Superheroes are everywhere now, in every part of our culture. Comic books have been with us for generations, of course, as have cartoons, action figures, Halloween costumes, and fanciful lunchboxes. The warring factions of Marvel and DC Comics (homes of the Avengers and Justice League, respectively) have given birth, directly and indirectly, to numerous independent comics imprints, and images of Spider-Man, Superman, and Batman are ubiquitous and universally recognized. It should come as no surprise, then, that superhero culture, having moved out of the realm of Saturday morning cartoons (remember those?) and taken over a goodly chunk of primetime TV and most of the billions of dollars spent and earned on motion pictures, has also become more prevalent in the theatre.

That’s neither a good nor bad thing. Any play, regardless of its subject, can still be great, depending on how the subject matter is handled. Good writing is, after all, still good writing. But that’s the lynchpin, right there. The writing. Is it possible to take a well-written play and cock it up? You bet. I’ve seen bad Shakespeare, bad Williams, et bad cetera. And, on the flip-flop, I’ve seen really well-acted, well-designed, well-intentioned productions of plays that were simply not that good.

This is where we join today’s broadcast already in progress.

I’m no scientist, but I do know that there is a process by which one can take something murky and inelegant — say, a lump of coal — and transform it, through determined effort and concentration, into something quite lovely. That is the best analogy I can offer to explain my feelings about Parkland College Theatre’s current production, The Sparrow. And, backhanded though it may seem, I do mean it as a compliment.

I’m no scientist, but I do know that there is a process by which one can take something murky and inelegant — say, a lump of coal — and transform it, through determined effort and concentration, into something quite lovely. That is the best analogy I can offer to explain my feelings about Parkland College Theatre’s current production, The Sparrow. And, backhanded though it may seem, I do mean it as a compliment.

Attributed to playwrights Chris Mathews, Jake Minton, and Nathan Allen of the House Theatre of Chicago, this story-theatre play depicts the homecoming of Emily Book, a high school senior returning to her hometown ten years after a tragedy that claimed the lives of the rest of her grade-level peers. (Long story short: after dropping Emily off at her ramshackle house literally on the wrong side of the tracks after a class trip, the school bus was struck by a train, killing the rest of the students and the bus driver.) Much trepidation surrounds Emily’s return, from both the townspeople, still understandably shaken by past events, and Emily herself, who carries the guilt of a survivor… and perhaps more.

It is decided (in a nifty Town Hall opening that incorporates the audience and shows off Parkland’s new black box environs) that Emily will reside with Joyce and Albert McGuckin, who happen to have lost their daughter Sarah in the bus crash lo those many years ago. As the McGuckins, Chelsea Zych and David Heckman do some lovely work, wringing emotion from relatable but underwritten characters. Heckman is solid and subtle, doing no more or less than is required (which is to be admired in a supporting player). Heavier lifting is asked of Zych, as Joyce is mandated by the script to swing between nicely nervous and completely distraught. Zych pulls this off and manages, in her few scenes, to leave the audience shaken.

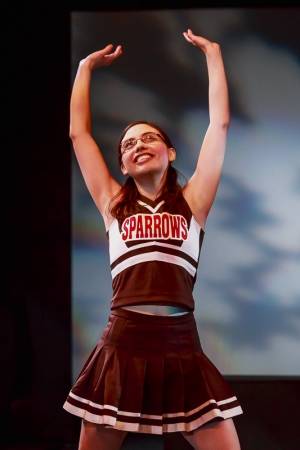

Her domestic situation settled, Emily still faces some small amount of whispering and skepticism, but she is quickly folded into school life with the help of a popular student (Jenny McGrath, played by Jelinda Smith, pictured far left) and a cool young teacher (Mr. Christopher, played by Joey Moser). Moser and Smith bring a lot of personality to their roles, adding dimension to characters that begin well but then lapse into plot devices (more on that later). Moser’s Mr. Christopher is funny and likable, walking that line between seeking the acceptance of his students and laying down the law. And as Jenny, Ms. Smith adds a little edge to the head cheerleader’s sunny openness. (You don’t become cheer captain, student body president, and top of your class just by being nice, after all.)

