In these days of 24/7 bad news, it’s easy to foget what its like to be fully and joyfully surprised. But when Urbana-based multimedia artist and writer, Marc-Anthony Macon announced the arrival of his self-published book Under the Oyster Bar, a collection of short plays, I started to remember. Artists like Macon, who work in Dadaist and Surrealist traditions, know a thing or two about good surprises. And about the power of rejecting reason, which seems as appropriate a response now as it did after World War I. And because I had questions, lots of them, I reached out to Macon to learn more about his foray into this form. I hope you will enjoy his rich and revealing responses as much as I did.

Smile Politely: Local art enthusiasts know you for your Dadaist-style multimedia artwork. What inspired the movement into a collection of short plays?

Marc-Anthony Macon: It’s more of a homecoming than a movement: I studied playwriting at the University of Illinois and have a long history with fiction, stage drama, satire, performance art, and guerilla theater. Doing Dadaist collages started off as an extension of my writing, but unexpectedly and swiftly consumed it. I missed writing, but as most writers can tell you, it’s laborious and time-consuming, and making a living with it often means writing things you’re not passionate about, that no one involved in is passionate about, and the result isn’t great writing. Just money. And if I was passionate about money, I sure wouldn’t have gone into the arts. After having some success with art that I did on my own terms, I wondered what would happen if I wrote the same way that I painted: without thinking, caring, or looking back. I have a whole host of distractions I place on myself when painting to make sure I’m not overthinking it, or thinking about it at all, if I can help it. A vast, eclectic collection of music randomly shuffled, impromptu video chats, blindly-selected materials, etc. I try to be a factory worker, just zoning out and assembling things, and any meaning will be added after the fact, when I give the piece a title or, more importantly, when whomever winds up owning the piece explains what it means to them to those they share it with. I found that making art in this automatic way was not only freeing and allowed me to pump out a gluttonous proliferation of art in a short amount of time, it produced art that was nascent with meaning only the viewer could bring to finish the thought. Would that work with the playwright’s craft in the same way, some other way, or be a total disaster? Hoping for the latter, sometime in 2016, I created a routine.

Photo from the author’s Facebook page

SP: When did you start? What was your process like?

Macon: I just wrote one short play every morning, starting the moment I woke up, and before my brain could fully switch on. No matter how tired, apathetic, distracted, or uninspired I felt, I spent 20 minutes typing something, anything, as long as it could be arguably called a play, until I had about enough to fill a small book. Given that these things were written as I was waking up, it’s not too surprising that they’re mostly inspired by or in reference to a lot of what I was reading at the time: Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi plays, Lorca’s Barbarous Nights, Ed Wood’s pulp crime magazine smut, Shodo: The Quiet Art of Japanese Zen Calligraphy by Shozo Sato, Tristan Tzara’s The Approximate Man, and À Rebours by Joris-Karl Huysmans. Some days I was in a rush, and just paraphrased a conversation I overheard. Some days I was just like a worker bee vomiting up some honey flavored with whatever literary nectar I’d gobbled before bed. Some days I just wrote something fun or interesting that happened the day before. Some days I ranted via the characters. Some days I just made myself laugh. Did that for a little over a month, then filed them away and set a reminder to revisit them 2 years later and see what I’d written without much in the way of paying attention.

SP: Is this your first venture into text?

Text was most of my life from 1998-2014ish. While writing and editing other people’s projects to pay the bills, I wrote a cycle of 16 Flowers in the Attic-y pulp magical realism soap opera plays, each focusing on a different inhabitant of a small fictional town called Penwan, and those (I assure you, embarrassingly) ridiculous plays got the lion’s share of my heart and soul, so to speak. The rest of the work, while often fun and in collaboration with brilliant folks whom I admire and adore, was done primarily in service of carving out the space to write the Penwan plays. I wrote on-air and online content for Noggin, MTV Networks, Nickelodeon, Scholastic, P[r]etty Queer, Frontiers Magazine, and (spits) marketing copy eventually, which is when I started to really have enough of writing, and was was miraculously synchronous with me making bad art as a joke that more people than I expected found as funny as I did. I think having so much fun with the art helped me to remember when writing was something I had fun playing with, rather than thinking about, and I wanted to just play with writing again, rather than working at it.

SP: What was the biggest challenge in creating the book?

Macon: Not caring about writing was really tricky for me, having spent most of my adult life, and no small amount of my youth, caring about writing a whole helluva lot. Writing was my bread, my butter, my fookin’ eucharist, and I was really precious and insufferably sanctimonious about it. Letting go and just kind of urinating text into the page, like writing your name in the snow, however, turns out to be super fun and not at all a bad way to start your day, folks.

SP: What was the biggest surprise?

Macon: After that couple of years, I peeked back at it, you know, sure that it was going to be filled with radioactive wince, though fingers clenched over my face like some teeny bopper at their first horror flick. And, oh, it does get its winces, but I love those winces, and it made me laugh, too, which is equally relieving, surprising and insulting, I guess.

SP: What’s your “elevator pitch” about the book?

Macon: Unlike most books that take themselves too seriously, this one takes itself too ridiculously. Don’t buy it to read it, so much as to have something to leave in the hotel drawer to confuse the next guest/Gideon Bible-planter. I mean this. This is ridiculous business.

SP: Your book is a balm for those of us who miss having live theatre in our lives. Would you like to see them have a second life on stage someday? Why or why not?

