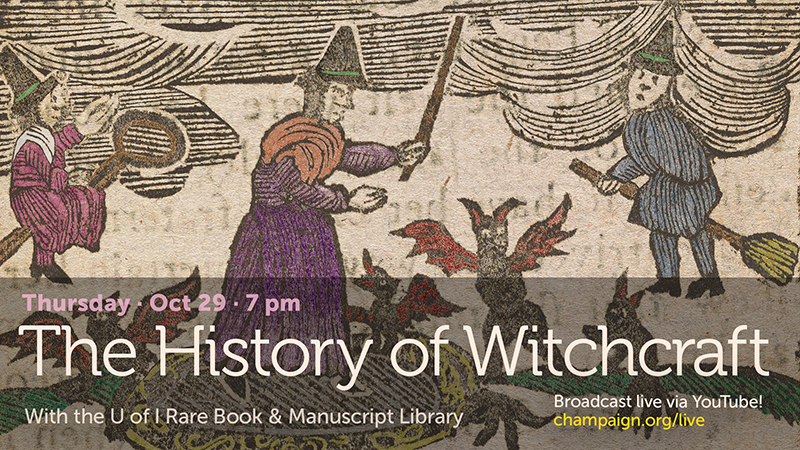

Whether you’re talking about TV programming, costume trends, or the appearance of interviews with practicing Pagans in “muggle” news outlets, October is clearly the season of the witch. And thanks to two supernaturally-smart scholars at the Illinois Rare Book and Manuscript Library (RBML), on the eve of Thursday, October 29th, over 51,000 attendees from around the country will be treated to a virtual look at some of the oldest texts documenting the real history of witchcraft.

Presented by Cait Coker, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts, whose research interests focus on “the roles of women in the history of publishing, as well as how that intersects with popular culture” and Ruthann Miller, Visiting Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts, whose research interests include “the supernatural aspects of the medieval period in Europe,” this event offers a rare opportunity to explore early representations of witches and witchcraft and they can tell us about issues of religion, sexuality, power, violence, and the victimization of women across the ages.

I had the chance to connect with Miller and Coker to learn more about this fascinating event. Their combined knowledge and excitement made for a most magical conversation. Find out the texts they’ll be showcasing, and get their takes on the Witch Trials and our culture’s endless obsession with witches and their craft.

Smile Politely: How did this event, and the collaboration with the Champaign Public Library, come about?

Ruthann Miller: Cait [Coker] and I have been working on reaching out to the Urbana-Champaign community to build better ties with non-university affiliates. We feel it’s really important for our community to know that the RBML exists as an institution for everyone and not just University of Illinois or other universities. We contacted the Champaign Public Library with this idea in mind and they were equally excited to participate in a collaboration between public library and public university.

SP: What aspects of the “The History of Witchcraft?” will you be covering?

Miller and Coker: Our talk will cover Western European witchcraft from the 1400s-1700s with a bit of historical background and modern popular culture parallels.

SP: From what we’ve discussed earlier, the majority of manuscripts that will be referenced are from the 1600s. What genres do they cover? I’ve noticed several in the “how to identify and stop a Witch” category. What can you tell us about the authors and their goals in writing these texts? Like many histories, the stories of the accused are told by the accusers. I would imagine that documents from the victims would be rare at this time, especially since hedge witches, midwives, wise women of the time held to an oral tradition and kept their knowledge hidden?

Miller and Coker: The popular perception of witchcraft during this period definitely influenced the genres of material that were published; items including both theological tracts and popular reports of trials. Materials relating to trials usually include transcripts between the accused and the accusers, but the likelihood of that being a mediated record is incredibly high; we need only watch news reports to understand how easy it is to coerce false confessions from people on the margins of society. You’re very right that the voices of midwives and herbal women seldom are heard first hand from period documents, but that’s also a function of centuries of recordkeeping in which the writings of the elite are maintained at the expense of those of every day people, which is something contemporary archivists are also thinking about as they strive to document modern happenings like life during COVID and the BLM protests.

That’s another thing we’re thinking about with events like these which reach out to the public

community is how those resources that can be read as “elite” are in fact there for everyone.

