Last week, the Champaign City Council held a study session on the “Use Of Technology To Address Violent Crime.” The study session was led by the Champaign Police Department, which asked for tens of thousands of dollars of funding to acquire surveillance cameras, automated license plate readers, and gunshot detection technology. Before the meeting, council members were provided with a 20-page memo that outlined CPD’s case: what it’s asking for, where and how technology is planned to be deployed, and the cost.

As we’ve previously written, addressing gun violence is complicated and will require myriad solutions that must be continuously evaluated. We are not convinced that a mass surveillance of our Black, Brown, and poor neighbors is one of those solutions. The city council must offer public feedback sessions before approving the deployment of these technologies.

We cannot recount each and every idea and comment from each councilperson, but we encourage you to watch the entire session online. It’s long, and yes, even boring, but can provide you with the specific comments your elected representative(s) provided. In brief, the study session can be summed up in the following asks from the Champaign Police Department:

- Five surveillance cameras, $17,740 (these would be publicly marked)

- One mobile video trailer, $34,291

- One investigative camera, $5,050 (this would be covert and unmarked, to be used in investigations)

- 36 Automated License Plate Readers (ALPRs), $99,000 for the first year and $90,000 for the second year

- Gunshot Detection Technology (GDT) to be used to monitor the Garden Hills neighborhood, free for the first year

- The ALPRs and the GDT would be acquired through a lease with Flock Safety, an Atlanta-based company founded by two white men. The GDT would be free for a year, a bonus add-on to the lease for the ALPRs. CPD was not initially interested in GDT; it was added on to this memo when Flock offered it for free.

There were two votes: one for pursuing the cameras and ALPRs, and one for pursuing the GDT. Davion Williams (District 1) was the only no vote on the ALPRs. Alicia Beck (District 2), Michael Foellmer (District 4), and Williams were the only no votes on the GDT. As a whole, the council voted the measures out of the study session, and will take a proper vote on them at a future meeting.

Residents of Champaign — this editorial board included — have been calling for elected officials to do something about the massive uptick in shooting incidents and homicides this year. The comments from city council members generally seemed to reflect the tension between appearing to do something and appearing to do nothing; the frustration and resignation among city council members was palpable. Almost all of the city council members expressed concern about creating a surveillance state, and the liabilities of this sort of data being stored on the servers of the company from which the ALPRs and GDT are leased. But in the end only one member voted against the cameras and ALPRs and three against the GDT. The council seems eager to demonstrate they are “doing something,” but is that something the right thing? That something — increased surveillance in parts of our community — was presented by the Champaign Police Department, not the city council members or the various organizations working to make change.

Let’s step back and consider what has been proposed.

Currently, CPD relies on private camera footage from the security systems and Ring doorbells of residents to conduct some of their investigations. In that regard, it seems to make sense that CPD should have their own cameras and their own footage. Per the memo, these cameras would be in public spaces and record video only, no audio. There wasn’t much discussion among city council members about the cameras; there seemed to be a silent approval of that component.

Do surveillance cameras prevent crime? Probably not all that much. Is that type of footage helpful in solving crimes? Certainly there is an argument to be made for that, but video evidence is not a simple recording of life or an arbiter of Truth™. It’s a tool that must be implemented by humans, who are all flawed and subject to biases. They are expensive, and require regular assessments of their efficacy.

