The first time I saw Kim Curtis’ paintings, I knew I was going to love this assignment. Whoever made these pieces knows how to create striking images that are also open to the viewer’s interpretations. I love that in an artist. To be able to make a strong statement while also remaining flexible enough to be accessible is a great skill, and I was fortunate enough to talk to Curtis about how that skill is cultivated.

Smile Politely: What are your pronouns?

Kim Curtis: She/her.

SP: Did you grow up here in CU?

Curtis: I grew up in Los Altos Hills, California. It’s now central to Silicon Valley, but back then it was just middle class families living in a San Francisco suburb.

SP: How has your hometown influenced your work — or even your access to various forms of art?

Curtis: We grew up largely on our bikes or cutting through mustard fields to get places. I had a “long leash” because I was the last of four kids; it was the 70’s and it was a safe place to roam. Its proximity to Stanford University is ultimately what made the most artistic impact on me, in the form of my fantastic high school art teacher who was working on his PhD at the time. His name is Charles Garoian and he went on to run the Art Education department at Penn State. But back in the 80s, he was writing his dissertation and testing out a lot of his theories on us lucky public-schooled teenagers. He taught me Art History, Painting, Photography, and, since they didn’t have a Sculpture program, he helped me build an armature and guided me through my own sculpture projects.

Curtis: We grew up largely on our bikes or cutting through mustard fields to get places. I had a “long leash” because I was the last of four kids; it was the 70’s and it was a safe place to roam. Its proximity to Stanford University is ultimately what made the most artistic impact on me, in the form of my fantastic high school art teacher who was working on his PhD at the time. His name is Charles Garoian and he went on to run the Art Education department at Penn State. But back in the 80s, he was writing his dissertation and testing out a lot of his theories on us lucky public-schooled teenagers. He taught me Art History, Painting, Photography, and, since they didn’t have a Sculpture program, he helped me build an armature and guided me through my own sculpture projects.

SP: That’s a lot to learn from one person.

Curtis: He was a total hard-ass and scared half of the students out of class on the first day. Those of us who remained were taught to be responsible/answerable for our own research and assigned work to test our limits. “Create a painting that defies your definition of what a painting is” was my favorite project. When I came to him with the idea, he recommended I call the newspaper for coverage. That landed us a front-page story describing our project. As a young girl just starting to think about my future, he really helped to shape my identity as a person, as a citizen, and as an artist. I still see him when he comes to the University of Illinois for conferences — and he’s still teaching me things 35 years later.

SP: That’s such an incredible gift, to have a mentor.

Curtis: Yes, it is a huge gift that everyone should be lucky to receive, ideally when the ball is just getting rolling.

SP: Do you ever disagree with him?

Curtis: I would say that back in the day, he encouraged strong debate. He had a great sense of humor but was also very serious and somewhat intimidating, so we really had to put our thinking caps on. In our more recent interactions, which are short and sparse, our conversations tend to go more along the lines of “Yes! And….?” It reminds me a bit of what one of my actor friends says about doing improv: You answer with an imaginary “yes” and keep building from there. It’s very constructive but keeps the bar going higher.

SP: I’ve been doing improv for the better part of a decade, and I can say emphatically that it translates to just about any skill or profession. And you’re right! It does keep the bars and stakes going ever higher. How was it stepping out “on your own” after having such influential support in one person?

