Your mom died.

Your mom died.

Nobody cares.

It probably seems like a big deal to you. It might seem like an overwhelming, life-changing deal to you. Yet nobody cares. They even persist in laughing at movies, playing ball in the park, and going for ice cream.

It’s outrageous.

When our private moments of joy and grief are made public, we may find empathy among strangers. But should we demand it?

The first time you had margaritas and a chimichanga at Chi-Chi’s, you delighted in the spontaneous regaling of another table’s happy birthday. The final time you went to Chi-Chi’s, you could not enjoy your meal due to the incessant, automatonic regaling of every single god damned table’s birthday.

Actual Mexicans like to fire pistols in the air. It’s their way of expressing happiness. But their joy is not shared. Some people enjoy exploding novelty ordnances. It’s their way of celebrating American Independence. Or so they say. After a few months of celebrating one day in July, some neighbors find the explosions less than joyous.

These examples demonstrate how much we’re irked by others having a good time. Maybe we’re more sensitive to others having a lousy time, but celebrations of bad times invite controversy, too.

Last month, I happened upon two published letters expressing exasperation about funeral processions. The first appeared in the News-Gazette, written by an outraged person who’d been driving within a funeral party:

“This letter is directed to the male driver who sped past my dear mother’s funeral procession on Route 130 heading north to Philo. I am praying for you. You are indeed a thoughtless, ignorant and mean-spirited human being. (Perhaps moron is a better description).

There’s no additional information describing the effrontery behavior. Did the guy flip off the hearse? Did he spit on someone? Did he pass them on the shoulder?

We don’t know.

The author of this letter has an unlisted Champaign phone number. I’m not sure I would have interrupted her grieving to discover details. Frankly, it’s beside the point.

The second letter came from an exasperated driver from without the funeral party. He wrote to Slate’s Agony Aunt, Dear Prudence:

When a large number of non-funeral vehicles, including commercial trucks, etc. accumulated behind the party and it became clear they were not turning off any time soon, people began passing, very slowly, to continue on their way. Then some guys in the funeral party took offense at this perceived slight and blocked both lanes to keep anyone else from passing the procession which went on for several more miles.

Prudie advised Driver #2 to “chalk up the rudeness of the people in the procession to being overcome with grief.”

A different Agony Aunt approached the question ab initio, because nobody cares what she thinks. “All of us should always treat funeral processions with respect, out of common decency,” is the sort of advice you’re likely to get from women who look like Shirley Ann Parker.

A different Agony Aunt approached the question ab initio, because nobody cares what she thinks. “All of us should always treat funeral processions with respect, out of common decency,” is the sort of advice you’re likely to get from women who look like Shirley Ann Parker.

The funeral procession invites accidents and insults. It tells the entire outside world “whatever you’re doing, it will wait for us.” People get hurt. When you try to stop the flow of traffic on an interstate highway, people get killed. Even the trained escorts get killed. In response, Death Business profiteers seek more restriction of your freedom of movement.

I take the other road. I propose the tradition of the funeral procession be laid to rest.

GOVERNMENT SPONSORED IMPOSITION OF CULTURE

In Illinois, the funeral procession is protected by law.

(625 ILCS 5/11‑1420)

Sec. 11‑1420. Funeral processions. (d) The operator of a vehicle not in a funeral procession may overtake and pass the vehicles in such procession if such overtaking and passing can be accomplished without causing a traffic hazard or interfering with such procession.

This makes perfect sense in a perfect world, i.e. a world in which all roads have four lanes and no mourner “perceives a slight.” But you’ll notice that many roads are not four lanes across. Illinois 130, for example, is not four lanes in width. Some funeral directors are not able to route from service to graveside without bottlenecking a major thoroughfare.

If there were no such thing as a funeral procession, there would be no confusion over proper funeral procession etiquette.

The late Nobel Economics laureate Milton Friedman, a favorite of conservatives for the last half-century, correctly identified the purpose of government: to protect you from your neighbors.

(The other speakers accompanying Friedman are fellow conservative talking heads Linda Chavez and David Brooks. It’s from a series of 80s teevee programs about Friedmanomics which you should totally watch, if only to cackle about the fashions.)

Ronald Reagan made the same point, back in 1975 when he was still considered somewhat visionary:

There is a legitimate need in an orderly society for some government to maintain freedom or we will have tyranny by individuals. The strongest man on the block will run the neighborhood. We have government to insure that we don’t each one of us have to carry a club to defend ourselves.

These two agree: Government should protect you from others. Government should not protect you from yourself.

How then, do we rationalize the funeral procession? It’s a government mandated, government organized imposition on everyone’s freedom in favor of one person. And that person is dead.

The procession does not protect anyone. It’s just a ritual. Friends and family can drive from churches to cemeteries without forming an unbreakable chain. If they don’t know the route well, maps and GPS will help. But because funeral processions still exist, and are codified into our public traditions, they allow for an extra and unnecessary way for people to take umbrage, and get uppity.