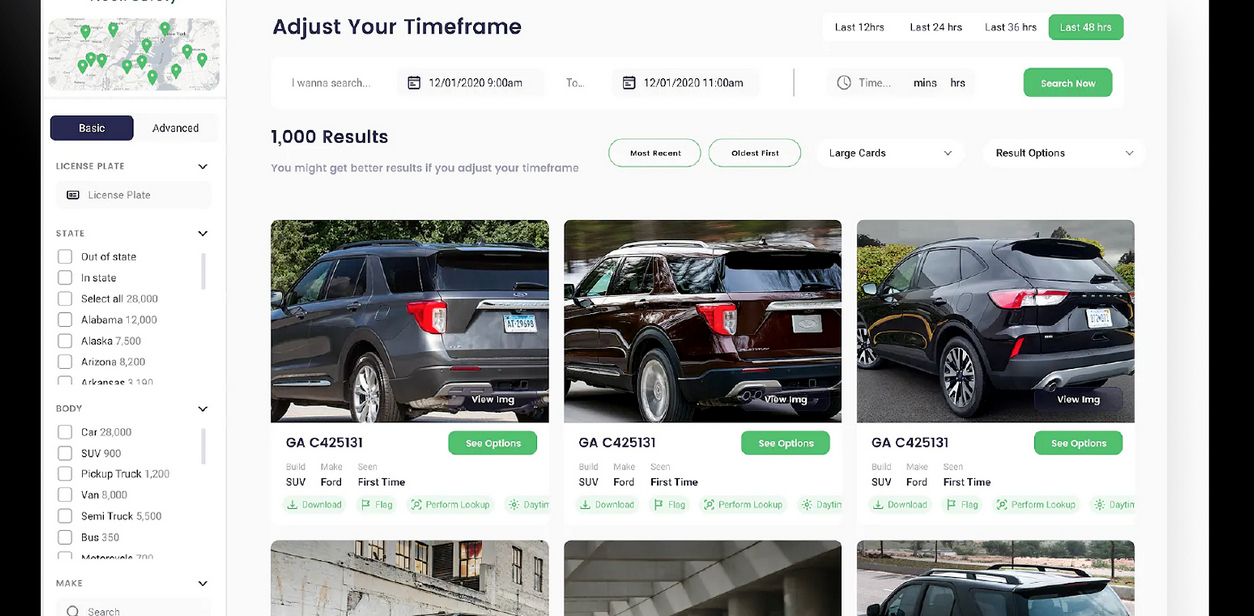

Most of the discussion was about the use of ALPRs and GDT. The ALPRs use photos to capture license plates. These photos also include partial images of the cars — enough to determine make, model or body type, and color — but allegedly do not capture images of the car’s occupants. These images are stored on Flock’s servers for 30 days, and can be downloaded and entered into evidence (where appropriate) by CPD. The database is searchable and can be shared with other Flock ALPR users, like the Peoria, Rantoul, and Springfield police departments, for instance. These license plate readers would be placed on “arterial roads” as well as in neighborhoods of interest. The exact locations haven’t been shared, but the map below can offer some guidance.

Screenshot from “Use Of Technology To Address Violent Crime” Champaign City Council Study Session memo.

CPD stated that they don’t have intentions to use ALPRs to go after violations like overdue registrations and obscured license plates. CPD noted that it could be used to monitor traffic, especially during large events like the Illinois Marathon. There was some discussion about FOIA requests — for example, a request for all images on a certain road for a duration of time — and those requests would likely have to be filled, unless they can scoot around the law under the undue burden clause. Driver registration is not something that would be shared.

Flock’s GDT is not the same technology as ShotSpotter, which has been in the news recently for the troubling consequences of its use, among which are the targeting of Black and Brown neighborhoods and audio surveillance. According to the Flock representative at the study session, the company’s GDT is different from ShotSpotter because its “devices [look] for specific sound wavelength” and doesn’t incorporate a human element. When asked by Beck about the proprietary algorithm and whether or not it is shared with lessees, he said that there was no algorithm and that he didn’t know if it was shared with lessees. In short: He didn’t seem to know how the technology works.