Macon: There’s so much that I miss about the Covidless days, but I think live theatre’s what I find myself pining for the most as we wait this jerk out. As soon as we get his blustery, inebriated heap into a Lyft and on his way, I think a massive part of the party we’ll have has to be theatrical. I want to see live actors, in front of my face, engaged in the danger that only theatre can provide. Every performance is it’s own beast, and it’s an experience shared by only those in the room at that particular time. After a year of binge watching boxes, I think we all wanna be able to practically smell our performers to feel like it’s really real again. I would, surely, love to see someone try to make an evening of performing these short plays, and I would wish them the best of luck, and maybe recommend a variety of professionals that might offer them moral, legal, or psychological reasons that they should reconsider.

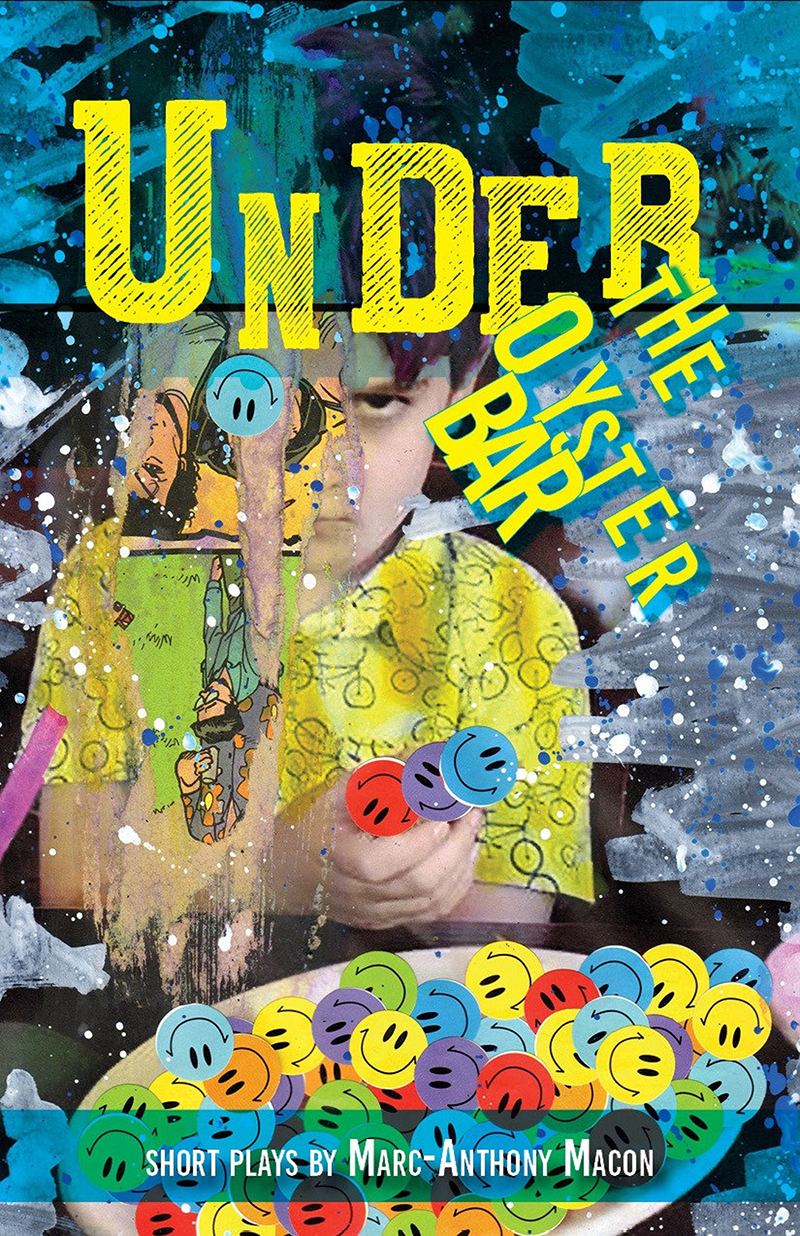

Image from Marc-Anthony Macon’s Etsy site

SP: Your work is informed by a number of traditions including Dada, Surrealism, and Absurdism. What about them inspires you? How do you define them/what do they mean to you?

Macon: Mostly, they mean no one can tell me I’m doing it wrong. Just get to skip that step altogether. Weeeeeee!

SP: Absurdist art seems like a perfectly reasonable response to our current circumstances when we are continually bombarded by increasingly unthinkable actions and responses. Do you think we’ll see a rise of work in this tradition?

Macon: Oh, I think we’ve been waist deep in absurdity for the bulk of recent memory. TikTok, Memes, Twitch, YouTube, Fox News, Aldi? I can only dream of being half as absurd as any of those things.

SP: What keeps you inspired and motivated as an artist?

Macon: Regular sleep, going for walks, reading, tea, friends and loved ones, other artists in town and globally, and just dispassionately doing the work itself every day, leaving the passion for the after party.

SP: What’s the best (or worst) advice you received as an artist?

Macon: The worst advice was Mrs. Rain in the 1st grade, who said “Good writers don’t write about living poo-poo, Marc” which turned out to be demonstrably untrue, but I do thank her, at least, for, albeit inadvertently, steering me clear of ever wanting to be a “good writer.”

SP: Anything else you’d like to share with our readers?

Macon: Don’t buy it for your gran, but maybe send one to your ex’s gran in their name?

Check out Under the Oyster Bar on the author’s Etsy site (for a signed copy), or on Amazon

Follow Marc-Anthony Macon on Tik Tok, Instagram, or Etsy