I came to Urbana on the Wabash Cannonball.

I came to Urbana on the Wabash Cannonball.

Actually we detrained in Tolono, a whistle stop on the Cannonball’s Detroit to St. Louis run. We had departed from Detroit’s enormous, ornate Michigan Central Station, pulled by a rumbling navy blue and yellow Wabash Railroad locomotive. I don’t remember much else about the trip except for the dining car service–crisp white linen, railroad china, silver service-ware, elegant upright negro waiters displaying that weird combination of professionalism and servility–and my mother’s dismay at our arrival at the shabby little station in desolate Tolono.

All that’s mostly gone now, some of it thankfully so. Our first Urbana house, a cheap white box on slab in the U of I Bliss Drive housing development, is gone too, the street now closed to traffic by huge concrete flower pots. They tore the houses down several years ago, but I can still find the backyard bushes and trees that were first, second, third and homeplate. The neighborhood is now just a big empty space with a street weirdly running through the middle of it. It reminds me of today’s Detroit.

The Wabash Cannonball I rode was not one of song. That was, as Utah Phillips once explained, “a mythological train made up by some bum somewhere” in the 1880s, “the train that any old hobo would ride on the way to his reward, wherever that might be. There never was a train called the Wabash Cannonball that went ‘from the great Atlantic Ocean to the wide Pacific shore.” Well, except the Cannonball that the Wabash RR decided was a good marketing gimmick for a train that ran from St. Louis to Detroit at least.

Detroit is currently trying to decide whether to tear down the long-abandoned Michigan Central Station I departed from in those glorious ’50s. It’s in better shape, but not by much, than the vast Packard plant that is improbably still there more than a half a century after the last Packard rolled off the line, or the Highland Park factory where Henry Ford first turned out the Model T’s that created the modern industrial world. Nearby you can see large flocks of pheasants in the urban wasteland that is returning to prairie

It’s sobering to see the material world you’ve known in absolute ruins. (Insert random verse from Ecclesiastes here). But it’s easy to forget it, and those still in it, and to march forward, as instructed, into that ever brighter future on the ever-receding horizon.

