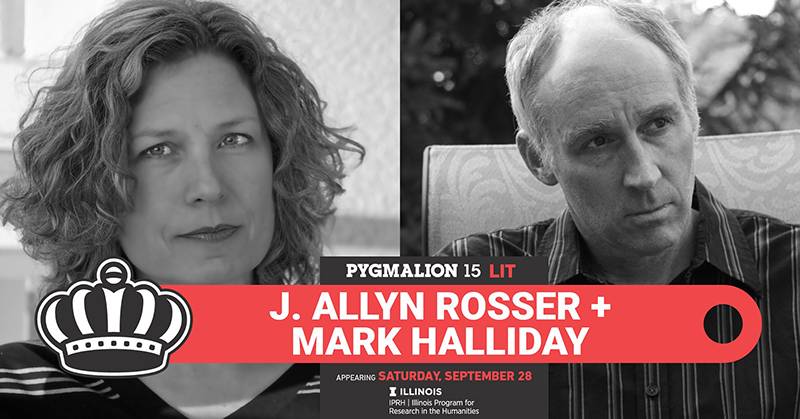

If there is a power couple of American contemporary poetry it would certainly be J. Allyn Rosser and Mark Halliday. Between them they have authored 11 collections of poetry, received the the Lavan Younger Poets Award from the Academy of American Poets and fellowships from the Lannan Foundation, the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Ohio Arts Counci (Rosser) and earned honors such as serving as the 1994 poet in residence at The Frost Place, inclusion in several annual editions of The Best American Poetry series and the Pushcart Prize anthologies, receiving a 2006 Guggenheim Fellowship, and winning the 2001 Rome Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters (Halliday).

Shifting easily through the mulitihyphenated hats of poet/teacher/editor/critic, their talents and contributions are impressive and inspiring. And best of all, they are currently on their way to Chambana to share their work at Pgymalion Festival this Saturday afternoon. For those of us in the language business, this visit is significant.

I was fortunate to have the chance to connect with them via e-mail and discuss the value of bringing poetry (as well as art and tech) to a music-based festival, balancing teaching and writing, and what it’s like being a poet in 2019 America. Their responses are insightful, witty, and guaranteed to make you want to hear them read this Saturday.

Smile Politely: We are all so excited to have you in Champaign-Urbana as part of the 2019 Pygmalion Festival. As an interdisciplinary event, Pygmalion invites poets to share the bill with musicians, tech innovators, artists and makers and other big thinkers. Did this fact impact how and what you prepared for your readings?

J. Allyn Rosser: I love reading poems at a music-centered venue, partly because music is one of my greatest passions, and in part because poetry and music are intrinsically linked – both derive from our primal need to express what the world makes us think and feel, in rhythmic patterns that convey mood and emotion. Often you can get the emotional thrust of a poem even before you understand its content, from its rhythms and sounds. And yes, no doubt I’ll select at least one poem that has to do with music, given that the Pygmalion Festival audience would naturally share my interest!

Mark Halliday: Whenever I anticipate giving a reading, I wonder about the particular audience — and usually I end up feeling I’ve guessed wrong! For instance, an audience of people mostly over thirty is very different from an audience of mostly undergraduates. Often in the past I’ve tried to be humorous, to read poems I intend as funny, but this can go wrong if I’ve guessed wrong about the audience. I think Jill and I both might decide to read a poem or two pertaining to music, since music is such a big part of the Pygmalion Festival.

Smile Politely: Speaking of tech, how do you feel digital culture has changed the landscape for poets and readers of poetry?

Rosser: I would say the digital culture has at once enriched and impoverished the reading of poetry. Enrichment by increased accessibility – you can access a LOT of poetry instantaneously and for free online, from pretty much anywhere in the world, and you can also see videos of poets performing their work. Amazing advantages! At the same time, most readers of poetry agree that reading a poem online is not as powerful or pure an aesthetic experience as reading it in the pages of a literary magazine or a book. I’m not sure the reason is wholly articulable, but there is a quality of attention and engagement with the physical page that is diluted by online reading (especially since the entire distracting world – facts, news, social media, merchandise, entertainment, all of that is pulsing right there at your fingertips). How invested are you in a moment that could turn on a dime into “Oh I need to find out x,” or “I should text so-and-so about the such-and-such”? The first poems were scratched into sand, carved into stone – we have a need for physicality in our expression. As an extreme example, there is an earnestness, a vehemence to carving something into a tree trunk or a prison wall, that is not the same as posting a tweet or flashing your fingers over a keyboard. “I was here – And I felt this!”

Halliday: Digital culture! Oh god I could talk all day about this. Nowadays not only my undergraduate students but my graduate students also are “digital natives” — they’ve never known a world without computers and the internet and social media. The cultural change is bigger than we can ever quite articulate. Throughout the Seventies and the Eighties (and for me, most of the Nineties!) writing happened on paper, reading happened on paper, and information had to be sought out on paper; all these activities required more time than they do in the digital universe. To many people my age (I’m seventy) it seems as if all these activities have become so easy that it’s harder for people to take them seriously. I worry that my students — including individuals intensely committed to literature — feel deep down that in the 21st-century, none of this work matters enough — because the production of literature and all other discourse has become so fabulously easy and ubiquitous. So I feel I am constantly trying to push back, in my tiny little ways, against the way digital culture makes all of our writings microscopic and ephemeral.

