They walk slowly, black blindfolds wrapped around their eyes. Krannert’s main lobby provides an obstacle course of glass cases, tables, chairs, stairs and patrons. But these few dancers are calm. Collected. No boundaries of a stage limit their movement; they’ve broken the fourth wall completely, opting to weave their November Dance preshow performance into an awaiting crowd outside a theater.

Accidental “performers,” the audience at first resists – perplexed but compelled to hold confused musings to a collective whisper. Then silence. They break to allow more space for students in Professor Susan Becker’s Sew and Flow class to move.

Clad in their own self-designed clothing creations, the students mix with patrons filling the space outside Colwell Playhouse, a theater at the University of Illinois’ Krannert Center for the Performing Arts. Their movement is subtle yet deliberate, articulated and persistent in trajectory. Some create lines of disarray with their converging paths while others take to the perimeter and pause.

A smile spreads across Becker’s angular face. Her short, reddish brown hair is tucked behind her ears beneath the stems of her glasses. She stands in the background beside improvisational dance professor Kirstie Simson, smiling too. They had done it. The culmination of their first collaborative course meshing fashion design with dance finally had an audience.

Becker, the only fashion design professor on campus, loves this moment: a moment when she knows her students understand something about style. A moment when articulate movement becomes a seamless construction of cultural conversation through dance and design.

A chime breaks the silence.

