting around, smoking and drinking, in buildings that used to be churches or homes and now are really just giant piles of potsherd. Posters, though sometimes honest & engaging with one’s emotions, are usually more idyllic and symbolic. It seems to me that some of the most popular themes in propaganda are guilt & shame. The posters will often demand money and support and patriotism, reminding the viewer that it’s their duty to give whatever they have (sometimes money, sometimes life) for the effort of their country; and, if that doesn’t work, the poster will use grandeur and sweeping images, like the depiction of an Angel of Liberty wielding a sword and guiding a cadre of soldiers down from Heaven, to try and stir some kind of latent heroics in the viewer.

The dichotomy of the two types of images — the painfully honest photos and overly embellished art — is fascinating.

It might not seem it when glancing over it as a whole — a few colorful posters and some black-and-white photographs; but if closely inspected, the exhibit will inform and amuse. You can laugh at some of the absurdity of the posters, drink in the history of the images on display, or, at the very least, appreciate the artistry and craftsmanship that went into creating some of these memorable pieces of artwork.

It might not seem it when glancing over it as a whole — a few colorful posters and some black-and-white photographs; but if closely inspected, the exhibit will inform and amuse. You can laugh at some of the absurdity of the posters, drink in the history of the images on display, or, at the very least, appreciate the artistry and craftsmanship that went into creating some of these memorable pieces of artwork.

I can understand a half-bemused appreciation for the images on display. I’m not suggesting that the viewer will become swept up in a glorious wave of patriotism, but I think that the show in its entirety is intriguing and well worth a viewing.

The thing about art is that it’s almost a phantom limb of life. It’s unconnected and yet reminiscent of a life lived by another. The exhibit La Grande Guerre is a slice of a distant time and place. It’s interesting, inspirational, even humorous, and altogether defining of humanity. Art is a tool used to express and to evoke emotions, but art can also be an advertisement. In the case of propaganda, it’s a mixture of the two.