On Thanksgiving, my aunt started a rousing discussion of the inherited physical traits that have manifested themselves in different members of the family, across generational lines. My cousin, with the typical long-toed feet, is apparently a carbon copy of my dad in his youth, some people have distinctly large noses, and almost everyone is blonde and fair-skinned, if not blue-eyed.

On Thanksgiving, my aunt started a rousing discussion of the inherited physical traits that have manifested themselves in different members of the family, across generational lines. My cousin, with the typical long-toed feet, is apparently a carbon copy of my dad in his youth, some people have distinctly large noses, and almost everyone is blonde and fair-skinned, if not blue-eyed.

Except for me. I have none of these genetic traits. My hair is dark brown (“black”), my almond-shaped eyes are mono-lidded, and I have stocky legs and big calves. In short, I am a full-blown Korean, adopted into a family of Scotch-Irish and German descendants.

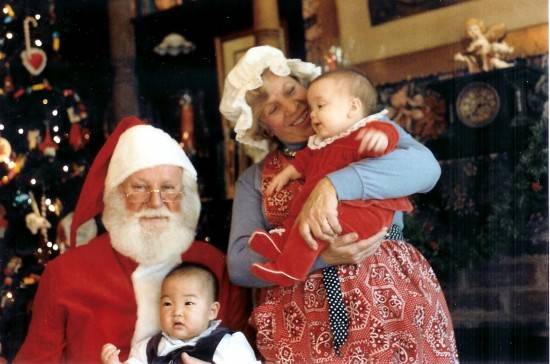

I have always been aware of the fact that I was adopted, and for as long as I can remember, it has been a great source of pride and interest. I enjoy looking exotic but being fully assimilated into American culture. I have heard the details of my arrival on July 3rd, 1986 hundreds of times — from the difficulty my parents had getting to New York City the day before the Bicentennial celebration to my tear-less entrance into the airport. These people are my mom and my dad, no qualifying adjective needed, and I am thankful for the combination of circumstances that brought our lives together.

Until recently, my Korean heritage didn’t factor very heavily in my life. I know very little Korean (I can count to ten and pronounce the trans-literated English names of common dishes.), and I have never been back to my birth country. Going to Europe always seemed more appealing than going back to a country where I would “look the part” but depend on others for even the most basic communication. With loving and gregarious adoptive relatives, there has never been a void in my life for some kind of family connection, so searching for my birth parents was never a consideration.

Last year, the blog of an adopted Korean reunited with his birth family sparked my interest in searching for my biological parents. Realizing that I might later regret not starting a search, I contacted my adoption agency to begin the process right away.

Adoption involves three parties: not only the birth parents and the adoptee, but also the adoptive parents, who are often left out of the picture. From what I can tell, most adoptees are not as lucky as I am to have strong support in their searches. Adoptive parents can be reluctant to discuss the adoption process and sometimes interpret their child’s search as a personal rejection. Fortunately, that was not my case. When I told my dad that I was initiating a search for my birth parents, he immediately scanned and e-mailed all of the relevant documents to me. My mom said that it was a great idea.

After I sent in the application for a search to my U.S. agency, a request to pull my file from storage was forwarded to the Korean agency that facilitated my adoption. From this file, I was given all of the “non-identifying” information about my biological parents. Due to Korean privacy laws, birth parents must consent before confidential and identifying information is released to the other parts of the adoption triad.

Part of the file was devoted to descriptions of my infant self, case # K86-1458. Born a month premature, I weighed less than five pounds and was noticeably jaundiced. Under the care of a “loving” foster family, I was quickly deemed “early adoptable” and was apparently cute and happy with “good sucking power.” My Korean first name Eun Me (“Beautiful Silver”) was a government-given name, but was later changed when I arrived in the US.

The brief and matter-of-fact paragraph describing my biological family reads like a plot proposal for a depressing Lifetime Original Movie. My birth mother was 5’4″ and was “mild.” My birth father was a whopping 5’7″, a college graduate, and was “introspective.” (Interestingly, I am only 5’3″ and consider myself neither mild nor introspective.) They had been together for five years and “had plans to marry.” After he was called away for mandatory military service, my birth mom discovered that she was pregnant. However, my biological father became ill during his period of mandatory conscription, and their marriage plans fell through. Unable to raise a child in a society that stigmatized unwed mothers, my birth mother turned to Holt Children’s Services and gave me up for adoption.

Along with this information came a note from Ms. Lee, the Korean social worker assigned to my search. As luck would have it, she has enough information to attempt to confidentially contact my birth mother. Ms. Lee requested that I send a note to introduce myself as well as a few photographs. Out of the 2000+ photos on my computer, I had a strangely hard time finding any “normal” pictures of myself in which I am not making an ugly face or doing something ridiculous. For obvious reasons, the letter was difficult and awkward to compose. I wrote that I am happy and healthy, that I am working towards an advanced degree, that I just ran my first marathon, that I’m getting my first dog, etc. All of these things seemed like things I would want to hear, but who knows how they could be received.

Now, I have to wait for a response. Apparently, one common adoptee experience in birth family searches is learning that we are not in control of the situation. (Since I am unabashedly a control freak, this is proving quite difficult.) My birth mother has every right to refuse communication with me. If she has remarried and established herself, she may have concealed her pregnancy to her friends and family, which would obviously put her in a precarious position. This baby-turned-adult whom she last saw 23 years ago might be a painful reminder of a past that she blocked out of her memory. In the end, the adoption agency might not be able to contact her at all.

I have nothing to lose from launching this search, though I do worry about what it will feel like if she refuses to communicate with me. From reading a few memoirs and other accounts of Korean adoptees, I have learned that I am oddly in some kind of emotional minority, wholly positive about my adoption and harboring no resentment towards either set of parents. Ultimately, I hope that this search proves fruitful because if, for no other than this selfish reason, I would really like to see where all my physical traits come from.