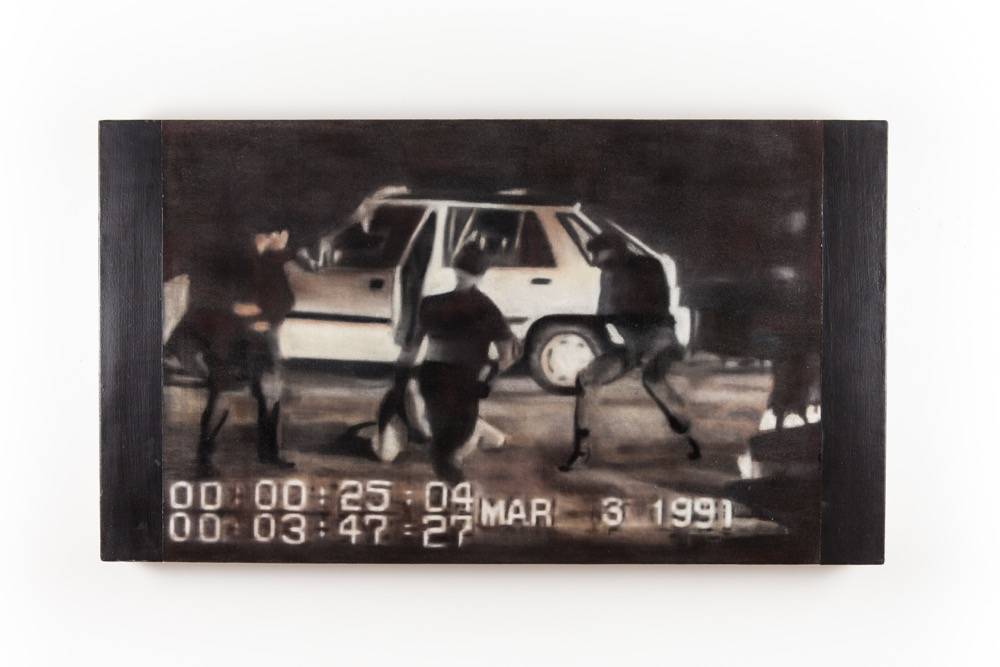

In the past several years, there has been a heightened focus on the circumstances of the deaths of African Americans during altercations with the police. Social media, and the general news media, has found a new immediacy due to how capable smartphone and internet-enabled device technology have become. This has created a societal transparency, specifically within the African American communities, centered around the ongoing violence concerning the police and the people in the community. These interactions are now being recorded and reported in minutes instead of overnight. But there should be no assumption that this new ability, creating more visibility, is depicting something new or anomalous. There is a particular repetition. These negative interactions, between these two defining American cultures — throughout American history, seem to correlate, period to period. I would like to examine this.

“I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races, [applause] — that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race. I say upon this occasion I do not perceive that because the white man is to have the superior position the negro should be denied every thing.”

“Our new Government is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and moral condition.”

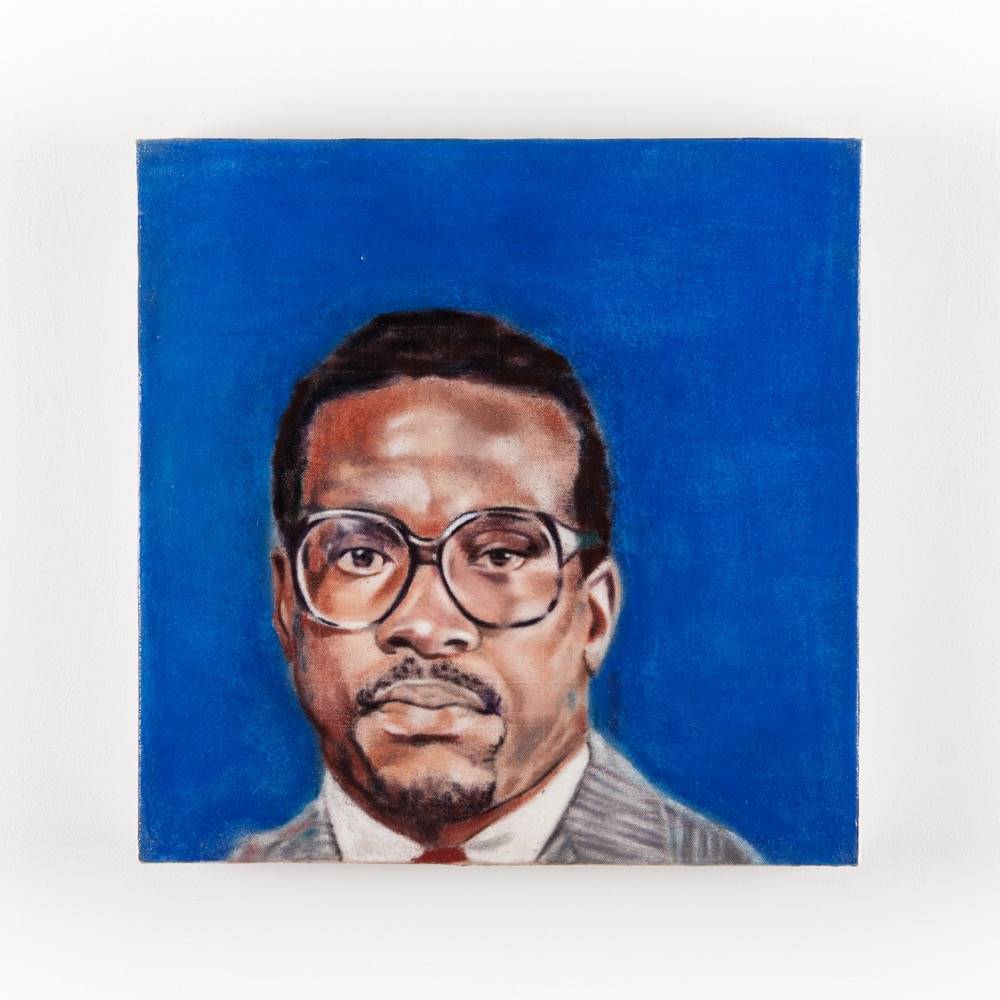

Another questionable reality in America is the disparity between the percentage of White police officers and the amount of African Americans in the communities they work in. In 1860, out of all the “deep” south states, Texas was the only state that’s slave population had less than 40% of over all population(30.2%). South Caroline and Mississippi were the two states where slaves were the majority (57.2% & 55.2%).It would be unscientific to out-right say that this is a direct correlation to the population ratio during slavery. But it is an unsettling mirror image, in how the division of power has been historically laid out in the United States. To me there is a lack of awareness and an overall acceptance of police departments with officers who are predominately White, working in an area they do not live in and a culture they are not a part of. Imagine if Madison, Wisconsin, with a population that is 79% White, had a police force that was predominately Black. Shouldn’t we wonder why the opposite is common and isn’t perceived as strange?