Her domestic situation settled, Emily still faces some small amount of whispering and skepticism, but she is quickly folded into school life with the help of a popular student (Jenny McGrath, played by Jelinda Smith, pictured far left) and a cool young teacher (Mr. Christopher, played by Joey Moser). Moser and Smith bring a lot of personality to their roles, adding dimension to characters that begin well but then lapse into plot devices (more on that later). Moser’s Mr. Christopher is funny and likable, walking that line between seeking the acceptance of his students and laying down the law. And as Jenny, Ms. Smith adds a little edge to the head cheerleader’s sunny openness. (You don’t become cheer captain, student body president, and top of your class just by being nice, after all.)

At school, there are classes and dodge ball and detention, all of these staged with minimal fuss and relatively smooth, simple set changes. As the other teachers and students, the ensemble cast is incredibly game, everyone playing at least two roles and putting their all into characters who are (pardon the pun) paper thin. The faculty fares best, and Warren Garver (as the school’s principal) and Jace Jamison (as the coach) distinguish themselves with comic timing and vocal inflection. The rest of the ensemble, who make up the student body as well as the population of the small town, are less defined but enjoyable throughout.

Speaking of the double duty done by the ensemble, I should mention here that the costumes worn by these actors are spot-on. The adult townsfolk are clearly distinguishable from the students, even though they are played by the same handful of actors, and the high school attire — from the t-shirts to the homecoming dresses — perfectly represents small town Midwestern life. Another fine job by Malia Andrus.

This brings us to Emily Book herself, and I cannot heap high enough praise on Karen Hughes (pictured right). She is totally natural in her demeanor and her delivery, her awkwardness hinting at deeper darkness. I can’t think of better casting for the role. When it is revealed that Emily does, in fact, have superpowers (no spoiler there—it’s on the Parkland website), Hughes makes Emily’s bravery, elation, and guilt terribly real.

This brings us to Emily Book herself, and I cannot heap high enough praise on Karen Hughes (pictured right). She is totally natural in her demeanor and her delivery, her awkwardness hinting at deeper darkness. I can’t think of better casting for the role. When it is revealed that Emily does, in fact, have superpowers (no spoiler there—it’s on the Parkland website), Hughes makes Emily’s bravery, elation, and guilt terribly real.

Speaking of “real,” I’ll say that many — if not most — of the interactions between characters show intention and genuine emotion, which is not easy with such choppy and episodic beats. The visual and audio effects are clever, making use of both projection screens and low-tech elbow grease, and the stripped-down scenic implements make this exactly the type of play to show off the new theater space and what it can do. There are very effective moments created through sound design (railroad crossing bells, for instance) and simple manipulation (a flock of book-birds that couldn’t be simpler or more evocative).

Now the bad news, and I’ll say this as gently as I can… If I had been told, prior to attending this performance, that The Sparrow was the result of a statewide contest in which the winning fifth-grader’s play would be presented as written by a bunch of grown-ups, I would have walked out of the theater thinking to myself, “What a clever little guy or gal.” I mean, sure, there are character reversals that threaten to give the audience whiplash, and certainly this play has no concept of consequences, but then neither does the average eleven-year-old.

This script calls for a couple of very specific actions in its second act that have very little basis in the words or deeds that came before. In fact, it occurred to me both while reading the script and while watching the performance that these actions seem only to occur so that something later can happen. I won’t spoil what these actions are, but I’ll say that they involve students and teachers and reiterate that none of this is the fault of the actors on stage. Sometimes a good actor just has to grin, bear it, and squeeze that piece of coal.

Make no mistake: this is a good show, and I do recommend it. I have no doubt that audience members will leave feeling satisfied and rewarded, some of them having seen a type of theatre they had never previously experienced. For that, I tip my hat to The Sparrow’s entire team. Under the direction of Gary Ambler, the cast and crew of this production have crafted an evening’s entertainment that is, in my opinion, way better than it should be.

The play continues through March 1st, but tickets are becoming scarce. Contact the Parkland box office at 217-351-2528 or through the Parkland website soon if you’re of a mind.

Photos by Scott Wells/EddieScott Photo.