Five, six in the morning, we’d still be yapping. That was his favorite time in the world. The phrase he used was halfway to dawn … It wasn’t day and it wasn’t night … You’re half asleep. You’re half awake. Your resistance is gone—it’s like a truth serum. Your feelings just pour out.

— Marian Logan

civil rights activist, singer, Billy Strayhorn’s close friend

In honor of Strayhorn, I write this from halfway to dawn over Champaign-Urbana.

Truth serum time. I love contemporary dance, particularly when it mashes up with film/video and visual art. I’ve admired Rousséve and was all in on REALITY’S mission and approach. But when I showed up at Colwell Playhouse Friday night, I showed up for Billy.

Years ago, his music had me from the first bars of “Lush Life,” and then back again in time to take a deeper, more appreciative listen to his work with Duke Ellington. His story has continued to both haunt and inspire me. Born with a talent that overcome poverty and homophobia, Strayhorn worked beside Martin Luther King Jr. fighting for civil rights, while quietly battling his own inner demons. He left us too soon, sucumbing to esophogeal cancer at the age of 51.

Choreographer David Rousséve and his nine-performer dance/theatre company REALITY are well-known for delivering experiences that defy easy definition. I’ve heard there performances refered to as “dance portraits” and “dance plays.” Employing movement, music, and video art, REALITY dives deep into its subjects, using the unique perspectives of each art form and media to complicate, contextualize, and encourage further conversation.

They are perfectly suited for the challenging and complex task of portraying the life and music of Billy Strayhorn.

Many critics and reviewers, myself included, still hold that Strayhorn never received the recognition he deserved. But thanks to the multi-dimensional storytelling of Halfway to Dawn, that may change.

Rousséve’s choreography/theatrical direction demands both technical and emotional intelligence from his nine performers. The level of interaction extends far beyond the choreography into a theatrical performance that feels as fresh and improvised as a Strayhorn recording session.

There are far more standout moments from this performance than I could do justice to here. So I’ll limit myself to what, for me, best moved the narrative arc forward, or deepened my understanding and experience of Strayhorn’s music and life.

The music was both the soundtrack and the subject. After after opening celebration of the Strayhorn sound with the simply attired ensemble at their bouyant best, we were transported to the Cotton Club. Throughout the first act, the dancers take us through a range of emotions beginning with eager night-out joy, moving into intoxication and desire, and ending painfully with drunken disorientation, loneliness, and frustration.

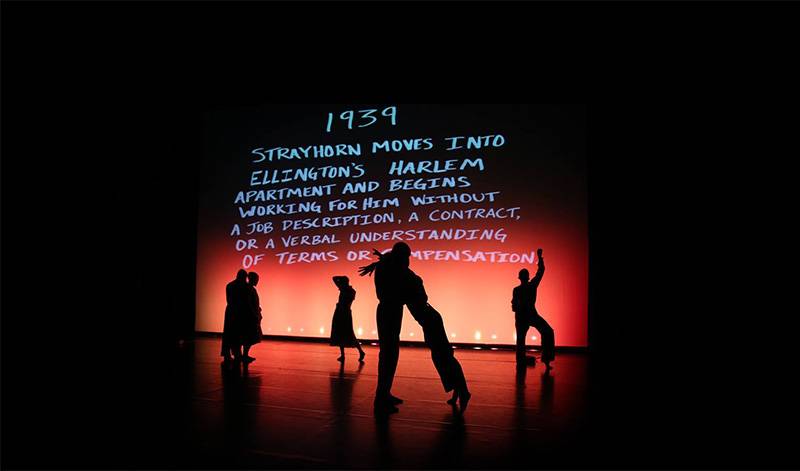

These beautifully crafted and lovingly peformed movements are set against the narrative power of Cari Ann Shim Sham artful video and screen projections. Significant milestones, from Strayhorn’s life, taken from David Hajdu’s biography Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn, appear before us in a vulnerable handwritten text that serves to underscore the many challenges and triumps of his life and career, while also speaking to his quiet humility and shyness.

Highly stylzed images of smoke and champagne conjured up that sizzlying, sparkling celebratory fantasy of Ellington’s (and Strayhorn’s) music, while also, sadly, nodding to Strayhorn’s inner demons and excesses.

Working from a seemingly ragtag pile of clothes that appeared on stage shortly after the opening, the dancers moved in and out of various looks, some reminiscent of 1940s suits and dresses, meant to add historical flavor. Yet several of the costumes, designed with efficiency and vision by Leah Piehl, went on to set the stage for a frank exploration of Strayhorn’s complicated role in musical history.

