Belarus’ stolen election and ensuing protests in the summer of 2020 failed to attract much attention here in the U.S., perhaps due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the nationwide demonstrations for racial justice dominating the news cycle. But the war in Ukraine has brought renewed interest to Putin’s allyship with Belarusian President Aleksander Lukashenko, who is now two years into an unprecedented sixth term, despite the European Union calling his victory a sham. His opponent in the 2020 election, the former schoolteacher Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, currently lives in exile.

The wave of activism that overtook Belarus in the months following the rigged election amassed crowds by the thousands throughout May of 2021, after which Lukashenko severely curtailed the right to assembly. According to various human rights reports, there were at least 400 instances of citizens being tortured or sexually abused at the hands of the state police during the 11 months of rallies, not to mention dozens of protestors who died under strange circumstances. At present, estimates suggest there are around 1000 Belarusian political prisoners still behind bars.

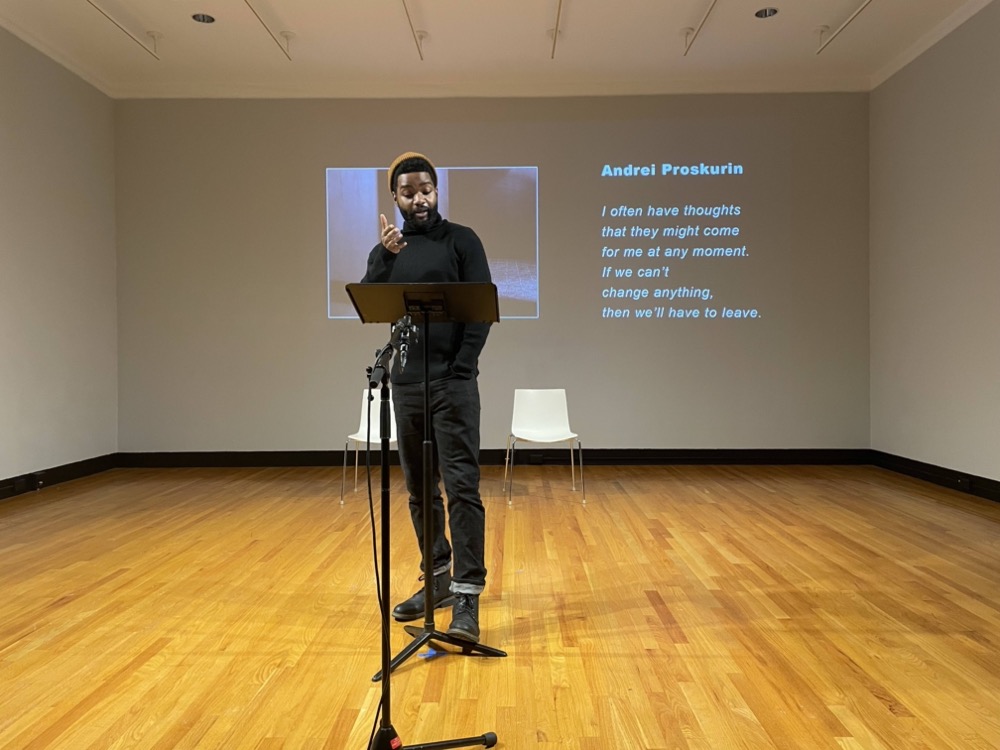

The Champaign-Urbana community heard 16 of these pro-democracy activists’ stories when the Krannert Art Museum hosted a staged reading of Andrei Kureichik’s play, Voices of the New Belarus, on April 28th. Kureichik, who was forced to flee his homeland following the protests, is currently the George A. Miller Visiting Artist at the University of Illinois.

Overcoming the staged reading format’s penchant for clumsiness, the performance was delicately directed by Kureichik and Nisi Sturgis, with seamless stage management by Katie Anthony. Voices is a documentary play, its text culled from published interviews, testimonies, and letters of Belarusians who suffered political terror during the uprising. The passages Kureichik curated offer a portrait, alternately dire and stirring, of ordinary people coalescing to free the country they love from the stranglehold of autocracy.

A blend of acting professors, student actors, and members of the university community comprised the cast. While uniformly excellent, the ensemble’s varying degrees of theatrical training enhanced the play’s commitment to its real-life characters. One felt as if a random medley of townspeople were sharing their traumatic stories with us, some with polish and command, others opting for a more homespun and unaffected presence.

Photo by Landon Sinclair.

Voices offers a collective picture of the purposeful chaos implemented by the Lukashenko administration to retain power. Many of the characters attest to being arrested for simply walking down the street, or after being forcibly removed from their cars. Once they were jailed, the demonstrators were subjected to physical violence and egregious humiliation.

Marina Karabanova, an IT worker, describes seeing prison cells filled with citizens who were stripped naked, “the walls and floor covered in blood.” After being placed in a cell designed to hold four people, the guards eventually crammed the small room with 50 women, leading to Karabanova and the others yelling that they couldn’t breathe. The next day, she was inexplicably released along with her husband.

