Let’s get it out of the way right up front: Michael Burns is the man. Not like The Man, the dude with his foot on your neck, keeping you down. No, we’re talking lower-case “m” here, the go-to guy, the calm in the storm, the fellow who holds things together when times get tough.

Let’s get it out of the way right up front: Michael Burns is the man. Not like The Man, the dude with his foot on your neck, keeping you down. No, we’re talking lower-case “m” here, the go-to guy, the calm in the storm, the fellow who holds things together when times get tough.

Burns’ leadership skills are apparent to his fellow volunteers at The Bike Project.

“Michael is one of the main reasons I show up on Saturdays,” noted Vince Pham. “He’s one of the nicest guys and best teachers of all-things-bike. Plus, he’s ridiculously smart. It’s not often that you get to chat with someone who will

effortlessly switch from a conversation about Aristotle and Frederick Douglass to one about the mechanics of bending a steel frame back into alignment after getting run over by a car.”

“The co-op can get pretty crowded with university students for the busy weeks in the spring and fall,” added Tony Cherolis. “Even in the chaos, Michael keeps his focus and relaxed attitude. In the middle of this distracting mess he can pick out a member in need of help and work with them intently.”

How did he acquire that preternatural calm? I sat down with Michael at The Morning Cup & More after his Saturday afternoon shift at the co-op to try to find out.

A doctoral student in English who moved to Champaign-Urbana with his wife and two young sons in the fall of 2007, Burns has packed more bike repair experience into his thirty-odd years than most folks could manage in several lifetimes. It all started when he was eight or nine years old in Fort Smith, Arkansas. “The neighborhood I grew up in — my parents bought their first house, the only house we lived in growing up — had a bunch of kids, and when we moved there, there was already a bike community set up,” Burns recalled. “We came to find out there was a communal bike pile, this huge mountain of bike parts. And if you contributed to the pile, you could take out. So, if you found whatever parts, then you could take them out and build bikes. So we built all kinds of crazy stuff, like upside-down frames, double bikes, and weird stuff.”

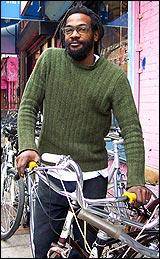

From that early start until now, Burns has repaired bikes at every stop. “Every place I’ve lived, I’ve worked in bike shops,” he said. That includes stints at Via Bicycle (a vintage shop) and Bike Line in Philadelphia (where he graduated from Temple), five summer sessions at shops on Martha’s Vineyard, and then eight years in New York City, where he worked in several capacities at NYCBikes (he’s pictured outside that shop at left).

From that early start until now, Burns has repaired bikes at every stop. “Every place I’ve lived, I’ve worked in bike shops,” he said. That includes stints at Via Bicycle (a vintage shop) and Bike Line in Philadelphia (where he graduated from Temple), five summer sessions at shops on Martha’s Vineyard, and then eight years in New York City, where he worked in several capacities at NYCBikes (he’s pictured outside that shop at left).

During Burns’ time in New York, he revived an interest in racing by his association with the Major Taylor Cycling Club, named after the legendary African-American cyclist. He also played bass for Shaka Zulu Overdrive, a black prog rock group nicknamed Brush (short for Black Rush).

The vibrant ethnic environment of New York lent itself to some interesting observations, such as, “Among Caribbean cultures, particularly, [fixed-gear bikes] are very popular. Rastas know their fixed.”

Burns also worked as a bike messenger for six or eight months while he lived in Brooklyn. “That was a lot different than commuting, because your speed is optimal. You’re trying to get something done,” he explained. “It was the type of thing where once you dull your senses to the element of danger, then you have to make a choice: are you going to stay desensitized or are you just going to go ahead and continue with this thing?”

It was a run-in with a car that finally helped him make his decision. “I had one sort of shocking accident where I kind of got nudged by a car at a stoplight and couldn’t get out in time and fell over,” Burns recalled. “When I got hit by the car, I said, ‘Wait a minute, you have a degree. You know, you can do other things.’ So, that’s when I went back to teach.” Burns had participated in Teach for America and had taught adult education before; he got his master’s degree in New York, and then came to C-U to pursue his Ph.D.

“When I came here, I was living in Champaign and I put in a couple applications [at bike shops], but pretty half-heartedly,” he said. “I really wanted to focus on my studies.”

But after meeting co-op volunteer Jeff Bertolet, Burns got involved in The Bike Project, which fills a certain void in his life. “I’m doing this academic thing, and I come from a working-class background — my father was a construction worker,” he said. “I had to work summers toting bricks, so I’m used to having sore backs and having my knuckles busted, having blisters on my hands. I’ve been doing this academic thing for so long, I feel like I need something tangible, I need to get some dirt under my nails. And the co-op gives me that outlet.”

But after meeting co-op volunteer Jeff Bertolet, Burns got involved in The Bike Project, which fills a certain void in his life. “I’m doing this academic thing, and I come from a working-class background — my father was a construction worker,” he said. “I had to work summers toting bricks, so I’m used to having sore backs and having my knuckles busted, having blisters on my hands. I’ve been doing this academic thing for so long, I feel like I need something tangible, I need to get some dirt under my nails. And the co-op gives me that outlet.”

Burns’ bike fleet is shallow in numbers but deeply unique. He has an ’89 Fisher from before the Trek buyout, a Cuevas fixie — hand-picked from the late builder’s shop on the Lower East Side — and a NYCBikes prototype: “that’s my go-fast bike.”

That “academic thing” means, unfortunately for the rest of us, that Burns’ life in C-U has an expiration date. “My deal is six years, but my wife gave me four,” he said. “So I think it’ll be closer to four than six.” That’s obviously a bummer, but we’ve got at least two more years to benefit from Michael’s presence, which is certainly a blessing.

Here are a couple bonus quotes about Burns from other Bike Project volunteers:

“He is one of the nicest, most patient people I have known. He is always willing to help people in the Bike Project. I have never heard a negative word come out of his mouth.” –Todd Spinner

“I volunteer at the co-op on Saturdays. He knows a lot about all kinds of bicycles and will figure out anything. Whether it’s helping with something really basic but I don’t know it yet … or figuring out something weird on the insides of a bike from Holland … Mike’s the guy to ask.” –Sue Jones

——

If you enjoyed this article, Smile Politely also recommends:

+ Tales of winter commutes

+ Get to Know ‘Em: Greg Busch and Lisa Hall keep things interesting

+ Get to Know ‘Em: Sue Jones

+ Meet a real, live bicycle rider