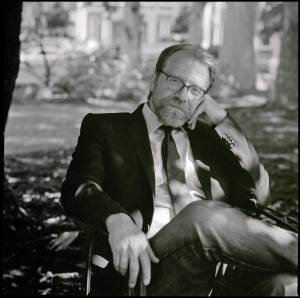

George Saunders is a MacArthur Genius who was just put on the shortlist for the Man Booker Prize for his most recent work, Lincoln in the Bardo. He’s also the headlining author of the PYGMALION Literature Festival, and I had a very pleasant chat with him about his appearance, his friends, and his amazing audiobook which features 166 unique narrators — most of whom are known persons. Although his accolades would entirely justify a conversation of East Coast academic intellectual-speak for me to grit my teeth through, I found Saunders’ demeanor to belie his Chicago upbringing, providing for an easy and open interview. I’m happy to share a portion in preparation for his appearance this Thursday, and can assure you that listening to him talk for an hour will be an enjoyable experience.

The following interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Smile Politely: You’re headling PYGMALION, which is not just a literature festival, it began as a music festival and expanded to other areas. I wonder if, in honor of the music aspect, your own guitar might make an appearance during your Thursday presentation?

George Saunders: It will not, I guarantee it. I love to play guitar but I’m just not that good; I don’t want to be that guy who foists it on everybody. I grew up on the South side of Chicago, and I’ve played since I was 13. I love it so much, but I have enough respect for it to know my limits.

SP: Well, on Colbert where I saw you play guitar (above, at the 7:00 mark), you said you had all this “overflow” from writing The Very Persistent Gappers of Frip, which is how you wrote those songs. Did you have anything like that after Bardo?

Saunders: What I did with this, I had that energy and I went right away on the road with the Trump campaign and wrote a piece for the New Yorker, then I wrote a TV pilot that we made for amazon. I channeled it in a different direction, I didn’t write any music at all. I was hyped up and said, “I have to get some projects,” then I just picked those two.

SP: A pilot?

Saunders: It’s for amazon and it’s called “Sea Oak” after a story in my book, Pastoralia. I’d written a feature script for it that never went anywhere, and in that moment after the Lincoln thing when I didn’t have any fiction going on, I just wrote a half-hour adaptation of that. Amazon was interested so we filmed it last spring in Brooklyn. It’s got Glenn Close in it and Jack Quaid and Rae Gray — another Illinois person — and Jane Levy. It’s directed by Hiro Murai who did Atlanta; it was so much fun. When it comes out, we’ll see if it’s good, and if so, we’ll get to make the series.

Saunders: It’s for amazon and it’s called “Sea Oak” after a story in my book, Pastoralia. I’d written a feature script for it that never went anywhere, and in that moment after the Lincoln thing when I didn’t have any fiction going on, I just wrote a half-hour adaptation of that. Amazon was interested so we filmed it last spring in Brooklyn. It’s got Glenn Close in it and Jack Quaid and Rae Gray — another Illinois person — and Jane Levy. It’s directed by Hiro Murai who did Atlanta; it was so much fun. When it comes out, we’ll see if it’s good, and if so, we’ll get to make the series.

SP: That sounds amazing, I look forward to it.

But going back to the event, even though there won’t be any guitar, can you reveal anything about your appearance? Will you be reading from Lincoln, answering questions…?

Saunders: I’ll definitely be answering questions, giving a talk, I’ll probably read from Lincoln although it can be a hard book to read from since it has so many voices. Sometimes, I’ve been reading sections of that, or sometimes we’ll get volunteers and we’ll read a little stage version. Or I might read another story. I tend to wait until just before to see what will be best for each audience.

Saunders: I’ll definitely be answering questions, giving a talk, I’ll probably read from Lincoln although it can be a hard book to read from since it has so many voices. Sometimes, I’ve been reading sections of that, or sometimes we’ll get volunteers and we’ll read a little stage version. Or I might read another story. I tend to wait until just before to see what will be best for each audience.

SP: I’ll fangirl a minute and say that the longer piece where the Reverend is talking about his experience almost in heaven, that part truly reached me. It would be amazing to hear you read it out loud in person*, but I’m torn because reading it to myself for the first time was such an important part of the book for me.

Saunders: That was a really freaky part of the book, I thought, “Oh, I can’t put that in, it’s too religious or too strange,” but in a way, the book built itself around it, saying, “Put me in the middle, trust me, put me right in the middle.”

SP: That was the part that made me turn the corner. It’s such a unique format that it took me a while to get into the book, but that’s the part that made me keep going.

The other thing that helped me through that was catching little clever references and jokes within the actual names of the sources you quoted. Were any of those real, or did you create them all?

Saunders: About 3/4 of them are real, I think.

SP: That’s odd, I thought for sure they were mostly your invention because I would find puns or just strange names that would make me laugh out loud.

Saunders: The funny thing is, the weirdest ones are the real ones. I tried, in my made-up ones, to not go too far because I wanted the readers to not be certain whether they were real or not. If I made up a bunch of crazy ones, then you’d say, “Oh, that’s a fake one.” It was a fun, elaborate game.

SP: Considering that, do you think that Lincoln in the Bardo fits the genre of historical fiction, or do you consider it more like speculative fiction?

Saunders: I think it’s like that old SNL skit where the man settles an argument by saying, “Hold it you two, it’s a dessert topping AND a floor wax.”

I’m comfortable with it being cross-genre. When I’m writing something like this, my only goal is to move you, that’s really it. I want you to read it as something that actually happened and be emotionally invested in it. That’s my only goal.