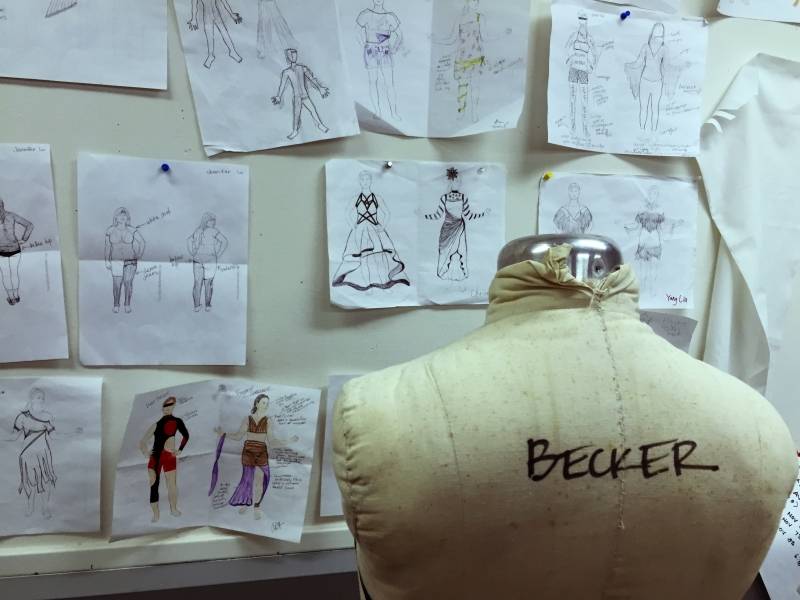

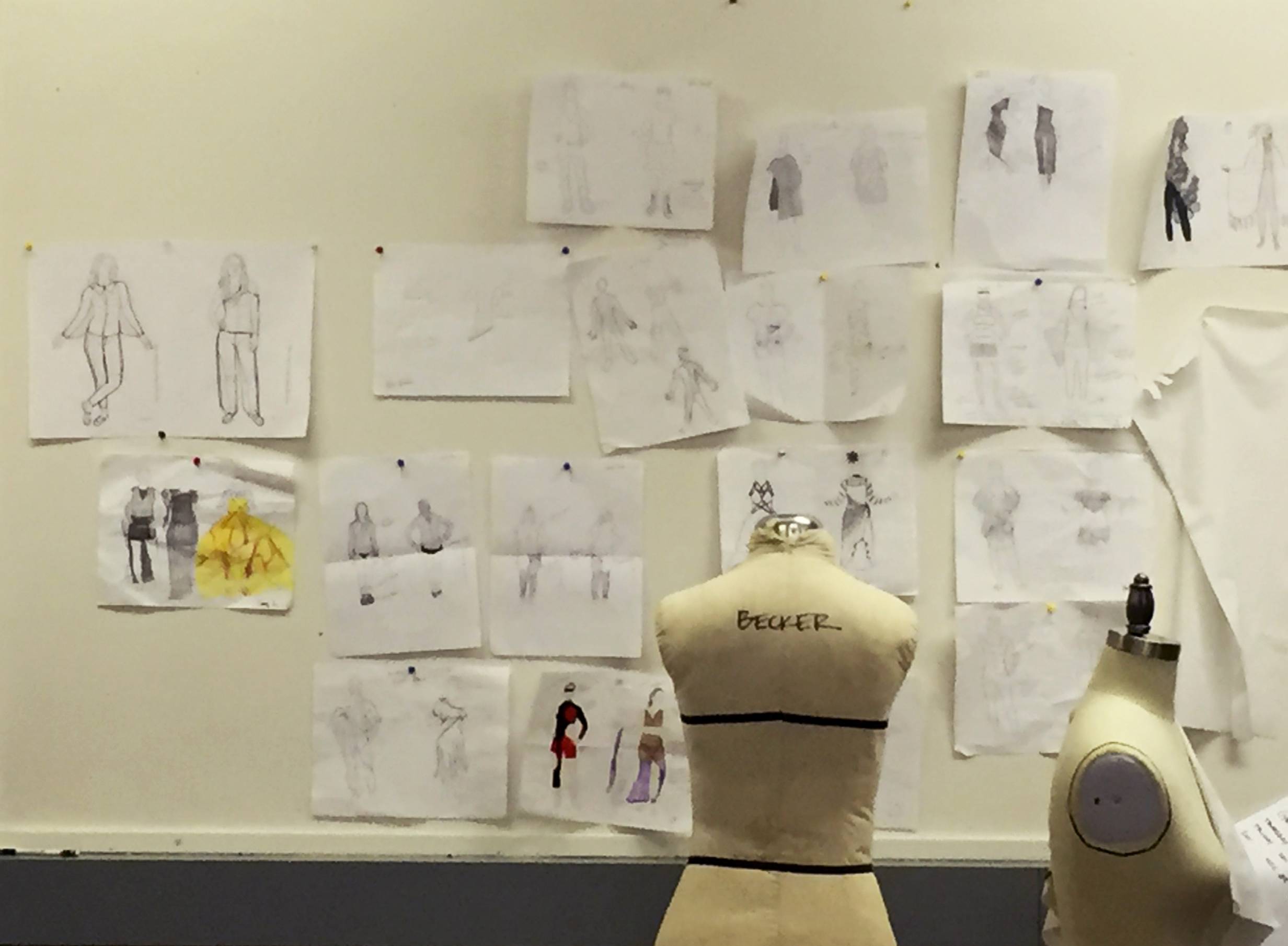

“I learn a lot from my students,” Becker said while poised on a chair in her new classroom at Noble Hall. The University had finally moved her to a room of her own, and she wasted no time in turning it into a creative space. Scraps of fabric lined tables circling the small room; plastic cartons of thread, tape and glue decorated each tabletop; bare dress forms stood speckled with pins in the middle floor space. Becker sat, legs crossed, comfortable. At ease surrounded by sewing machines, ironing boards and materials that never quite lend themselves to organization – a design professor’s confounded clarity missing only its students.

This year marks the first in three that Becker’s classes are listed under Art and Design. Previously, her courses were found listed under the Dance Department at UIUC through a little digging by students and a lot of her own promoting.

“I loved my time in the dance department. And I’m so glad I established connections there. But it doesn’t make a tremendous amount of sense that it would be listed under dance.”

Demand for fashion has changed. Freshmen enter the University looking for an opportunity to delve into design. It took some convincing, but Becker stood her ground advancing talks all the way up the chain.

“Moving an institution like this is an iceberg. But I just keep pushing at that giant beast hoping we can turn it.”