SP: Are they all part of the permanent collection? If not, how did they find their way to Champaign-Urbana?

Miller and Coker: Yes, they are all part of the RBML’s holdings.

SP: I’ve had the pleasure of attending several of the RBML’s in-person events and am curious to know what it was like putting this together as an online event. I believe there may be both advantages and disadvantages. What has your experience been like?

Miller: When we initially reached out to CPL, the idea was to collaborate on a webinar using Zoom and we anticipated about 50-75 people would be in attendance (this is typically what we see at in-person events). We published the event on a Thursday. Over the weekend we all had a hurried conversation about reaching the Zoom meeting capacity of 100 participants, which is when we switched to the webinar version of Zoom, which can accommodate 500. By Tuesday, we had 500 registered participants and we currently have about 51,000 people interested in attending on Facebook. At that point, we started talking about live streaming. Now, the event will be live streamed to CPL’s YouTube as well as Facebook (hopefully) and we will be uploading a recorded version to RBML’s and CPL’s YouTube shortly after the event.

Coker: We can’t serve cookies to people who aren’t here.

SP: Speaking of advantages, this online event has attracted interest and registrations from thousands of people worldwide. It’s wonderful to be reaching so many people. Were you surprised by this? How will that impact the event?

Miller and Coker: We are blown away by the response! It’s incredible. It really goes to show the ongoing impact that libraries of all kinds really have on their publics, particularly in trying times like these. We hope that those who tune in, in whatever fashion, not only get to enjoy what we hope will be a fun talk but will be able to think about what libraries doing for people in building online programming like this when we can’t all be together.

SP: To me, the record-breaking interest in this event also underscores our culture’s long standing fascination with witches and witchcraft, and not just during the Halloween season. What are your thoughts?

Coker: I think it kind of goes to show what our current preoccupations are with women, actually. The #MeToo movement of the last few years has really underscored the difficult lines of society’s power and ability to cover up the victimization of women in terrible ways. During these periods women were not able to speak for themselves and so we as historians have to go back and look at what happened with records that we know are problematic.

Miller: I think the fascination with witches and witchcraft that is so popular in our fiction and

television right now has made knowledge of it more mainstream and acceptable. Nonetheless, libraries, especially school libraries for K-12, can still face challenges to the material they carry from anxious parents. This was something that came up often as the Harry Potter series was being published — parents of students who thought the stories of fictional witches and wizards was scary or problematic. (Never mind that they celebrate Christmas in each book as well!) And now of course, J.K. Rowling has proven herself to be incredibly problematic and offensive in terms of some of the things which she believes. Having grown up reading those books, which practically inspired an entire generation to read, I think that messages of acceptance and of disseminating knowledge are more important than ever.

SP. In many ways the 21st Century pop culture obsession with the supernatural seems to mirror the witch-mania of the 17th century that led up to the Witch Trials. The main differences would be the existence of science and the feminist movement. What are your thoughts on this? How do the texts you’ll cover address this mania and/or the Witch Trials?

Miller: I think something to be careful about is projecting modern ideas onto historical events and individuals. There wasn’t a concept of “feminism” in the seventeenth century per se, although certain women writers of the period (like Margaret Cavendish, for example) certainly had some feelings on society’s inequalities with regards to gender and so on. But these women were by no means what we would identify as feminist in our current context because cultural attitudes towards everything — like government, class, religion — were so very different from ours.

Coker: I think there’s a reason we refer to “the Communist witch-hunts” of the 1950s — this idea of really persecuting people in frightening ways with little real evidence or even with manufactured testimony. I think a closer analogy might be the “Satanic panic” of the 1980s, especially with Dungeons & Dragons, but at the same time these weren’t things that killed thousands of people and so comparing the two to historical witch trials is inaccurate. With regards to the topic of science in the 17th century, there were certainly the beginnings of empirical knowledge investigation and experimentation, albeit limited by the technology of the period. For example, the famous plague doctors’ costumes with the flowing robes and the bird masks were designed to be the equivalent of all-purpose Hazmat suits: if the plague

was transmitted through the air, then the long “beak” of the mask stuffed with herbs would prevent it; if it was transmitted through “the evil eye” then the glass over the eye-holes would be a barrier; if it was transmitted through bodily fluids then the long robes and gloves would protect the wearer. They were trying so hard to be thoughtful in protecting themselves and investigating the causes that you can compare it to some of what’s happening right now and think, hey, people in the seventeenth century were doing as well as or maybe even better than we are in some ways! I also think contemporary pop culture’s obsessions are indicative of the things that have proven to be sensationalistic in all periods: sex, murder, and weird happenings. We humans love all of those things!

