One of the big stories around here in the early 1950s was the building of a multi-million dollar petrochemical and fertilizer plant in Tuscola. It even made Time magazine. It was a booming (sometimes literally when plants blew up) business to be in back then. Nitrogen fertilizer, made cheaply with natural gas, was being dumped willy-nilly on farmland across the country. Tuscola was chosen mainly because it’s on a major natural gas pipeline.

One of the big stories around here in the early 1950s was the building of a multi-million dollar petrochemical and fertilizer plant in Tuscola. It even made Time magazine. It was a booming (sometimes literally when plants blew up) business to be in back then. Nitrogen fertilizer, made cheaply with natural gas, was being dumped willy-nilly on farmland across the country. Tuscola was chosen mainly because it’s on a major natural gas pipeline.

Inorganic fertilizers were not that commonly used before WWII. When the war ended, the factories built to produce ammonia for munitions switched to producing cheap nitrogen fertilizer. [A similar story exists around chemical weapon production and the post-war pesticide industry, but that’s for another day.]

When farmers saw the yield increases inorganic fertilizer afforded, they went nuts. By the early 1950s ammonia production had doubled from 1946, and farmers increasingly planted only one or two cash crops, significantly curtailing the crop rotation that protects soil fertility. It was possible because the new fertilizers could restore the nitrogen the crops had taken out of the soil. This trend continued for years, shooting up in the ’60s and ’70s, before beginning to level off in the mid ’80s (partly due to university research and outreach that showed farmers they were putting on excessive amounts). Total yields soared along with fertilizer tonnage, and today inorganic fertilizer is applied to nearly all U.S. corn acreage.

The U.S. was still the world’s largest exporter of nitrogen fertilizer in the 1980s, but became the world’s largest importer in the 1990s as demand for natural gas rose significantly, outstripping domestic production, driving up price, and driving domestic fertilizer producers such as the one in Tuscola out of business. We now import more than half of our nitrogen from places with lower natural gas prices, mainly Trinidad and Tobago, but also from Russia.

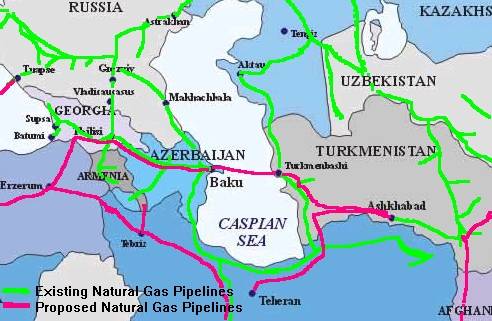

Russia? We should note that V. Putin’s doctorate from the St. Petersburg Mining Institute concerned “Mineral Natural Resources in the Strategy for Development of the Russian Economy.” Hmmm, probably more to it than that, as these headlines from October 12–14 indicate: “Gas Pipeline Drives Political Wedge Between Europe,” “Russia Gas Pipeline Heightens East Europe’s Fears,” “China Signs Deal for Gas in Trade Talk With Putin.” What’s going on here? And what does this have to do with nitrogen fertilizer, or Champaign County for that matter? Well, not a lot……yet. But let’s ramble about a bit more.

Some facts:

- Russia is the world’s biggest energy producer.

- China is the world’s biggest energy user after the United States.

- Russia supplies Europe with 41 percent of its gas, a figure that will likely jump when new pipelines under the Baltic Sea come on line in 2011 and 2014.

So what are those pipelines about? Here’s what former leaders from 23 Central European states wrote in a letter to President Obama this spring: “Russia is back as a revisionist power pursuing a 19th-century agenda with 21st-century tactics.” Or as one former Polish official said, “Yesterday tanks, today oil.” Yikes!

19th century agenda? That sounds like the Great Game, the competition between Russia and Britain over Afghanistan and Central Asia. The more things change… The peripatetic Brazilian journalist Pepe Escobar recently put it like this: “The new great game of the 21st century is always over energy and it’s taking place on an immense chessboard called Eurasia. Its squares are defined by the networks of pipelines being laid across the oil heartlands of the planet. Call it Pipelineistan. …Think of this as the real political thriller of our time.”

