Poverty is wealth.

To hoard wealth is to be poor.

Be content with what you have;

Rejoice in the way things are.

When you realize there is nothing lacking,

the whole world belongs to you. – Tao Te Ching, verse 44

Osama bin Laden was born into privilege. He had a private education, rode black stallions, played football, watched Maverick on TV and inherited money. He claimed to give it all up, funding terrorism and seeking to wrest all traces of comfort and culture from the already poor. But he spent the last days of his life almost as he had begun, isolated in a large suburban house, watching television and drinking Coca-Cola.

Osama bin Laden was born into privilege. He had a private education, rode black stallions, played football, watched Maverick on TV and inherited money. He claimed to give it all up, funding terrorism and seeking to wrest all traces of comfort and culture from the already poor. But he spent the last days of his life almost as he had begun, isolated in a large suburban house, watching television and drinking Coca-Cola.

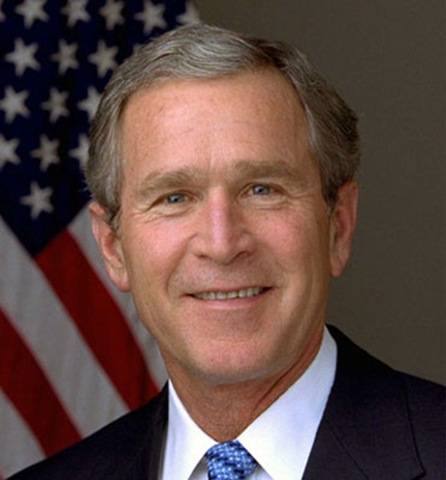

George W. Bush also was born into the moneyed class. He was so incapable of understanding the poor, he sought counsel from his minister on the subject. His father had never seen a grocery store scanner. His mother thought New Orleans refugees were “better off” herded into the Houston football stadium. When terrorists struck the World Trade Center, George’s advice to America was to “go shopping.” When he retired, his plan was to return home to “fill up the old coffers.”

George W. Bush also was born into the moneyed class. He was so incapable of understanding the poor, he sought counsel from his minister on the subject. His father had never seen a grocery store scanner. His mother thought New Orleans refugees were “better off” herded into the Houston football stadium. When terrorists struck the World Trade Center, George’s advice to America was to “go shopping.” When he retired, his plan was to return home to “fill up the old coffers.”

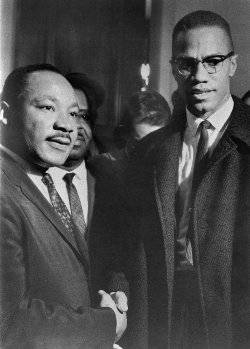

Martin Luther King Jr. was well educated and came from a more comfortable home than the majority of black Americans. He preached integration into the white society of wealth. Malcolm X was a child of the streets, poverty, and prison. He preached black nationalism, but later renounced the idea of racial separation, and what he gave the civil rights movement (that MLK did not) was a sense of the value of black culture and identity apart from the prevailing society of privilege and power.

Martin Luther King Jr. was well educated and came from a more comfortable home than the majority of black Americans. He preached integration into the white society of wealth. Malcolm X was a child of the streets, poverty, and prison. He preached black nationalism, but later renounced the idea of racial separation, and what he gave the civil rights movement (that MLK did not) was a sense of the value of black culture and identity apart from the prevailing society of privilege and power.

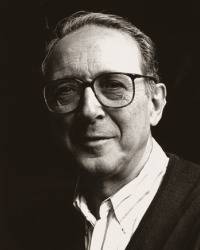

Liberation theologian Jon Sobrino lived in El Salvador for 50 years. In his collection of essays, No Salvation Outside the Poor, he writes of “the civilization of poverty” as the only means whereby “the mystery of reality breaks through, the very reality of God breaks through.” He also writes, “Any society that claims to be truly ‘democratic’… must be conceived and organized on the basis of the rights of the disadvantaged,” and “it is poverty that really leaves room for the spirit.”

Liberation theologian Jon Sobrino lived in El Salvador for 50 years. In his collection of essays, No Salvation Outside the Poor, he writes of “the civilization of poverty” as the only means whereby “the mystery of reality breaks through, the very reality of God breaks through.” He also writes, “Any society that claims to be truly ‘democratic’… must be conceived and organized on the basis of the rights of the disadvantaged,” and “it is poverty that really leaves room for the spirit.”

“Affluent countries have no hope,” he writes, “but only fear.”

Author David Foster Wallace told Fresh Air’s Terry Gross, in an interview before his suicide in 2008, how he and his “ridiculously overeducated” friends struggled with meaning and purpose in life. His writing pursued every avenue, every digression, every possible outlook, footnoting copiously and trying to encompass what he could perceive of our consumer society. His brilliant, final, unfinished novel, The Pale King, went to the very beating heart of American culture, the IRS system and the way money moves us, manages us and engulfs our very consciousness. (1)

Author David Foster Wallace told Fresh Air’s Terry Gross, in an interview before his suicide in 2008, how he and his “ridiculously overeducated” friends struggled with meaning and purpose in life. His writing pursued every avenue, every digression, every possible outlook, footnoting copiously and trying to encompass what he could perceive of our consumer society. His brilliant, final, unfinished novel, The Pale King, went to the very beating heart of American culture, the IRS system and the way money moves us, manages us and engulfs our very consciousness. (1)

There is something obscene in the fact that my cell phone bill runs $265 a month.