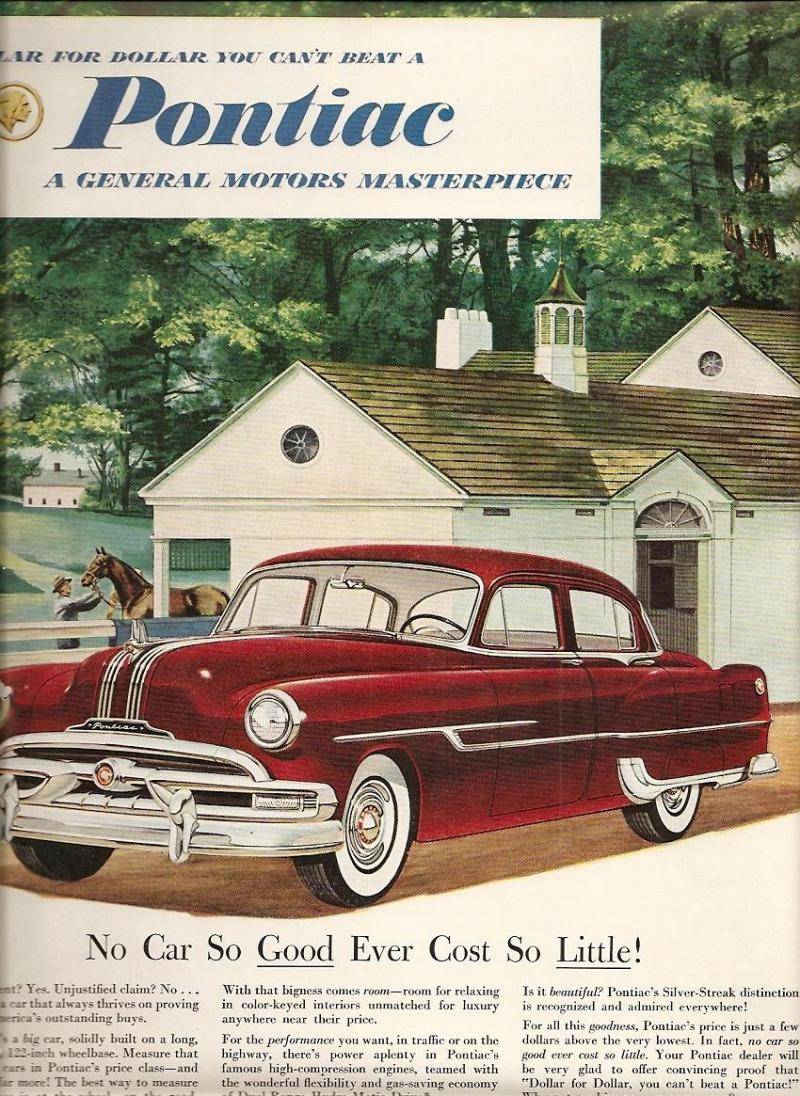

My family is from Pontiac, and we’ve pretty much always been a Pontiac family, although my dad, having reached old age and acting it, now drives a Buick 6. We always had a Pontiac in the drive, and he picked us up in Tolono in a ’53 Chieftain. But enough revisiting of my migration corridor.

My family is from Pontiac, and we’ve pretty much always been a Pontiac family, although my dad, having reached old age and acting it, now drives a Buick 6. We always had a Pontiac in the drive, and he picked us up in Tolono in a ’53 Chieftain. But enough revisiting of my migration corridor.

You do not want to be in Pontiac today. They quit assembling the car there years ago, and GM is closing the GMC plant. A tough town got tougher; even its namesake is now history. I have kin there now out of work, along with several thousand more people in the neighborhood. They once migrated to Tennessee to work at the new Saturn plant, but came back to be closer to family. No point in going back to Tennessee since GM is closing that plant, too. Maybe they should move here. Of course they’d have to sell their house in southeastern Michigan. Good luck with that.

When I hear some smug economist, being part of the “creative class,” wax on about “creative destruction,” I reach for my revolver. Economists live in towns like Urbana-Champaign on some sinecure, well-insulated from the destruction. There are no economists living in Pontiac, and there is nothing creative about working on the line, in an auto factory or at Solo Cup, or Plastipak, or Burger King. It is mind-numbing labor, but what else are you going to do, sell real estate to each other? What else do you have for sale?

What the creative (destructive?) classes here are up to is a bit of a mystery, but it’s probably supposed to be a little mystifying, a quality that can separate a creative type from the hoi polloi. Still, are we making anything that gives sustenance to the vast unwashed masses yet, besides time-killing apps or video games?

Billions of dollars are being spent on genetically modified organisms (turning life itself into private property), on nano-technology (I can’t read my cell phone already, I don’t need smaller), data-mining (hello, DOD), computer aided or assisted this or that or everything, or other silver ultra-fast techno-bullets that boosters claim to be the promise our salvation. Someone once dubbed this the “technological sublime.”

Technological dynamos may be awe-inspiring, but we still can’t develop a railroad a tenth as good as the one we had in the ’50s, jobs continue to vanish, families unravel, and the U of I still can’t figure out what to do with that land on the corner of Race and Florida, except wall it off with flower pots that look like gussied-up sewer pipe.

Why is the story of creative destruction as life improvement any more believable than the story of the Wabash Cannonball as life’s reward? The distance between them is not all that great, except that one is written by the whip hand, the other by the multitude.

Here in C-U we can look at the dismal Country Fair shopping center and wonder what the UI research park might look like in 50 years. Of course being so much more intelligent and learned, our conceit is that now we can truly see the future. Could Urbana-Champaign ever look like today’s Detroit? Of course not. Which is the same answer people in Detroit gave in 1957.