First let’s look at the political thrillers of 100 years ago, which ended in catastrophe. The Great Game itself ended when Russia and Britain came to terms to divvy up Afghanistan and Persia in 1907. The precipitating event was worry over the German plan to build a railway to Baghdad, and increasing German activity in what would be Iraq and Iran. [As an aside, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, which would become British Petroleum, which would buy up Amoco and now owns your local BP station, was organized in 1908, the first exploitation of the Middle Eastern oil reserves.]

The 1907 Russo-Anglo agreement was one of three agreements that made up the famed Triple Entente of France-Britain-Russia; made with an eye to constraining the rising technological, industrial and military juggernaut of Germany, where scientists like Fritz Haber were in 1909 figuring out how to make ammonia from air.

The proximate causes of the First World War are debatable, but Lenin’s notion that it was at base a clash of imperial capitalist powers over resources and markets seems about right. While the two world wars (in some ways just two acts of one war) fundamentally reshaped the world, we are still in the era of imperialist capitalist powers chasing resources and markets. Today they are the EU-US axis, Russia, and the new player on the block, China. What’s eerily the same is the contest over central Asia. And it’s primarily about the control of gas.

The proximate causes of the First World War are debatable, but Lenin’s notion that it was at base a clash of imperial capitalist powers over resources and markets seems about right. While the two world wars (in some ways just two acts of one war) fundamentally reshaped the world, we are still in the era of imperialist capitalist powers chasing resources and markets. Today they are the EU-US axis, Russia, and the new player on the block, China. What’s eerily the same is the contest over central Asia. And it’s primarily about the control of gas.

Following the gas world is insanely complicated, and trying to forecast it’s future is often a crapshoot — there are too many variables. But some long-run trends can be discerned — the issue is timing. Today, the price of gas worldwide has collapsed, largely from the recession, but also from new U.S. technology that has unlocked a huge reserve of previously inaccessible gas trapped in shale (and which the west hopes will be applicable in Europe and elsewhere), and from the increasing infrastructure that allows gas to be liquefied in places like the Middle East, shipped, then put into pipelines, which globalizes supply lines. Russia is delivering gas to Europe at long-term contract prices that are now well over twice the world spot price of gas. The pressure to lower prices is intense, but one wonders how long the glut will last. Because everybody loves gas. Look at China

Some quotes from the October 15 A.P. article on the Sino-Russian gas deal are illustrative:

Some quotes from the October 15 A.P. article on the Sino-Russian gas deal are illustrative:

“Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin on Wednesday wrapped up a three-day visit to the Chinese capital, during which Russia … set the framework for a separate, multibillion-dollar agreement to build two natural gas pipelines to China from gas fields in Russia’s Far East. Together, those pipelines would be capable of supplying China … a whopping 85 percent of the gas China currently consumes.”

“The agreement … reflects a political desire by both to steer a course independent of Western powers and especially the United States.”

“China already produces [95% of the gas it uses], with most of the rest coming from Australia as liquefied natural gas. So there are no gas shortages. But Beijing is gradually replacing coal and other energy sources with cleaner-burning gas…”

“In addition, China is building a 4,000-mile pipeline to bring 30 billion cubic meters of gas annually from Turkmenistan in Central Asia… ‘China is playing the long game,’ [A Moscow bank analyst] said.”

“In addition, China is building a 4,000-mile pipeline to bring 30 billion cubic meters of gas annually from Turkmenistan in Central Asia… ‘China is playing the long game,’ [A Moscow bank analyst] said.”

Take note of what China’s rapid industrialization has done to worldwide prices of many natural resources, such as copper.

And consider what it might to do to gas prices, and thus the price of fertilizer that’s one of the foundations of the industrial agriculture to which our local economy is so far inextricably bound. And consider what this all might mean about why soldiers from here have been in Pipelineistan. In the next chapter, we’ll try to bring this all back home.