Read Part One and Part Two of the Safe Haven series.

Homelessness: Not in Our Town.

This seems to be the approach some people take to the homeless living on the fringes of our community; they’d prefer to oust homeless people from society and deny the existence of the current housing crisis. But the problem of homelessness exists — in Champaign-Urbana and in every city around the globe. The challenge lies in how we, as a community, respond to the problem. Some communities on the West Coast are responding to the problem creatively, and Safe Haven in Champaign would like to follow suit.

News media have made it clear that living in tents is not allowed under City of Champaign zoning ordinances. Safe Haven is currently located in the backyard of Champaign’s Catholic Worker House. The Catholic Worker House is zoned to provide shelter, but only within a “permanent structure.”

The city has said, however, that they are interested in finding other options for Safe Haven residents. Jesse Masengale, 22, Safe Haven resident, and Abby Harmon, 27, Safe Haven advocate, said that the city is neither working with Safe Haven, nor working against them. At this point, the city is simply not engaging them. Safe Haven does hope, though, to work with the city to find a viable solution.

John Sullivan, Executive Director of Center for Women in Transition, believes the city should provide affordable housing so that a tent community is not needed. But with the current housing crisis, he sees a need for Safe Haven.

“Tent communities are acceptable and accessible because all you need is a tent,” Sullivan said. “But what happens when it’s cold outside?”

Sullivan has proposed that the city allow Safe Haven to utilize an empty warehouse, particularly during the cold winter months. Safe Haven residents could set up their tents inside the warehouse. The warehouse would not need to be heated, but it would provide a roof and some extra protection from harsh winter weather. Further, the building could offer a toilet and running water.

Sullivan also pointed out that there are hundreds of empty housing units in C-U that are currently not occupied. Would it be possible to reallocate some of that space to house the homeless?

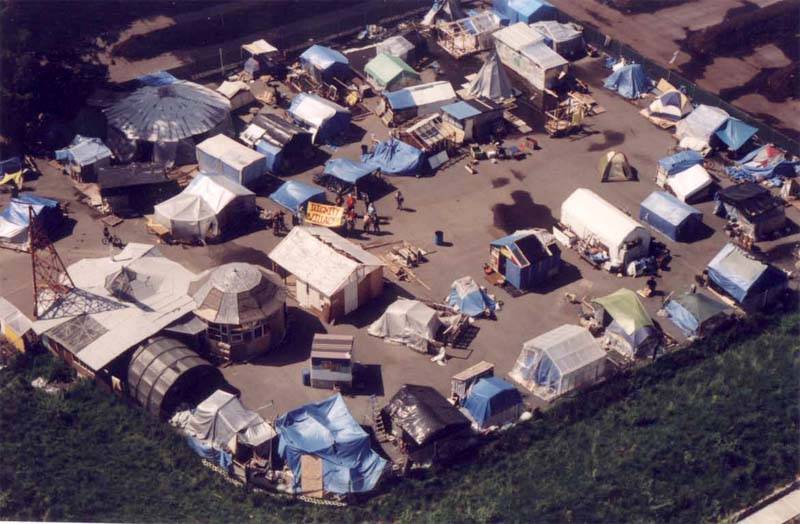

Of all the alternatives, Safe Haven’s ideal is to acquire an acre or several acres of land and to become a semi-permanent village, modeled after Dignity Village in Portland, Ore (pictured above). They desire to be a self-sustaining community — growing their own food, having their own sanitation/sewer system, and living outside the costly shelters.

Harmon pointed out that all laws are created by humans, and these laws can and do change all the time. Law is dynamic, not static. Portland provides a great example of a city who has worked with the homeless to revise zoning ordinances and establish a successful tent city.

Dignity Village (initially inspired by a Los Angeles homeless camp called Justiceville) started as a group of eight people living in donated tents. At first, the tent community was considered illegal and had an antagonistic relationship with the City of Portland. Over time, political support grew, and the Portland City Commission agreed in September 2001 that campers could stay on part of the city-owned leaf-composting site for 60 days, located near the Portland International Airport and a county jail. Years later, they’re still there.

This experimental community is now home to 60 people, ranging in age from late teens to late 60s. According to an article on Dignity Village called “Guerrilla City,” the village has worked with community activist and architect Mark Lakeman to construct small houses, made of discarded lumber or plywood sheets and other salvaged materials. A town hall and community center provide space for government meetings, a communal kitchen, and propane-heated showers. Four portable toilets are also part of the village’s landscape.

This experimental community is now home to 60 people, ranging in age from late teens to late 60s. According to an article on Dignity Village called “Guerrilla City,” the village has worked with community activist and architect Mark Lakeman to construct small houses, made of discarded lumber or plywood sheets and other salvaged materials. A town hall and community center provide space for government meetings, a communal kitchen, and propane-heated showers. Four portable toilets are also part of the village’s landscape.

Dignity Village is self-governed, with elected officials and weekly council meetings. In the article “Olympia’s tent city looks to Portland camp as model,” the Portland Police Bureau confirmed that Dignity Village’s self-policing system has proven effective. Police only had to visit the camp three times during the last year. The village is also economically self-reliant and environmentally sustainable. Former Portland Mayor Tom Potter declared this homegrown version of transitional housing a success.

In 2004, the City of Portland granted the village campground status and is now considering a 10-year lease for the former composting site. For homeless people involved in the camp, Dignity Village has allowed them to take more control over their own lives and has given them a sense of belonging and support. The village does more than give residents a place to sleep for the night; it gives them a home and a community.

Champaign’s Safe Haven would like to follow Dignity Village’s example to develop a self-sustainable, semi-permanent village, and they seek your support. As their brochure states, “We ask for your trust and support over the coming months as we seek to become a more established and accepted part of the [larger Champaign-Urbana] community.”

Those interested in supporting Safe Haven can help by donating camping supplies, such as tents, sleeping bags, pillows, blankets, tarps, bug spray, stakes, tiki torches, or water. Safe Haven could also use paper, envelopes, stamps, and printing/copying donations as they prepare to send mailings to various community groups.

“Tent cities are more than just models of alternative housing. They represent a basic foundation of human dignity. It’s not just about a roof over our heads; it’s about HOME. It’s not just about a place to stay; it’s about COMMUNITY” (from Tent Cities Toolkit website).