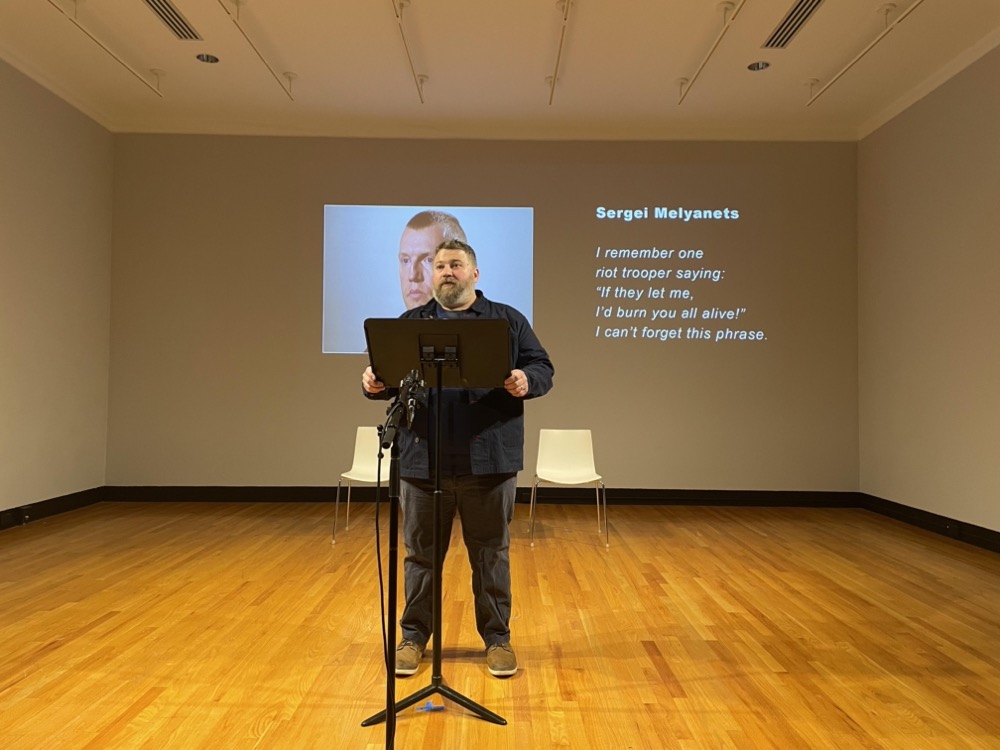

Photo by Landon Sinclair.

While being repeatedly beaten and tased by the police, Sergei Melyanets underwent an out-of-body experience: “Everything was happening to me, but, at the same time, I was watching it happen from a distance.” When he began to pass out, a doctor instructed the officers to take him to the hospital. Collapsed on the floor, Melyanets listened as they debated whether to comply. “What will you do if he dies here on the spot?” the doctor asked. Finally, the officers relented, and his condition stabilized.

These survivors of state violence offer differing opinions regarding forgiveness. Melyanets cites his Christian faith as to why he absolves his perpetrators. Polina Lagutina says she will “never in my life” forgive the police who clubbed her elderly mother. Stepan Latypov, an arborist, was sentenced to eight years in prison on dubious charges. He told the judge he will try to view him as “a person, who, perhaps, is trapped in a difficult situation,” adding that doing so “will help me not to hate you so much.” A musician named Maria Kalesnikava fears that the untold acts of violence will make peace difficult to achieve once Lukashenko loses power: “In the end, the regime will fall, and we will all have to live together.”

The fragments Kureichik selected allow his fellow citizens to be seen as more than simply vessels for the pain they have endured. For instance, Voices includes unexpected moments of gallows humor, like when Vitaly Marokko is shot in the arm by the police while protesting and politely declines a stranger’s offer to drive him to the hospital: “I couldn’t bear to ruin the interior of her car.”

Later, a local politician, Nikolai Statkevich, realizes that the state quietly altered the law so that anyone who has spoken out against the government in the past 15 years can now be charged with “organizing mass riots” — a novel way to arrest dissidents. “We should soon expect delegations coming from Venezuela, Iran,” Statkevich quips. “Belarus is finally a world leader in something!”

As their movement progressed for almost a year, the Belarusians seemed pleasantly surprised that so many people banded together to take on the man known as “Europe’s last dictator.” As Andrei Proskurin says, “Everyone knows you can leave anytime you want, but no wants to leave.”

Photo by Landon Sinclair.

With Lukashenko resorting to unconstitutional means to squash the uprising, and with so many citizens still imprisoned, Voices depicts how fascism submerges an entire nation into a kind of purgatory, insisting that normal life resume despite the overwhelming abnormality of reality itself. In a letter to his family, Alexei Berezinsky, who is serving a three-year sentence ostensibly for rioting, writes, “You often ask me how you can help me. The answer is simple: do everything you used to do together.”

It was difficult to watch Kureichik’s poignant work and not think of my own country’s struggles with democratic backsliding, and how easily our exercises of freedom and pleasure could dissolve overnight. If authoritarianism does make a serious charge at home, Belarus’ citizens provide a lesson in courage we would be prudent to emulate.