Art is beyond powerful.

Art, in any form, has the potential to reflect contemporary social reality and to promote social revolutions. On an individual basis, artists have the unique ability to step within their creative works, and therefore exit out of their individual lives for a while. Depending on one’s circumstance, escapism can be advantageous.

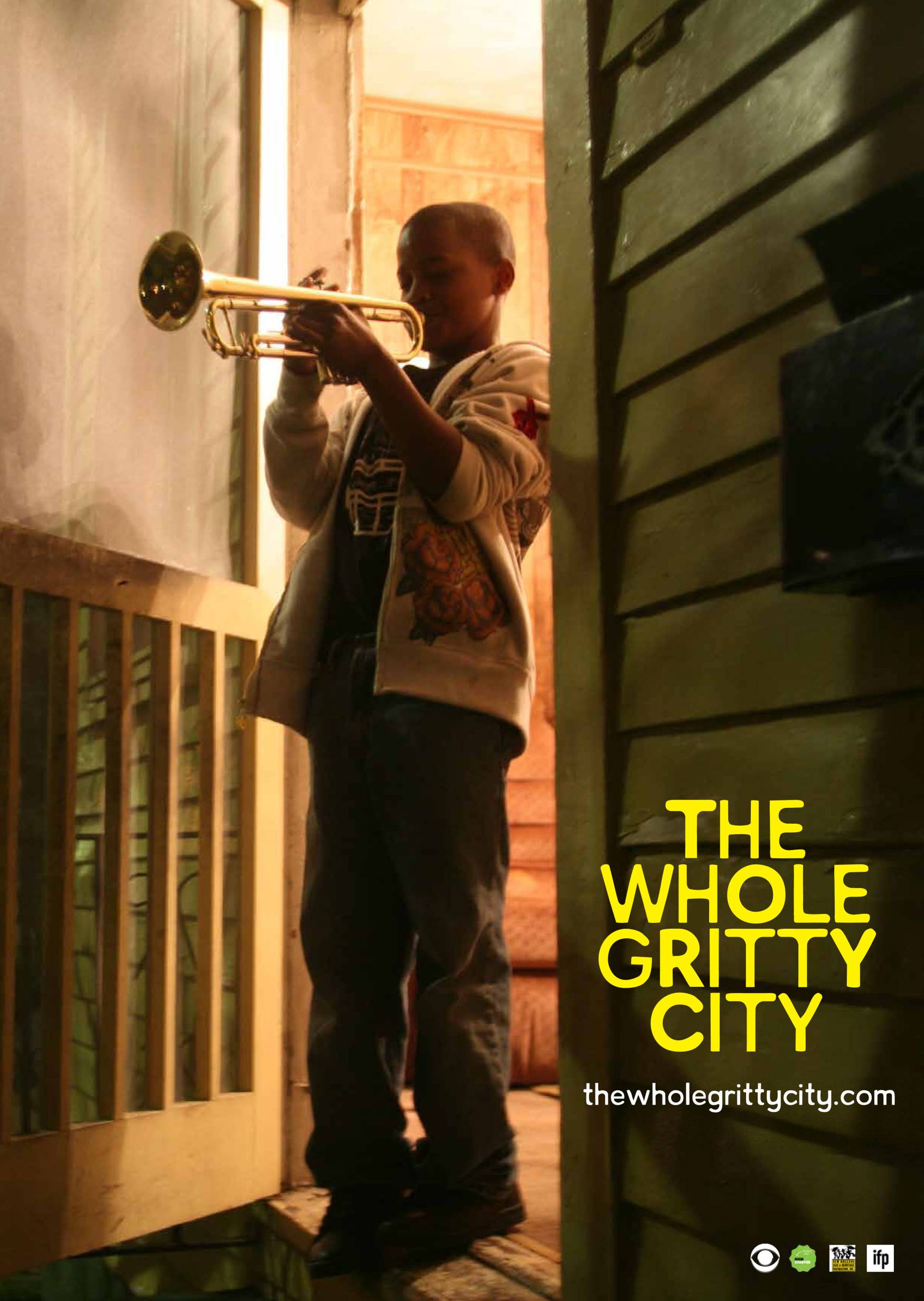

Last week, the University YMCA hosted a showing of The Whole Gritty City at the Art Theatre and subsequently held discussion about the film. The documentary follows three New Orleans marching bands, aged from elementary to high school, in the wake of Katrina.

The documentary is, in some ways, twofold. It first forces the viewer to come to terms with the extreme difficulties that are in place for many students living in poverty, and then discusses the impact of music on these communities.

A trumpet player in elementary school named Bear took the camera on a tour around his neighborhood; he noted which street he did not like, because it had guns on it. He went on, later in the film, to tell the audience about the day his brother passed away from gun violence.

The assistant band director at one of the schools, Brandon Franklin also dies as a victim of gun violence during the shooting of the documentary.

This film is saturated with these legitimate references to family members, friends, and students who face this almost desensitized violence. It’s hard to watch.

Also apparent in the documentary is the way in which these marching bands function as an escape from the gang and gun violence and poverty that is otherwise pervasive in these students’ everyday lives.

Of course, quality art education programs are not a total or permanent solution for areas of extreme poverty. But I do believe that art education is beneficial everywhere, including these high poverty areas.

The impact of art education is therefore not specific to New Orleans, nor is it specific to marching bands. Art education everywhere insists that students interpret their world in a manner with which they may not be familiar. It encourages students to discuss society; what’s wrong with it and what’s good in it. Art is intricately tied with emotional intelligence. To really engage with any sort of art, you must broaden your emotional capacity.

Finally, to engage in a more logistical argument, students who study art are, statistically speaking, more likely to perform well in academic subjects than their counterparts. We know all of this, and yet music programs across the country are facing under-appreciation and potential budget cuts, especially in Illinois.

In 2010, when the Champaign School System needed to cut its budget, the first thing proposed to be reduced was the music programs. Lucily, due to community uproar, the programs were retained and restructured. With more cuts on the horizon, many are worried about how Governor Rauner’s proposed budget will deal with art education, both at a local and university-wide level — with massive cuts to state-supported arts programs threatened.

Nationally, art programs are underfunded. Federal funding for the arts and humanities receives about $250 million per year, compared with the $5 billion that is supplied by the National Science Foundation. Our society overwhelmingly prefers STEM fields when thinking of the ideal public school curriculum.

Yet art is an immeasurably large component of what endows our societies with their culture. Without culture, there isn’t a point to any of this. Rather than defunding art education, in any degree, we need to actively and academically train the next generation of artists.

Our society must come to terms with the immense significance that art education has for the cultural, but also intellectual, health of our nation and various communities.

It seems like forever that we, or at least Western society, have valued reason over emotion. For that reason, among others, we value “academics” over the arts. It’s time that we reconsider the validity of that hierarchy.

Photo by The Whole Gritty City film.