When I think that way about “what was Lincoln thinking that night?” I don’t actually care that much. Which I care about is making the reader feel like it’s happening right in front of her face.

SP: I’ve read that the first image in your mind for Bardo was of Lincoln holding his dead son’s body, in the crypt, and you pictured it as on a stage. Then you went on to write the book kind of as a play. I couldn’t help but notice the audiobook ended up being more like a radio play. I’m curious, did you satisfy your desire for theatricality with the audiobook? Or are you hoping that it will go on for theatre adaptation or film adaptation?

Saunders: We did sell it for movies, but yeah, from the very beginning it had that theatrical feeling. What I found was when I thought about it as a theatre piece and tried to write it — I think maybe it’s a working-class idea of what theatre is supposed to sound like — it was kind of lame. As soon as I said, “OK, forget that; it’s just a piece of fiction like I’m used to working on,” then suddenly it came alive and I could make it actually proceed.

I think growing up in Chicago, the road to literature was through performance. And even now, when I’m writing a story, I’m not actually reading it out loud but I’m hearing it in my head as a performed thing a little bit. That made it interesting to go into the studio and say, “Hey, this actually is like a play.”

But it is sold for movies, and I’m supposed to write it, so we’ll see if I can figure out how to do that or not.

SP: And it was sold to Nick Offerman, right? And Megan Mullally? Who were both on the audiobook. But you hear about things getting optioned all the time and such a small percentage ever actually get made… but this sounds like a pretty solid plan?

Saunders: That’s the plan. We’ve optioned that and are going to work together, figure out who might direct it and when I can write it. You’re right, it’s a real longshot, even if you option it to two great performers like Nick and Megan. But we all loved the idea and are kind of committed to not laming out, making the movie as weird as the book and using that medium to find some new angle on the story.

SP: That’s very cool. We’re big fans of them here; Nick, especially, has ties to C-U and a good relationship with this community. It sounds like you know them pretty well — did you get to work together while recording the audiobook, or was it everyone in their own separate boxes?

Saunders: Every single person recorded separately, there were no actors in the room at the same time. But I met them, I met Nick when he wrote a piece about me for his book, Gumption. We just got to be friends, and I called in a favor to ask if he would be Hans Vollman in the book, and I was just so grateful. Then he and Megan helped to connect us with some of the other actors who are in it. We didn’t actually work side-by-side but we did a lot of conspiring to get good people in it.

Saunders: Every single person recorded separately, there were no actors in the room at the same time. But I met them, I met Nick when he wrote a piece about me for his book, Gumption. We just got to be friends, and I called in a favor to ask if he would be Hans Vollman in the book, and I was just so grateful. Then he and Megan helped to connect us with some of the other actors who are in it. We didn’t actually work side-by-side but we did a lot of conspiring to get good people in it.

Some of my cast, I knew a little bit: Carrie Brownstein, Jeff Tweedy, Miranda July. It was really moving to see people step up to do it, just for the love of it, it was very meaningful.

SP: Are you actually reading my notebook over my shoulder right now?

Saunders: Yes, I am, it’s one of my powers.

SP: I was looking for a way to bring Jeff Tweedy into the conversation, because I read your NY Times article about Wilco’s “One Sunday Morning” back from early 2016, and I couldn’t help but notice what you wrote – that the song is “’about’ a father and a son, ‘about’ religious belief” — are themes also quite present in Lincoln in the Bardo. Was that song on your mind while you were writing, or vice versa?

Saunders: I actually listened to that song when I was finishing Lincoln in the Bardo. I would lose energy a bit and you know, you’ve read it so many times that you say, “Ugh, I can’t stand it anymore.” Then I would turn on that song and “Via Chicago” and some stuff from Sleater-Kinney and remind myself of what intensity feels like. I don’t know which direction they crossed: whether I liked it because it was about that or because of the book.

Saunders: I actually listened to that song when I was finishing Lincoln in the Bardo. I would lose energy a bit and you know, you’ve read it so many times that you say, “Ugh, I can’t stand it anymore.” Then I would turn on that song and “Via Chicago” and some stuff from Sleater-Kinney and remind myself of what intensity feels like. I don’t know which direction they crossed: whether I liked it because it was about that or because of the book.

The main thing is that I use other art forms to remind me how intense people are. You listen to Jeff or you watch Megan or Nick, and you see they are people who are really really living for art. Anybody who’s fully put their whole life into their art, it’s very useful to just be in the presence of their work, to remind yourself how serious this is. Art is not a hobby or something you should do lightly, it’s something you have to pour your entire being into in order for it to sit up and notice you.

You can’t phone in anything, you have to really bring your whole being here and work. Especially when it’s something you’re doing as “a job”, you can show up to the desk and be half asleep. Only half there. And I think that’s how you give your artistic power away: by treating it as a mundane thing instead of a sacred thing.

SP: Wow. I’m definitely quoting you on that one.

———

George Saunders will appear at the Colwell Playhouse inside Krannert Center for the Performing Arts on Thursday, September 21, at 6:30 p.m. The event is FREE, but guaranteed entry is not available — but there is a Waiting List that will help. Saunders hasn’t been to C-U “since High School,” he thinks, to see Boston at the Assembly Hall. Now that he’s world-famous, it might be that long again before he’s free enough to return, so I’d encourage going if you’re at all curious.

All images provided by and used with the permission of Blue Flower Arts.