Lee and I were watching 60 Minutes when Lesley Stahl reported about a man convicted of rape because his accuser had wrongly remembered his face. The accuser was sure this was the man who had attacked her. She had deliberately studied his face during the attack. He was the one.

Lee and I were watching 60 Minutes when Lesley Stahl reported about a man convicted of rape because his accuser had wrongly remembered his face. The accuser was sure this was the man who had attacked her. She had deliberately studied his face during the attack. He was the one.

A decade later, the truth came out. Her memory had been wrong. The woman was devastated. The man got out of prison, forgave her, and they are now friends, traveling together and telling their amazing story.

But the second half of the program, in a sense, was the important part. Stahl met with psychologists who showed her pictures and tested her memory and the memories of those of us watching on TV as well. Stahl flunked. So did I.

Things that happened decades ago may become blurrier, or they may be enhanced by imagination and repetitive recounting. If you’re 25 now, first grade may seem a little hazy to you. And 20 years down the road, when you’re 45, you probably won’t recall the clothes you are wearing today. Even if you are posting Facebook status lines and blogging constantly, you can’t keep track of everything.

And the likelihood is great that you are embellishing, modifying, revising, editing the past into a narrative marked by a degree of inventiveness, not unlike turning the time machine wheel on Lost and learning the past isn’t all it is cracked up to be. The past is just an illusion.

But, I want to remember all these minute details of the past. I want to dredge them up like an old Beta video tape. I want to peer into my grade school classroom and watch it all again. I want to see the most banal moment of life when I was 18. I want to know what I ate for breakfast in 1984.

It seems I only can conjure vague glimpses, sometimes fueled by photographs. As an experiment, I decided to reconstruct details about the first trip I took to South America. It was in the summer of 1972, so that was 37 years ago. I’m going to narrow it down, to try to remember what I saw, wore, and experienced on the very day I turned 23.

That would have been on July 23, the cusp of Leo and Cancer. I was staying at the home of an expatriate couple I had met traveling. That night, we had gone to a movie, The Sound of Music, in the little town of Fusagasugá, Colombia. The church bells chimed at midnight, when the movie ended.

At least, I think that much is true. But why would the bells have chimed at midnight? Maybe we had seen the Orson Welles movie, Chimes at Midnight, and listened to Julie Andrews later.

I need to set things up a bit and work my way toward that day. Kevin Casey and I hitchhiked from Denver, where we both had been working in menial jobs. We had big aluminum frame backpacks, enough molasses protein bread (which Lee had baked) to last us a couple of weeks, and a hand-lettered sign that read “Lima” as we stood on the interstate ramp outside Denver, thumbs out.

I have told this part of the story before. It has become one of those stories that people of a certain age find themselves telling over and over while their loved ones nod politely and friends roll their eyes. So, sue me.

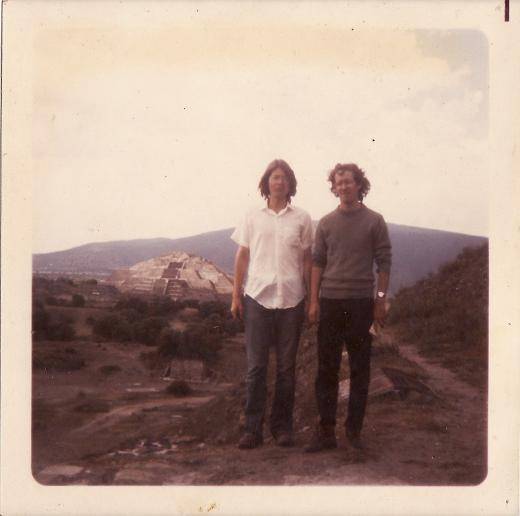

I dug through my boxes and found the one picture I have from the trip. My Instamatic camera was stolen in Panama, but not before I had saved one roll of film. I don’t know what happened to the other pictures. Only the one is left.