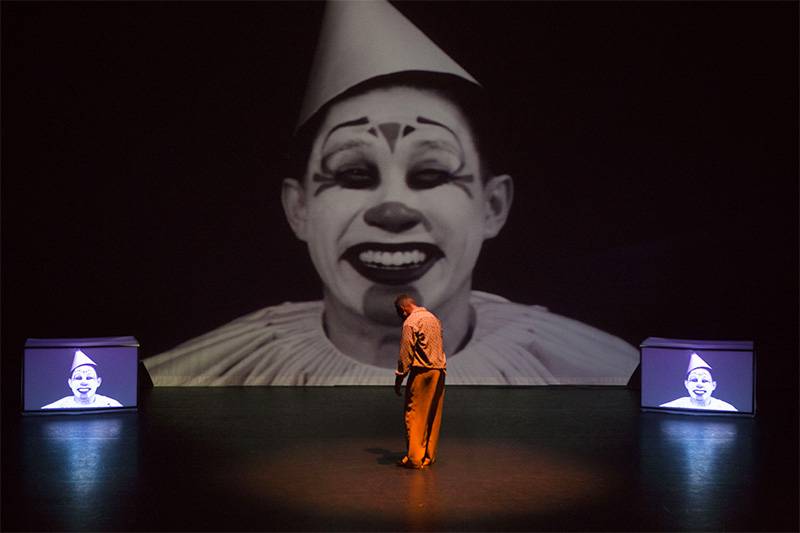

Despite living his truth as an out gay man, Strayhorn’s greatness remained largely closeted as he continued to struggle for proper credit and compensation for his significant contributions to the Ellington cannon. This tension and frustration feed into two significant tropes that appear within Halfway to Dawn: the cartoonish minstrel almost reminiscent of blackface and the sad clown.

We first encounter the exaggerated and energetic, crowd-pleasing performer against the backdrop of the Cotton Club. Donning tails and top hat, perhaps in a nod to Ellington, the figure moves from manic mirth to anger to broken down despair. The power of these moments, and the visceral discomfort they brought to some audience members, owe a debt to the acting chops of these peformers, and to the insightful and brave choices of sound designer d. Sabela grimes. When we first hear the words “party” and “fun” we hear and experience them within the context of the Cotton Club crowd. We take them quite literally. Over time, they transform into an angry battle cry. “Party” becomes an accusation, a finger pointing to Strayhorn’s frustration within Ellington’s world. Or perhaps, more globally, a nod to Strayhorn’s discomfort with a music that masks rather than gives voice to the growing power of the civil rights movement. Gradually they slow into a sound reminiscent of a broken toy, stuck in the rut of one word. The constant repetition of the word “party” becomes heartbreaking if you really allow yourself to hear it with all of its intimations and undertones. A more subtle, but equally brilliant moment of sound design occurs in the significant slowing down of “Take the A-Train” where bob begins to border on blues.

We first encounter the exaggerated and energetic, crowd-pleasing performer against the backdrop of the Cotton Club. Donning tails and top hat, perhaps in a nod to Ellington, the figure moves from manic mirth to anger to broken down despair. The power of these moments, and the visceral discomfort they brought to some audience members, owe a debt to the acting chops of these peformers, and to the insightful and brave choices of sound designer d. Sabela grimes. When we first hear the words “party” and “fun” we hear and experience them within the context of the Cotton Club crowd. We take them quite literally. Over time, they transform into an angry battle cry. “Party” becomes an accusation, a finger pointing to Strayhorn’s frustration within Ellington’s world. Or perhaps, more globally, a nod to Strayhorn’s discomfort with a music that masks rather than gives voice to the growing power of the civil rights movement. Gradually they slow into a sound reminiscent of a broken toy, stuck in the rut of one word. The constant repetition of the word “party” becomes heartbreaking if you really allow yourself to hear it with all of its intimations and undertones. A more subtle, but equally brilliant moment of sound design occurs in the significant slowing down of “Take the A-Train” where bob begins to border on blues.

Biographers have written that the sad clown trope was a deeply significant one to Strayhorne, perhaps best illustrating the dissonance between his cool cocktailing image and the long-held wounds of his interior landscape. The tension between the brilliant and eloquent composer and arranger, and the quiet child who outlived four of his siblings and escaped the wrath of an abusive father thanks to the devotion of his grandmother and mother.

So while I came for Billy, I left with a deeper appreciation of David Rousséve / REALITY’s transformative approach to dance performance’s narrative power. David Rousséve / REALITY created an experience for us to live within. At times it breathtakingly beautiful and at others it was devastatingly sad. I still find myself haunted by two particular moments. The nine dancers huddled together in front of screen, watching and reacting to civil rights footage. For several moments they stood largely in a silence and stillness that was occasionally interrupted by a comforting gesture or cry. This may sound like a small thing, but for a choreographer to stop the movment this long is significant. He is directing our eyes, our minds to the screen, and not letting us look away. The second moment is that of a dancer alone at center stage with the rest of his company seated on stools along curtain right and left, backs turned. That dancer did not enjoy having the space to himself. He did not reach out and fill it with movement. That image was perhaps the most poignant portrait of loneliness I’ve ever seen.

Thank you to David Rousséve / REALITY for the important work you do. And, to Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, for co-commissioning this piece and continuing to push the boundaries of traditional art forms, performance, and the transformative experience of empathy.

Learn more about David Rousséve / REALITY on their website

Learn more about Billy Strayhorn here

David Rousséve / REALITY: Halfway to Dawn

Krannert Center for the Performing Arts

Colwell Playhouse

500 S Goodwin Ave., Urbana

September 13th, 7:30 p.m.

Commissioned by ArtPower at UC San Diego; Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans; Kelly Strayhorn Theater, Pittsburgh; Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; NC State LIVE, Raleigh; REDCAT, Los Angeles. This presentation of Halfway to Dawn was made possible by the New England Foundation for the Arts‘ National Dance Project, with lead funding from the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Halfway to Dawn is a National Performance Network (NPN) Creation Fund Project co-commissioned by REDCAT in partnership with ArtPower at UC San Diego, Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans, the Kelly Strayhorn Theater and NPN.

Photos by Rosae Eichenbaum from the David Rousséve / REALITY website