Last week, I attended the Documenting Inequality exhibition at the Krannert Art Museum—all of the artwork was the result of a project of University students enrolled in a Grand Challenge Learning Course. Pieces in the exhibition documented issues regarding gender prejudice, racism, and heterosexism through visual artwork and documentaries.

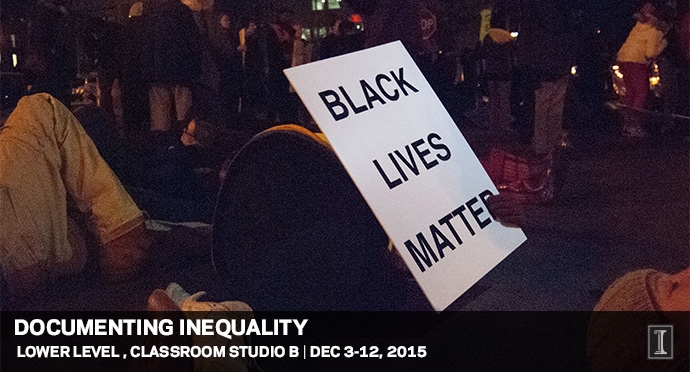

Some of the projects focused on discrepancies in equality on campus—interviewing students about the prejudice they’ve faced as a woman in a STEM field, as a racial minority, or as a person within the LGBT community. Other projects examined national issues, most commonly the Black Lives Matter movement.

It was powerful and disturbing to watch old news clips discussing the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland and others—the number of black lives lost in encounters with police over the past several years has become too long to list in an opinions column.

It was equally compelling to put on a pair of earphones and listen to stories about heterosexist discrimination. And, perhaps, particularly because I am a woman, I was gratified to see projects focusing not only on the existence of sexism, but also on the prevalence of the practice—particularly in our supposedly post-feminist society.

But what stuck me most about the exhibit was the essentiality of keeping up momentum in protesting these forms of inequality.

In the exhibit, I spent a lot of time reflecting on the effects of sociological privilege—particularly that of white people, men, and those who identify as straight. In one of its many definitions, privilege is the luxury of not having to continually care about a given form of inequality because it does not directly affect you.

Perhaps the most frightening aspect of this concept is the possibility that it can result in widespread apathy for issues of inequality. It can be, admittedly, difficult to continue to passionately protest an issue when the media coverage dies down.

Invoking apathy is how we tend to deal with the ugliest parts of life. And to an extent, apathy is necessary in guarding against hopelessness and depression, but it can also be dangerous.

It’s disconcerting to imagine that the Black Lives Matter movement is becoming hackneyed in our minds, but that is exactly what may be happening. The more we hear about black deaths at the hands of white policeman, the more the practice is perceived as a normalized phenomenon. There is a related and unfortunately prevalent belief that now, following the marriage-equality ruling, the issues regarding injustice and the LGBT community have all been remedied.

Further, I believe that sexism has been underrated and normalized for a long time now—to the point at which my friends and my family have told me they don’t believe in the existence of gender prejudice anymore in this day and age. I’ve been told, as recently as a few months ago, that a feminist is nothing more than a complainer.

We cannot accept this degree of apathy or scapegoating to avoid dealing with issues of inequality, which is precisely why projects like the Documenting Inequality exhibit are so imperative to this “new civil rights” historical moment.

These sorts of projects serve as an important reminder—especially for those in privileged social groups.

We need to continue writing about these issues, talking about discrimination, participating in protests, and educating ourselves about forms of prejudice.

Racism, sexism, and heterosexism—and especially the violence attached with each ideology—are not social realities that we can deem acceptable simply because they are prevalent. Continued instances of these prejudices should, ideally, make us more apt to protest rather than contributing to our idea of what is normal.