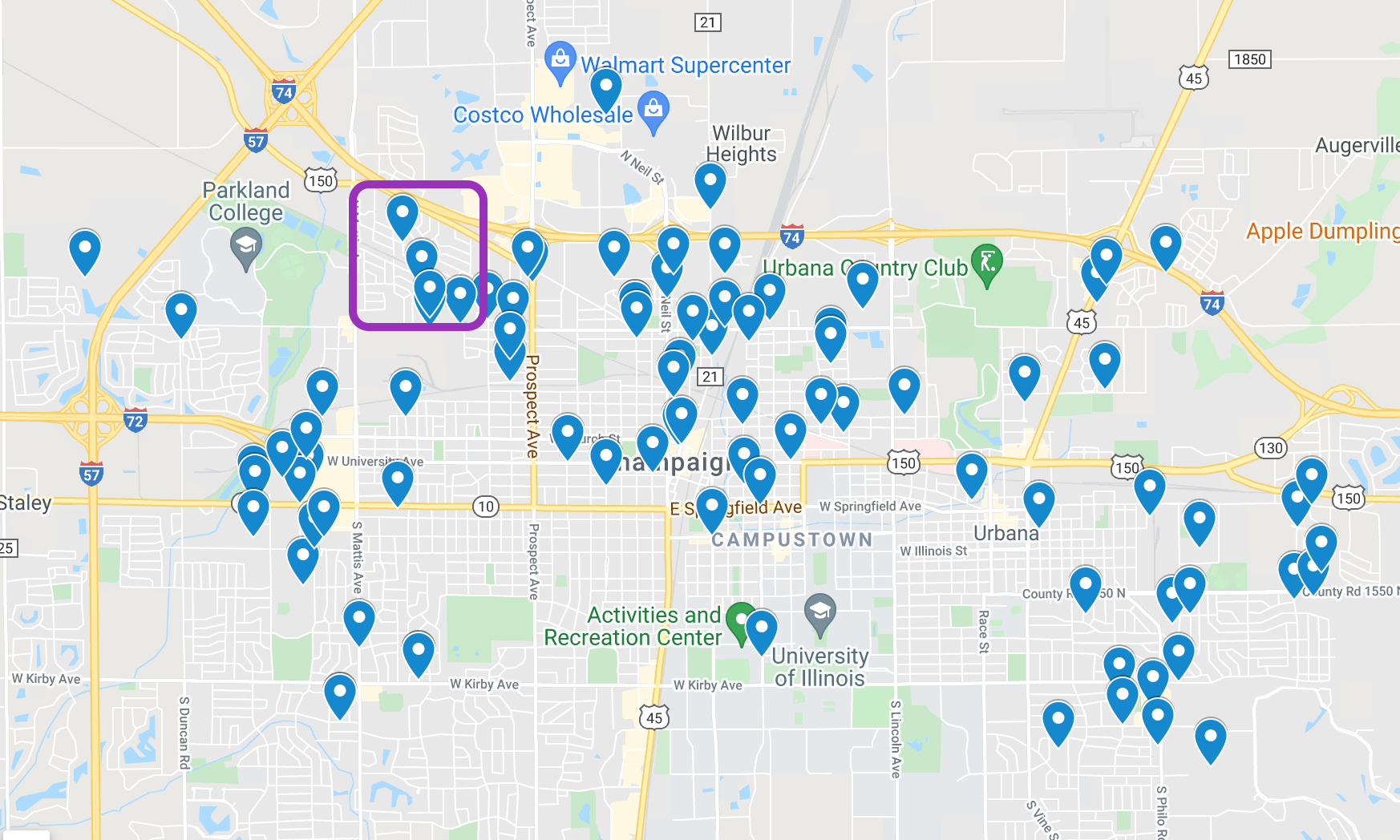

CPD had not planned on including GDT in this request, but when Flock offered the technology to surveil 1.3 square miles for free for one year, CPD added it to the memo, with the intention of utilizing this technology in the Garden Hills neighborhood, conveniently also approximately 1.3 square miles. The area from Bradley and McKinley, Mattis and Bradley, Bloomington and Mattis, and Bloomington and McKinley would have acoustic receptors that allegedly triangulate gunshots to a one meter area of origin. We know from all the CPD press releases and reporting that gun violence and homicides are not limited to the Garden Hills neighborhood.

“Gun violence incidents showing both injuries and killed were downloaded for Urbana and Champaign January 1, 2021 – October 12, 2021 from the Gun Violence Archive. Data may be incomplete. Pins are based on block information such as the 1000 block of Main Street and do not denote the specific address for where the use of a gun was recorded.” Champaign’s Garden Hills neighborhood, an historically predominantly Black neighborhood and the proposed Gunshot Detection Technology monitoring area is outlined in purple. Screenshot from Google Maps (by Gun Violence Archive). Garden Hills demarcation added by Smile Politely.

The scholarly research about GDT has mainly been focused on ShotSpotter technology, which, according to Flock, is not the same as Flock’s “Raven” system. However, the research shows that implementation of GDT has a whole host of problems, and does not necessarily prevent gun violence. How different is Flock’s proprietary system from ShotSpotter? Should we be investing in a technology that isn’t well researched?

In final comments, council member Beck noted that we are working on “building a fence around our Black and Brown communities — a fence of technologies.” These interventions — and the people advocating for them — are explicit in saying who and where will be monitored. It is an historically and predominantly Black neighborhood and its Black male residents who will be surveilled by an institution (the police) developed to keep Black people in a certain place, behaving in a certain way.

This gun violence is not new, but it is worse than before. The lack of opportunities plaguing our Black and Brown and poor neighbors is not new, but the pandemic has exacerbated things. Now that gun violence has trickled into whiter and wealthier neighborhoods and commercial districts we, as a community, are demanding action. But at what cost? In addition to the more than $156k CPD is requesting for surveillance equipment, is there a budget to consolidate and properly fund the intervention groups working with people in the community? Will CPD incorporate a rigorous evaluation process for these technologies, at 6 month and 12 month intervals? Will we hold them accountable?

As we’ve said many times before, there is no simple solution to this problem. It’s complicated and requires multipronged, complicated solutions. There has been great loss and trauma, but that is not reason enough to forfeit civil liberties and the challenging, rigorous discussion needed to push and compromise to arrive at meaningful change. We cannot simply allow CPD to offer militarized interventions, which are inherently racist, classist, and antagonistic. As one public commenter said, it’s time to think outside the box.

The Editorial Board is Jessica Hammie, Julie McClure, Patrick Singer, and Mara Thacker.