In the picture, Kevin and I are standing in front of Teotihuacán, the Pyramid of the Sun, outside Mexico City. I had remembered incorrectly the picture as being in black and white, but it is in faded color. I am surprised to see I am wearing a watch. I thought I had renounced watches then.

Neither of us had been out of the country before and here we were, adrift in a foreign land before the world had cell phones, ATM machines, computers, iPods, or airplanes. OK, airplanes existed, but for all practical purposes we were away from anything we had ever known and without any easy recourse to return. We might as well have been on Mars.

I remember getting sick in Tapachula from cool but deadly street vendor fruit drinks. We slept by the side of the road in Guatemala, and in the morning a woman brought us coffee. We took a ferry from La Union, El Salvador, to a butterfly-infested landscape in Nicaragua. We wandered, lost, through banana fields in Costa Rica. We encountered no tourists anywhere in the months we were gone, except for a couple from Spain.

When we got to Panama, we learned that the Pan-American Highway did not go through the jungle into Colombia at all. It still doesn’t. The road ends there.

Then, it’s a blank. I remember almost nothing about coming into Panama City, except that it was the most Americanized and least attractive place we had seen on the trip. We ate at a McDonalds. We bought very cheap airplane tickets from Avianca and then waited for the flight in a hovel with open-top cubicles rather than rooms, where someone blared a record player all night long. I can still hear the song. It was horrible. This part of the trip I have not romanticized.

I remember flying into Bogotá, seeing from above the antique U.S. automobiles people drove while ignoring red lights, and rows of greenhouses filled with flowers.

Everything was so inexpensive, we felt wealthy. We explored the town. I remember a few things specifically. We caught a screening of Last Tango in Paris, and there were multiple language subtitles. We attended the International Flower Show at the edge of a park. And the soups of Colombia were rich and delicious, with tiny corn cobs and vegetables and thick, savory broths.

I don’t know how many days we spent in Bogotá or the order anything took place. There was no talk of the FARC or guerrilla terrorists in Bogotá at that time. Instead, there had been publicity: a photo spread in Life Magazine, as I recall, about the homeless children in the capital of Colombia. Children living on their own on the street was less of a world phenomenon back then.

I don’t remember at all how Kevin and I met the couple from Fusagasugá. I don’t remember their names. I vaguely remember what they looked like. He had been in prison in Morocco. She had long hair and made candy out of condensed milk and hashish. They owned a Peruvian sloth as a pet that they kept outside in a large caged room. We stayed with them a week before hitching out across the equator and into the Southern hemisphere, to find a toilet to flush (not necessarily an easy task) to see if the water swirled down in a counter-clockwise direction.

And that is about all I can remember related to that day. It’s broad; the details of my birthday are nonexistent. I can see from the picture that I had brought a sweater and I was skinny. I wore clunky boots for hiking. I don’t quite remember what the house in Fusagasugá was like, except for the bedroom and the thick, overstuffed quality of the mattresses. I remember drinking a beer and how it tasted and that it cost a nickel, while pineapple soda cost twenty centavos. I remember buying oranges from an urchin on the road. I remember later sleeping at a monastery on the floor. I remember playing cards with Ecuadorians and drinking aguardiente all night.

Just five years ago, when I planned a trip back to Colombia, people warned against travel there. Friends offered to buy me emergency equipment, like a hand-crank radio in case I was kidnapped in the jungle. I couldn’t convince them that Colombia is a developed country. Going there is probably safer than driving to Indianapolis.

And when I arrived, I recognized nothing except the corner of a park where we had gone to the flower exhibition, and I wasn’t even sure about that. Bogotá was an entirely different city. The world had changed, shed its skin entirely. All that was left of the Colombia I knew was within my faulty memory.

If I ever find the key to open the door to past memories, there is nothing to guarantee that what I find there is real. Now, you can take this as a sign of despair or one of liberation, but the words of my favorite Old Testament book, Ecclesiastes, come readily to mind: “Meaningless! Meaningless! Utterly meaningless! Everything is meaningless.”