Susan Becker’s passion for teaching stems, in part, from her time as a little girl in the early ‘70s growing up in El Paso, Texas. Her mother, a much-loved drama teacher in town, costumed for a production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” She sewed fairy dresses out of torn, dyed parachutes – gossamer creations in varying shades of green. After the production, Becker remembers trying on one gown completed by a tall, glittering crown stored in the family garage.

“I just remember feeling so incredibly transformed… I felt different from the outside in,” Becker said, shifting to sit taller in her seat. “I hadn’t really, fully had that feeling before of just carrying myself differently and feeling like a different person because of what I put on.” She grew fascinated by the transformative ability of clothing.

Her father’s work moved the family across the country from Texas to New Jersey to Salt Lake City and back to Jersey. Their destinations were markedly varied, but Susan was inspired, challenged to push boundaries.

Becker spent just one year in Salt Lake City, her high school sophomore year. The Mormon Church held an overwhelmingly strong presence in Salt Lake that made for a stark contrast of order and discipline during the day to a music-centric subculture nightlife. A variety of musicians came through the city playing to the angst-ridden rebellion of the area’s youth. When Becker and her friends were not out dancing at nightclubs, they were raiding their parents’ closets and thrift shops for outfits to wear to these concerts. She used to sport collections like ‘50s knockoff Dior structured suits paired with ‘60s-inspired bold flare. Eventually, Becker started creating her own designs splattering paint and printing French phrases on any fabric she could find. In a town better known for its lack of diversity, it was the best way she knew how to express herself.

“I ran the gamut,” said Becker crossing her arms over her crossed knee bending forward as she laughed in her chair. She realized that she enjoyed evoking a strong reaction from the people who saw her. Enjoyed creating a persona through clothing based on whatever moved her. She hoped to stir something, get people thinking about the way they are perceived by what they wear.

“You’re on your own, you get to invent,” said Becker. “It felt very free.”

Salt Lake City counterculture gave her confidence, but moving back to New Jersey gave her New York City streets as a catwalk. The late ’80s City art scene exploded with exhibits like Jean-Michel Basquiat’s bright graffiti-inspired creations. Becker remembered seeing this artist install some of his work across the street from “Area,” a club she frequented.

That same night, she had decided to wear a particularly bold jacket sporting a variety of oddball objects sewn to it – including a rubber chicken.

Bouncers at Area were amused.

“Yeah, they dug it. They let me in,” Becker rolled her eyes turning up her nose to mirror a mock-haughty version of her younger self and smiled.

Becker had another fascination, one she explored during an anatomy course at Brown while she attended Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). The human body, how it was structured, how it worked, moved and provided the frame for fashion design – it captivated and inspired many of her most eccentric works.

One RISD assignment, called an “innovative,” asked design students to form a wearable outfit out of unusual material – an idea she emulates today in her own design class where she asks students to create garments out of unusual material paying particular attention to the way each fabric moves.

Considering anatomical framing is crucial when costuming for dancers. Becker’s Sew and Flow class became an exploration of blending the two via the designer and dancer meshing roles. Designers dance in their own creations and dancers design their own costumes.

“So much could have gone wrong. And instead it was just creating and being confident and walking through the fear.”

Sew and Flow was a collaboration between Simson and Becker, who agreed on the conversational property of fashion and dance together. The dance professor saw this course as an opportunity to explore the communal aspect of issues in society. In the wake of popularized gender role/gay rights activism and diversity in race relations, there was plenty to talk about.

“Society as a whole is really grappling with ‘What does gender identity mean?’ and ‘Does a person have to choose?’ and ‘How does your clothing contribute to that or not?’” Becker said. “It’s amazing how quickly those conversations are happening.”

Students were encouraged to touch on any cultural issues that affect them personally or as part of a group. The final project — the November Dance preshow in Krannert’s lobby — aimed at hitting these varied issues.