SP: What surprised you most in studying these texts? Did they impact your understanding of the era? If so, how?

Miller: For me, it was the amount of sexual undertones that run through almost everything relating to accusations of witchcraft. I knew that the main accusation for many was Devil worship, participation in the Sabbat (witch parties in the woods), and/or cavorting with demons, but so much is tied to actual “relationships” with the Devil and demons.

Cait: For me it’s seeing the constant through-lines of politics that are interwoven with all the

sensationalism. The Wonderfull Discoverie of Witches in the Countie of Lancaster (1613) was

dedicated to Thomas Knyvet, who was credited with apprehending Guy Fawkes and preventing the Gunpowder Plot that would have assassinated King James and Parliament in 1605. King James was famously anxious about witches and wrote a book about them called Daemonologie (1597), and this well-known obsession was what would influence Shakespeare’s witches in Macbeth. But some contemporary historians now question the evidence of this plot and posit that it may have been a manufactured political gambit with shades of shock doctrine. So now you have a combination of one of the biggest witch trials, possibly the most famous fictional witches, and the very real case of an insecure king trying to consolidate his power. That’s…a lot!

SP: Many of the victims of the Witch Trials were women of knowledge, herbalists, healers, etc. From a feminist perspective, one might say that their “power” was seen as a threat to the Puritan patriarchy. How do you, in this era, read those accusations?

Coker: You’re not wrong although it is something that pre-dates the rise of Puritanism by a few centuries, even if that’s what we most often think of (and we’re in America with its legacy of the Salem Witch Trials, so it does make sense!).

Miller: There are some modern scholars who argue that one of the major underlying factors in the witch trials was an attempt to prove the existence of God. Since witches were supposedly engaging in carnal relations with demons and the Devil, this meant they were corporeal and they actually existed. If demons and the Devil exist, then so too must God and the angels exist. Also, there is something to be said about the Church stamping out non-Christian belief systems.

SP: What are you most excited for attendees to see and learn?

Miller and Coker: We hope that attendees leave the webinar knowing that we have some pretty neat items in our collection and also that the library is open to them. There can be this barrier to special collections where people feel like we are too elite or “not for them,” but we really want people to know that we are open and rare books are for everyone!

SP: What do you think will surprise them the most?

Miller and Coker: That we have such phenomenally cool stuff in our collections, and that people can come see it when we re-open to the general public. As a state university, our library is open to members of the public to visit our exhibit gallery and to look at materials in our reading room.

SP: Do you have any recommendations for readers who may want to explore the history of witchcraft in greater detail?

Coker: I recently got a copy of Liz Williams’s Miracles of Our Own Making: A History of Paganism (Reaktion Books, 2020) which I’ve been making my way through. Pretty much anything by Ronald Hutton (who is maybe most famous for writing The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft in 1999) is going to be a masterclass on those topics.

Miller: For an older perspective, I recommend Jeffery Burton Russell’s Witchcraft in the Middle Ages (Cornell University Press, 1972). If you are interested in the demonolatry aspect, Walter Stephens Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex, and the Crisis of Belief (Universtiy of Chicago Press, 2002).

SP: Is there anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

Miller and Coker: People can log into watch our live broadcast Thursday, October 29th at 7 p.m. CST at champaign.org/live. A recorded version will also be available at the YouTube channels of both the RBML and the Champaign Public Library.

If you have questions about the RBML’s holdings, you can email all of the curators at

askacurator@library.illniois.edu. We’re really hoping those watching will enjoy this as much as we’ve enjoyed putting it together.

The History of Witchcraft

Presented by Cait Coker, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts

and Ruthann Miller, Visiting Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts

Thursday, October 29th, 7 p.m.

View the live broadcast at champaign.org/live.