Smile Politely: You both teach and write, as well as serving in editorial roles. How do you balance the demands on your creative time and energy? Or looking at it another way, does teaching inform your writing and vice versa?

Rosser: Teaching and writing can be deeply symbiotic; talking about good poems with students is always stimulating. And the poems my students write may inspire me to try something new myself, or move in a different direction. Perhaps the most famous example of this is how Robert Lowell’s poetry was influenced by what he admired in the work of one of his student (W.D. Snodgrass).

Halliday: Teaching literature and creative writing has worked out wonderfully for me, as a writer — because I have not (since 1994 anyway) had an onerous teaching load. Teaching is full of stimulations that sooner or later nudge me toward writing a poem or essay.

Smile Politely: I’ve read quite a bit about how others have described your work. How would you describe your current work? How has it evolved?

Rosser: My poems have always reflected my fascination with any kind of human interaction and how hard it can be to communicate even the simplest things, given that one individual’s understanding of the same word can vary dramatically from another’s. I love learning new languages because of how proverbs, idioms, and even grammatical structures can make me see differently, and allow me to enter into another culture from the back door. One of the things that can get me started writing is learning about a single word or phrase in another language (or a typo in English) that turns my habitual way of thinking on its head. Right now I’m studying Hungarian, a language that doesn’t distinguish between he and she. Just one word, ő. American culture in the last decade or so has finally acted on an urgent need to create just such a pronoun, and we seem to have settled on they, which is problematic in the singular construction. I like imagining a culture in which gender is absolutely equalized (even though, like everywhere else, there has been plenty of gender discrimination in Hungary). I’m at work now on a poem about that (sadly imaginary) equalized culture.

Halliday: When I got “on track” as a poet in the early Eighties, I saw myself as a poet of “natural” speaking voice, trying to use the sound of real-life talk to express my themes and emotions. This emphasis on convincing voice has been the key element of my poetry ever since, even if I’ve attempted some exceptions and alternate experiments in a few poems in each of my seven books. I notice that in the last few years my poems seem shorter and more boldly bluntly trying to show my wisdom. This may be poetically unwise!

Smile Politely: What’s the best (or the worst) advice you’ve ever received about pursuing your craft?

Rosser: The best advice I ever received is the best advice I pass on to my students: Don’t be in such an all-fired rush to publish your poems. The advice I got was from Alexander Pope, in “Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot,” advice which in turn Pope had received from the Roman poet Horace – namely, hold onto your poem for nine years before publishing it. Nine years is rather a tall order, but time is truly one’s best friend in revision. I try to wait a year myself; I tell my students to sit on a poem for at least six months before revising, by which time its flaws will be more readily apparent to them.

The worst advice I ever received from a poet was when I was just starting to publish my poems in journals, and I was feeling overwhelmed by the obligation I felt to be familiar with all contemporary poetry. In conversation with a well-established woman poet I met at a reception, I lamented that I couldn’t keep up with all the new poetry books. She said to me, seriously, “Oh, I only read poetry by women. What do poems written by men really have to do with me, and what I’ve been through?” I was incredulous and appalled. Good poems speak to every human in every circumstance, because they reach down into what is our essential nature; they’re contemplating some very basic stuff! How can I dismiss anyone’s felt experience on this planet as irrelevant? (I draw the line at this planet. Have to draw it somewhere.)

Smile Politely: What is he best advice you give you your students or other poets and writers?

Halliday: About advice to poets — I’ve received and dished out lots, of course. One of the deepest pieces of advice I ever received was from my teacher Frank Bidart, expressed in four words: “Love what you love.” He meant that each of us should figure out what we really deeply care about and pour our energies seriously and steadfastly into that. It sounds obvious and trite when I spell it out, but “Love what you love” has helped me focus a thousand times on the poetry I want to read and the poetry I want to write.

Also: having written poems for nearly five decades, I’ve come to realize this obvious fact: ultimately you will only have written the poems you’ve written. Even in our digital life where bits of writing (including for instance this email interview!) can happen with fabulous electronic speed, and there are thousands of pathways to publication, still “at the end of the day” you will not have written “everything” that you could have written; you will only have written certain things! Therefore, what? Therefore try hard to make them good.

Smile Politely: What are the biggest challenges and/or rewards of being a poet today?

Rosser: The challenges and rewards of being a poet in 2019 are connected. It is challenging to bring your poems to the attention of a world that has so many poets writing and publishing at once – how does a drop stand out in the ocean? On the other hand, it is heartening to see how many people still care deeply about poetry – who still sit down in a quiet room (or noisy café) with a pen (or a laptop) and try to distill in words, at once our most accurate and slippery instruments of communication, what it feels like to be alive.