Syndicated columnist Cal Thomas usually writes about abortion, religion, so-called conservative family values, and anything anti-Obama. A few weeks ago he tub-thumped for the movie version of Ayn Rand’s 1957 doorstop of a book, Atlas Shrugged, a book that preached Rand’s atheistic, libertarian, “virtue of selfishness.” To Rand (and apparently to Thomas despite his avowed religiosity), an unfettered free market, capitalism, and money itself are the true godhead trinity. “Go see it,” Thomas wrote.

Syndicated columnist Cal Thomas usually writes about abortion, religion, so-called conservative family values, and anything anti-Obama. A few weeks ago he tub-thumped for the movie version of Ayn Rand’s 1957 doorstop of a book, Atlas Shrugged, a book that preached Rand’s atheistic, libertarian, “virtue of selfishness.” To Rand (and apparently to Thomas despite his avowed religiosity), an unfettered free market, capitalism, and money itself are the true godhead trinity. “Go see it,” Thomas wrote.

In contrast to the “civilization of wealth” that Thomas champions, another liberation theologist, Ignacio Ellacuria, talked of “the civilization of poverty” as one of “a universal state of affairs which guarantees the satisfaction of basic needs, the freedom of personal choices, and an environment of personal and community creativity that permits the emergence of new forms of life and culture, new relationships with nature, with others, with oneself, and with God.”

Sofia Coppola’s elegant and entrancing new film, Somewhere, depicts our culture’s highest echelon of attainment ― what it means to be movie star royalty. Stephen Dorff portrays the young actor, obscenely paid, pampered around the world. Everything is his for the asking: the royal suite at Italian hotels with a built-in swimming pool, pole-dancing twins in his bedroom, fast cars, the adoration and accolades of the masses, everything available at his slightest whim. Sending his daughter off to boarding school, alone, he calls someone, perhaps his publicist, and breaks down. “I have nothing,” he says.

The story is told in the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke in the New Testament of the rich young man who wanted to find meaning in life. He had followed all the rules. He had done the right things. And he came to Jesus and asked, so what am I doing wrong? Nothing, Jesus told him. You are OK, but what you really have to do is sell your stuff, empty your bank account, and give it all away to the poor. Only then will you really have everything you want.

In another story, Jesus said to give your money to the government if they want it, without complaining.

So the young man walked away from Jesus, disturbed and very sad, probably as sad as the character in the Sofia Coppola movie. The very idea was unthinkable, and would be even to someone like Cal Thomas (who one presumes does read the Bible from time to time, but strangely may have overlooked that prominent story).

The answer was right there in front of him, but the man couldn’t do it. Maybe none of us can.

1. Chapter 19, pages 140–141, from The Pale King, by David Foster Wallace:

“But how did this alienated small selfish make-no-difference thing result from the sixties, since if the sixties showed anything good it showed that like-minded citizens can think for themselves and not just swallow what the Establishment says and they can bawl together and march and agitate for change and there can be real change; we pull out of ‘Nam, we get Welfare and the Civil Rights Act and women’s lib.’

‘Because corporations got in the game and turned all the genuine principles and aspirations and ideology into a set of fashions and attitudes-they made Rebellion a fashion pose instead of a real impetus.’

‘It”s awful easy to vilify corporations, X.’

‘Doesn’t the term corporation itself come from body, like “made into a body”? These were artificial people being created. What was it – the Fourteenth Amendment that gave corporations all the rights and responsibilities of citizens?’

‘No, the Fourteenth Amendment was part of Reconstruction and was intended to give full citizenship to freed slaves, and it was some corporation’s sharpy counsel that persuaded the Court that corporations fit the Fourteenth’s criteria.’

‘We’re talking C corps here, right?’

`Because it’s true-it’s not even clear now when you say corporation whether we’re talking about Cs or Ss, LLCs, corporate associations. plus you’ve got closely-held and public, plus those sham corporations that are really just limited partnerships loaded up with non-recourse debt to generate paper losses, which are basically just parasites on the tax system.’

`Plus C corps contribute by double taxation, so it’s hard to say they’re nothing but a negative in the revenue sphere.’

`I’m giving you a look of complete scorn and derision, X; what do you imagine it is we do here?’

`Not to mention fiduciary instruments that function almost identically to corporations. Plus franchise-spreads, flowthrough trusts. NFP foundations established as corporate instruments.’

`None of this matters. And I’m not even really talking about what we do here except in the sense that it puts its in a position to see civic attitudes close up, since there’s nothing more concrete than a tax payment, which after all is your money, whereas the obligations and projected returns on the payments are abstract, at the abstract level the whole nation and its government and the commonweal, so attitudes about paying taxes seem like one of the places where a man’s civic sense gets revealed in the starkest sorts of terms.’

‘Wasn’t it the Thirteenth Amendment that blacks and corporations exploited?’

‘Let me throw him off, Mr. G., I’m pleading with you.’

‘Here’s something worth throwing out there. It was in the 1830s and ’40s that states started granting charters of incorporation to larger and regulated companies. And it, was 1840 or ’41 that de Tocqueville published his book about Americans, and he says somewhere that one thing about democracies and their individualism is that they by their very nature corrode the citizen’s sense of true community, of having real true fellow citizens whose interests and concerns were the same as his. This a kind of ghastly irony, if you think about it, since a form of government engineered to produce equality makes its citizens so individualistic and self-absorbed they end up as solipsists, navel-gazers.’