In preparation, the class met twice a week. Mondays were for designing and learning the intricacies of molding fabric around a bodice anticipating movement. Wednesdays were for dancing and talking about how the costumes looked, how they made the students feel. Becker wanted her students to learn the language of fabric, draw attention with movement – spark conversation on various levels. Technique was strict. What they did with it had limitless potential.

One Monday Sew and Flow class session focused on fitting zippers to fabric. It was a technical day, but that made for no shortage of laughter and conversation.

Simson found her seat next to the lone dance major left in the room, Clare Hansen, a transfer student from Wyoming..

“It’s been awesome in the true sense of the word: inspiring awe,” said Hansen, her tiny frame seated backward in her chair, legs up on the backrest, dangling her feet, a conscious participant in fashion design’s cultural perspective.

She looked over at Becker circling the room with colored zippers for each student to begin sewing. A smile spread across the professor’s face as she greeted each of the students.

“She has infinite amounts of knowledge, and she’s really encouraging about discussion,” Hansen brought her feet down to the floor, her gaze shifting back from Becker. “She really gives a damn about what we have to say.”

Fashion always excited Becker, but becoming a full-fledged designer out on her own never had quite the same appeal. Right out of college she began working for designer Michael Leva. For the first time she had a front row view of the daily catastrophes that can afflict a designer with his or her own label. “I saw at every level, you could go out of business in an instant by something you had absolutely no control over,” said Becker shaking her head. Teaching became a way to work with what she loves and inspire students around her to reach their full potential in design or simply discover what creating fashion can mean.

The same woman who once sported a flour sack dress with Mohawk- spiked hair now provides a blank canvas for her students. Black is the primary color of her wardrobe. It helps her transition from her role as professor to mother of her young twin boys, Simon and Cameron. Moreover, she believes it helps her students further the fashion conversation on their own. In black, in the background, she can help her class color their own understanding of the way the world moves.

“I love the conversations that I can have,” said Becker eyes-widening with her smile once again. “I think that class began the conversation of letting go and setting the bar a little higher than what you think the students can hit.”

Becker’s voice softened, her eyes closed for just a moment as she took a breath and opened wide as she exhaled to a whisper, “And then they hit it.”

This was her greatest success – the one that mattered most to her.

“I’m really proud that I felt that that piece was able to do what we want art to do. I was so excited that I was successful in being able to lay the foundation that they built upon. If I can create an environment where students feel safe to really express their opinions, that is ideal.”

Back at Krannert, the November Dance continues.

Cue the chimes once more.

Students make their way to a staircase, slowly again, their paths now intertwined, moving as one. The audience takes to a surrounding banister.

The students tear black blindfolds from their eyes as they reach the top of steps leading down to the theater. Swiftly, their movement ends at folded sheets of large sketch paper in a row on the floor. Each unravels to reveal words and drawings pertaining to issues they felt most personally pertinent.

“Love.” “I Freedom?” “We Are One.”

They tear the papers to shreds – the visual equivalent to setting their words free. They don’t need to speak, their clothing and movement speak for them.

Becker stands at the top of the crimson steps, camera in hand, smile spread on her lips once more – her light eyes fixed on her students.

“I think that it’s there whether we acknowledge it or not,” said Becker twisting her rings. “For me, my class, in general, is all about giving people the information to make educated choices. We’re all participating in this every day, unless you’re naked in a closet sitting in your room, in which case you’re participating by not participating. You’re still in relationship to clothing all the time.”

Daring to experiment. Moving, changing, interpreting the world into wearable art. A constant conversation with culture. That’s the way fashion speaks. Becker has a unique ability to translate that text of design. Increasingly, it seems, people are listening.

Professor Becker’s spring Fashion Design course will host their 10th annual Re-Fashioned Fashion Show on May 7, at 7 p.m. in Temple Hoyne Buell Hall showcasing collections the students have produced for their final project.

About Shalayne Pulia…

Shalayne is a senior journalism student at UIUC with a passion for the cultural arts. She hopes to move to New York City upon graduating to pursue a career in lifestyle magazine writing.

About Shalayne Pulia…

About Shalayne Pulia…