Smile Politely: As a country, or as a planet, we seem to be standing at such an important crossroads and, to me, this offers both challenges and opportunities to all artists, but especially to poets. Are you seeing this impact your students or feeling it in your own work?

Rosser: Every generation has felt that its own was a major historic moment, so I’m trying not to sensationalize my perspective about ours. However, with regard to the rapid extinction of species due to pesticides and human predation, and with regard to the disastrous consequences of deforestation, not to mention the threat of Weapons of Mass Destruction, the effects of fossil fuel consumption, and our ever-increasing population, it certainly feels that we are on an alarming threshold which without immediate action will prove devastating to all of our lives. I know very well that a poem ranting about any of these issues will tend to alienate readers, and this is one of the important things I discuss with students, who often feel some obligation to write politically charged poems. I have certainly written poems that respond to political issues, but I have tried to do so in surprising, oblique or subtle ways; to approach the issue from an angle that will keep the poem from haranguing the reader or sounding didactic.

Halliday: Your question about our being at a historical crossroads, in 2019, is so terrifying when we take it seriously that we all have to run away from it somehow, sometimes. The threat of climate change to the planet is monstrous, overwhelming. Moreover, the threat to American democracy, from our current national government, is also horrible. Meanwhile, ongoing problems of social injustice in America are huge; and somehow in the internet era, all sorts of victims are more informed and less passive and more actively enraged — and the pressures in our culture build and build. How should a poet respond? For me, it is a profound mistake to decide that one’s art (poetry in my case) should become a tool in the struggle for better political conditions. Serious good art always has a deep root in mystery and uncertainty. Mystery and uncertainty are not useful in any kind of political campaign. So I think a poet’s political energies and participation should go into activism (which could include political prose) — not into poems. Thank heaven for Elizabeth Warren.

And for those of you not yet familiar with Rosser and Halliday’s work, I’m included these two works to tempt you to see them in person.

Roadlight licks the night ahead, licks

the white line on night’s new hide, licks

the undulating blacktop flat, sticks its end-

less forking tongue out onward, flicks

itself at culvert, tree, passing truck, a sign

insisting heartbeats equal conscious life

(it may be) of someone’s (maybe my)

forever unborn child. I let the knife

of wind inside and sing A Whiter Shade of Pale,

no earthly reason why, and think of what

won’t be and who, and whether it be

speed, wind, song, or my mind’s roar

that drowns for once time’s slangy whine,

here comes hope to climb clear of before;

stillborn hope with desperate, Moro-reflex,

undead grip climbs right back up my neck,

raising each pointless, residual nape hair

in ancestral salute to an absence, to the air

that won’t question itself, won’t ever check

the moral rearview. I accelerate gamely,

wondering what makes me want to leave

each person, place and thing I learn to love.

What shoves me off again, racing insanely,

as if to the place that will always save

a place for me, a room that will contain

the kind of people who’d embrace the things

I’m still afraid I’m still afraid to face.“Night Drive,” Jill Allyn Rosser

I remember riding somewhere in a fast car

with my brother and his friend Jack Brooks

and we were listening to Layla & Other Love Songs

by Derek & the Dominos. The night was dark,

dark all along the highway. Jack Brooks was

a pretty funny guy, and I was delighted

by the comradely interplay between him and my brother,

but I tried not to show it for fear of inhibiting them.

I tried to be reserved and maintain a certain

dignity appropriate to my age, older by four years.

They knew the Dominos album well having played the cassette

many times, and they knew how much they liked it.

As we rode on in the dark I felt the music was,

after all, wonderful, and I said so

with as much dignity as possible. ‘That’s right,’

said my brother. ‘You’re getting smarter,’ said Jack.

We were listening to ‘Bell Bottom Blues’

at that moment. Later we were listening to

‘Key to the Highway’, and I remembered how

my brother said, ‘Yeah, yeah.’ And Jack sang

one of the lines in a way that made me laugh.

I am upset by the fact that that night is so absolutely gone.

No, ‘upset’ is too strong. Or is it.

But that night is so obscure—until now

I may not have thought of that ride once

in eight years—and this obscurity troubles me.

Death is going to defeat us all so easily.

Jack Brooks is in Florida, I believe,

and I may never see him again, which is

more or less all right with me; he and my brother

lost touch some years ago. I wonder

where we were going that night. I don’t know;

but it seemed as if we had the key to the highway.“Key to the Highway,” Mark Halliday

J. Allyn Rosser + Mark Halliday

Pygmalion Festival

Krannert Center for the Performing Arts

500 S Goodwin Ave, Urbana

This reading is free and open to all ages

September 28th, 4 to 5 p.m.

Learn more about J. Allyn Rosser and Mark Halliday

Presented in partnership with Illinois Program for Research in the Humanities (IPRH), Kirkland Fund, and the Department of English at the University of Illinois.