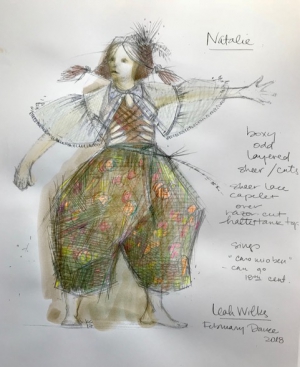

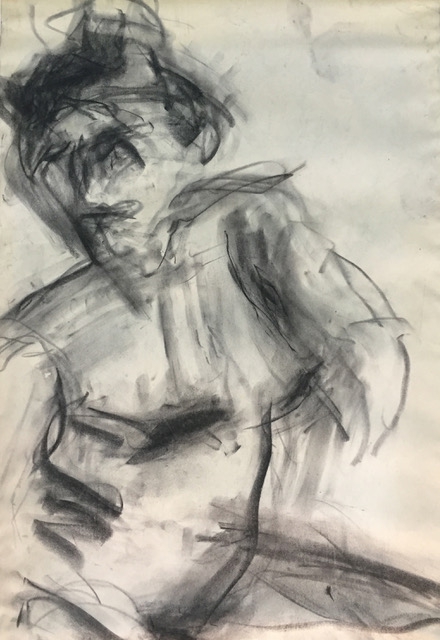

Curtis: Well, college is a whole ‘nother ball of wax and I had plenty of inspiration there too. I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do, and I moved around a lot. I started at a local community college then studied in Florence, Italy my second year, where I had a great Sculpture teacher and learned about Italian art right in front of the pieces themselves. Then I went to UC Berkeley, where I had amazing teachers in Art History, particularly one in my last year who really sat down with me and taught me how to write. The benefit in that, besides the obvious, is that writing really helps me organize my thinking in a way that I can understand my own intentions when working on a series of paintings. I did my fourth year in Goettingen, West Germany (at the time) and graduated after my fifth back at Berkeley. Those were obviously very rich years of exploration and discovering what exactly was important to me. Many years later, while working in Costume Design and construction, I went to Art school, where I worked with another phenomenal teacher who…really pushed us into new territory. We spent a lot of time drawing huge charcoal drawings from models using our [non-dominant] hand and our feet. It really changed the way I approach making art, not just in technical terms but also in visualizing aesthetic priorities and strategies.

Curtis: Well, college is a whole ‘nother ball of wax and I had plenty of inspiration there too. I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do, and I moved around a lot. I started at a local community college then studied in Florence, Italy my second year, where I had a great Sculpture teacher and learned about Italian art right in front of the pieces themselves. Then I went to UC Berkeley, where I had amazing teachers in Art History, particularly one in my last year who really sat down with me and taught me how to write. The benefit in that, besides the obvious, is that writing really helps me organize my thinking in a way that I can understand my own intentions when working on a series of paintings. I did my fourth year in Goettingen, West Germany (at the time) and graduated after my fifth back at Berkeley. Those were obviously very rich years of exploration and discovering what exactly was important to me. Many years later, while working in Costume Design and construction, I went to Art school, where I worked with another phenomenal teacher who…really pushed us into new territory. We spent a lot of time drawing huge charcoal drawings from models using our [non-dominant] hand and our feet. It really changed the way I approach making art, not just in technical terms but also in visualizing aesthetic priorities and strategies.

SP: You have really been around! What incredible experiences! I’ve looked at your paintings, and they are so unique. How did you come to this style? What’s the technique?

Curtis: There are a few things that are constant: I love oil paint and I am a pretty aggressive painter. I like to have a lot of options such as scraping back, layering on, nailing things, cutting things apart, etc., so I primarily work on wood panel, but I’ve begun to introduce found materials into the mix. The other constant is the ongoing process of creating temporary imagery until it adds up to something I like. I always work with multiple panels and force them to interact with one another. When the image of a believable landscape starts to form, I cut it apart, turn something upside-down, or move a panel to a different spot or to a different painting altogether. Then I have to deal with the new situation, which helps me go places and  find things I wouldn’t run into otherwise. It’s a process that came out of experimentation in art school and 15 years of studio time. Thematically, it works well with my current thinking regarding how we interact with our environment; how we are constantly reconfiguring our surroundings through construction, preservation, restoration and so on. Artistically, it’s both fun and frustrating because you never know where you’re going until you get there, and the imagery tends to be very messy and problematic for most of the time.

find things I wouldn’t run into otherwise. It’s a process that came out of experimentation in art school and 15 years of studio time. Thematically, it works well with my current thinking regarding how we interact with our environment; how we are constantly reconfiguring our surroundings through construction, preservation, restoration and so on. Artistically, it’s both fun and frustrating because you never know where you’re going until you get there, and the imagery tends to be very messy and problematic for most of the time.

SP: But it must be so satisfying once it comes together. In improv, I always say, “Commit completely and instantly but temporarily.” Does that sound something like what you do?

Curtis: Yes, well, thankfully, painting moves at a much slower pace than improv! And though I do commit and the paint dries, I have the benefit of un-doing, which is a large part of what I do with the scraping, cutting, and editing. I wrote an essay recently on why the eraser is my favorite drawing tool. There’s a lot you can accomplish by getting rid of stuff!

SP: Isn’t that the truth! So what do you have that we can look forward to seeing?

Curtis: In terms of upcoming stuff, I’m doing a commissioned painting for the new Lodgic space on Neil Street, and I have a show at the Evanston Art Center April 7-May 4. I also have an ongoing relationship with Prairie Rivers Network here in CU, where I donate 10% of anything I sell. usually have them come talk at my receptions. I also have an environmental commitment tab on my site.

SP: Great! Thanks so much for taking the time to talk to me.

Curtis: Would love to meet you for real sometime—and let me know [when you are] performing again!

SP: With spring coming up, I can’t escape the metaphor in Kim’s words: There’s a lot you can accomplish by getting rid of stuff. By eliminating physical and symbolic clutter in our lives, we make room for art; for creativity and experimentation. When we allow things to die and clear away, new creations can come to reach light.

________________________________________________________________________

Photos provided by Kim Curtis.