What if your passenger is having a heart attack? What if she’s in labor, or anaphylactic shock? Well, just hope you don’t spot a hearse on your route to the hospital.

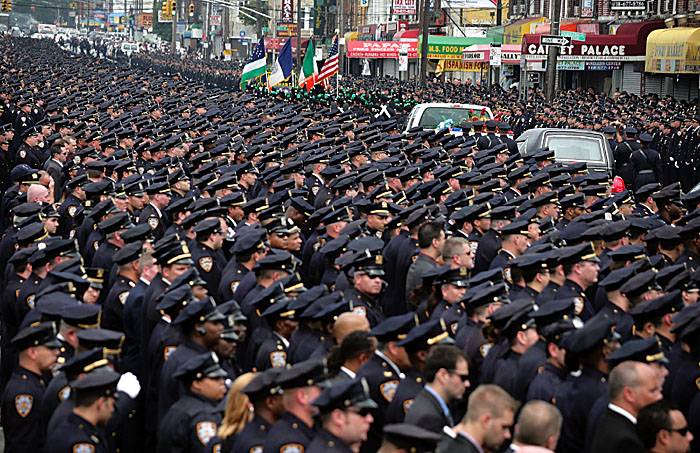

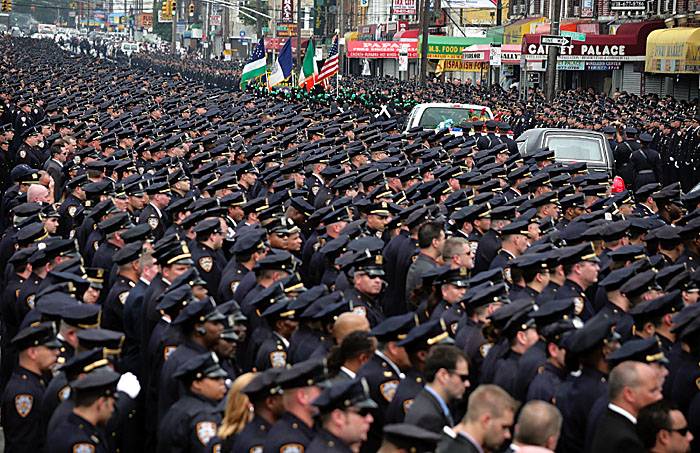

COP KILLED!

The tradition is especially bad for the perception of the police community.

We’ve all heard the ominous phrasing “three people were killed, one of them was a cop!” We can infer, in every instance, that the speaker is also a badge wearer. The phrasing incites us non-law enforcement types to ponder “are cops more important than other people?” The frequency of this utterance/pondering derives from the fact that cops gravitate toward danger in a way that plumbers don’t. Perhaps you’d hear “three people were killed, one of them was a plumber!” if plumbers had compulsory first-responder duties. Cops are no more self-absorbed than anybody else. It’s rather that everybody is self-absorbed.

But favoritism among police is especially galling, because they have guns. They command the rest of us, and in some cases they are not within their rights to do so. But we don’t argue with people who have guns. The criminal justice system has a bias which favors the word of law enforcement over the accused.

Worse, we know that cops will overlook the crimes of other cops. Wearing a badge entitles the wearer to a degree of lawlessness not afforded to the lay person. Whether the Thin Blue Line operates to get a cop out of a DUI, overlooks his sexual harassment or violent assault, it makes a mockery of the rule of law.

Some people become cops because they like to help others. For a lot of cops, it’s what their dad did — and they just kind of fell into it. But there’s a percentage who became cops because they like to push other people around.

The law enforcement community needs no further public ritual to remind us that they are more important than doctors, more important than water company safety inspectors, and more important than ambulance drivers.

PLENTY OF PLACES THAT ARE NOT PUBLIC ROADS

I’ve learned, through my own experience, that it’s possible to grieve and celebrate the dead without involving outsiders, and without forcing the public to divert from their own lives.

Two significant people died last weekend. They were significant to me, and I believe they were significant to the world and humankind. But I would not impose that notion on anyone. Not everyone was lucky enough to study the law of Property with John Cribbet. Some never had the chance to record or perform music with Jay Bennett. I’m lucky. I got to do both.

I attended the Cribbet memorial service Saturday afternoon at the law building. Lots of Very Important People did, too. Coach Lou Henson was there. The Chairman and CEO of State Farm was there. Chancellor Richard Herman spoke, as did president-emeritus Stanley Ikenberry. Mere judges and elected officials seemed commonplace.

It was an excellent service. Criminal Procedure legend Wayne LaFave had the crowd in stitches as we all fondly remembered the long life well-lived by a gracious man. And then many of us shed a tear when law staff pulled aside the black curtains to reveal a soldier, standing alone in the courtyard, bugling TAPS.

Vehicular traffic on Fourth and Pennsylvania moved normally throughout the afternoon. It seemed as if we could honor the larger than life figure even without bothering others.

I’ve never known anyone to respond to an oncoming funeral procession with anything other than mild dismay. “What a hassle,” seems to be the universal reaction. So why do we still do it?