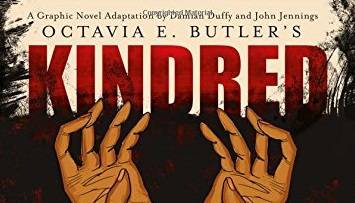

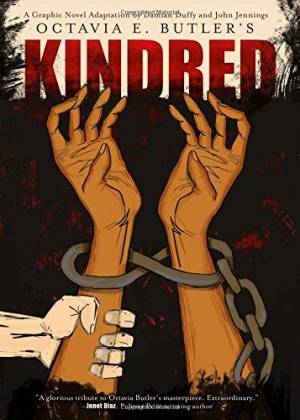

Everything about this new graphic novel enticed me: from the infinity symbol on the cover, to endorsements from two women whose talent I respect (Junot Diaz and Nnedi Okorafor), to hometown pride of the men who adapted it. But for everything that drew me to it, I was slightly fearful, the same way I am whenever there’s an announcement that a film will be made of one of my favorite books. Although my Midwestern heritage identified solidly with my first sci-fi love, Ray Bradbury, there are things that only another woman could articulate for me, and I found them in Octavia Butler’s heroines.

In Kindred, two writers in California in the seventies find each other and marry. One day, the woman, Edana (or Dana for short), feels dizzy and finds herself displaced in time and space. The experience repeats itself, always returning her to a plantation in Maryland pre-Civil War, whenever a particular ancestor of hers finds his life in mortal peril. Her ancestor, Rufus, is the white son of a slave owner, and she is a black woman who has just lived through the Civil Rights era. When her white husband, Kevin, accidentally joins her, it makes life a little easier, but also more confusing. Each time she returns, the situation grows more intense, and the plantation even begins to feel like home. Neither pure time-travel fiction nor slave narrative, Kindred explores racial issues from each side but also examines the feeling of being a non-person, and the ridiculous impossibility of an experience that seems unbelievable yet actually happened.

John Jennings communicates so much about the text and characters’ feelings with his palette choices that Damian Duffy can focus primarily on dialogue, without having to spell out every internal thought or exposition. Through the use of color and vibrancy, it’s easy to distinguish Dana’s memories from her reality, and it’s immediately clear that she sees her time-travels as more “real” than her California life when she looks back on this adventure. Even small style choices, like choosing to outline specific details in white as well as – or sometimes instead of – black, create an urgent feel within the images, pressing me through to the next and next panel and making my heart race. Still, I took in the details and absorbed the story, the place, the feel as I read, especially due to the astutely-rendered expressions on each character’s face. And don’t breeze past the full-leaf chapter breaks; these illustrations are ones that I could gaze at for hours.

John Jennings communicates so much about the text and characters’ feelings with his palette choices that Damian Duffy can focus primarily on dialogue, without having to spell out every internal thought or exposition. Through the use of color and vibrancy, it’s easy to distinguish Dana’s memories from her reality, and it’s immediately clear that she sees her time-travels as more “real” than her California life when she looks back on this adventure. Even small style choices, like choosing to outline specific details in white as well as – or sometimes instead of – black, create an urgent feel within the images, pressing me through to the next and next panel and making my heart race. Still, I took in the details and absorbed the story, the place, the feel as I read, especially due to the astutely-rendered expressions on each character’s face. And don’t breeze past the full-leaf chapter breaks; these illustrations are ones that I could gaze at for hours.

Duffy’s story keeps the dialogue as pure as possible, only a few times rearranging or paraphrasing speeches. Of course, the writer of a graphic novel also contributes to the pacing of the panels and how the story is told. Even though this is referred to as an adaptation, the graphic novel is almost 240 pages to the written novel’s 290; I was hoping that those 50 missing pages were primarily description, and this would be close to a one-to-one lift. However, Butler’s writing style is so direct that it did need to be condensed. While the story focused on the slavery aspects, preserving the themes of racial identity, non-entity, and privilege, some of the cuts made it obvious what was missing from this woman’s story: a woman’s perspective.

Duffy’s story keeps the dialogue as pure as possible, only a few times rearranging or paraphrasing speeches. Of course, the writer of a graphic novel also contributes to the pacing of the panels and how the story is told. Even though this is referred to as an adaptation, the graphic novel is almost 240 pages to the written novel’s 290; I was hoping that those 50 missing pages were primarily description, and this would be close to a one-to-one lift. However, Butler’s writing style is so direct that it did need to be condensed. While the story focused on the slavery aspects, preserving the themes of racial identity, non-entity, and privilege, some of the cuts made it obvious what was missing from this woman’s story: a woman’s perspective.

Kindred is a story about owning people, about treating them like property, about disregarding them as human. It is definitely about how white people treat blacks, but it is also about all those things as they apply to women. On the plantation, treating slave women as property is expected; that is in the definition. But even in her own time, Dana is ordered around and invalidated by her husband, who began his first conversation with her by early-era negging. Something that was edited out of this version, however, is a five-page conversation where Kevin rejects the evidence of his own eyes and repeatedly tells her that she is incorrect about having traveled back in time after her first trip. In fact, there are several ugly passages from the book where Kevin disbelieves, invalidates, or ignores his wife’s reality which aren’t included in the graphic novel. The husband’s character in this version has the appearance of an open and supportive character, when in the book he is a gentler reflection of the plantation owner, unintentionally treating Dana like less than him.

Kindred is a story about owning people, about treating them like property, about disregarding them as human. It is definitely about how white people treat blacks, but it is also about all those things as they apply to women. On the plantation, treating slave women as property is expected; that is in the definition. But even in her own time, Dana is ordered around and invalidated by her husband, who began his first conversation with her by early-era negging. Something that was edited out of this version, however, is a five-page conversation where Kevin rejects the evidence of his own eyes and repeatedly tells her that she is incorrect about having traveled back in time after her first trip. In fact, there are several ugly passages from the book where Kevin disbelieves, invalidates, or ignores his wife’s reality which aren’t included in the graphic novel. The husband’s character in this version has the appearance of an open and supportive character, when in the book he is a gentler reflection of the plantation owner, unintentionally treating Dana like less than him.

It’s a crucial element of this story, and by erasing it, Jennings and Duffy missed a big part of the theme. To be telling the truth and disbelieved by someone who loves you is excruciating, bordering on betrayal. Feeling those things as I read the original not only validated my experiences as a woman, but it helped me empathize with Dana’s experiences as a modern woman forced into slavery. Its lack left a noticeable crater as I read the adaptation, leaving me feeling like telling the authors the same thing Dana said to Kevin when he was trying to deny minimizing their situation, “You are. You don’t mean to, but you are.”

Octavia E. Butler told amazing allegorical tales that drew parallels to societal problems. One of those problems was the ingrained male response to question, deny, and invalidate women’s experiences, and that problem persists today – just ask any Sad Puppy, GamerGate defender, or rapist who gets a “boys will be boys” sentencing. To gloss over this issue is understandable, since both Duffy and Jennings are men, but it makes this version of Kindred less powerful for me.

Their adaptation does an amazing job of reproducing the plot and characters. It’s a wonderful read for any fan of science-fiction, historical fiction, or issue-driven stories. Readers who go in for the gorgeous stand-alone graphic novels like American-Born Chinese or Kill My Mother will absolutely love owning this book. And I will go buy it, because it is beautiful and beautifully told, and I will shelve it next to my copy of the original. Together, both works deserve to be appreciated and cherished.