Parasol Records recently announced they were shutting down the mail-order portion of the business as of December 17th. For many music afficiandos, musician and fan alike, it marked the end of an era.

Parasol Records recently announced they were shutting down the mail-order portion of the business as of December 17th. For many music afficiandos, musician and fan alike, it marked the end of an era.

In 1991, owner Geoff Merritt started sending records all over the world. Parasol’s twenty-plus years of service to music fans became an invaluable tool for independent musicians worldwide, extending the reach of their work to places, at that time, the artists could not fathom. That role, however, has been severely undercut by the rise of the Internet and the digital music revolution. Those factors have made the distribution service’s downfall seem inevitable, to those within the company, as well to outside observers.

‘I always wanted to own a record store.’

Though Parasol officially began June 1, 1991 the idea for the store originated earlier. That’s Rentertainment, the movie rental store on campus owned by Merritt, began its life renting records rather than movies.

“I always wanted to own a record store,” Merritt said. “When Rentertainment started, it was a record rental store before it was a video store. Then the record industry told us we couldn’t do that anymore so we sold all of the records.”

After their record liquidation, Merritt could not get working with music off his mind. To scratch his itch, he began selling records out of his apartment and out of magazines – “really small scale,” he explained.

Selling music out his own residence “got weird,” however, leading him to purchase a house not far from the current Parasol location from which he could sell music, it marked the official start of Parasol. It was also the beginning of the Parasol and Mud labels, while a friend ran a label called Bus Stop out of the same house.

“When we first started, we weren’t really part of the ‘Industry.’ We were buying and selling stuff by labels that were tiny,” Merr

itt said. As the indie-rock scene blossomed in the ‘90s, Parasol was there to make music from labels like Sarah, Creation and countless other small labels available far beyond their own limited scope.

The mail-order service didn’t offer any major label albums and the primary form the albums took was vinyl, whether it as a seven-inch, 12-inch or flexi-disc, specializing in “jangly pop” from all over.

“We’d sell to stores in the states and all over the world,” Jim Kelly explained. Kelly has worked at Parasol for most of its existence and currently serves as manager for the Parasol label. “A lot of our distributorship used to involve shipping to a handful of record stores in Japan. They would place extremely large orders, and for any stuff coming out of the US or UK, we were a one-stop shop. The Japanese were big fans of Parasol for a while.”

The times they are a’ changin’

At Parasol’s peak, customers were rabid for the music Parasol, and other outlets like them, could offer. Merritt explained that Japanese record stores used to send a buyer to tour stores in the US to purchase music to sell in Japan.

“He would come in to Parasol and buy $2,000 worth of stuff and put it in boxes and ship it back to Japan, then go on to Chicago and do it again,” he said, before adding, “I don’t hear of stuff like that going on anymore.”

Big orders and big overseas spenders slowly lessened as the industry shifted. This caused a shift in the way Parasol did business as well. Not only did the selection expand beyond vinyl albums to include CDs, but releases from small labels were accompanied by major labels as they began to take notice of indie bands.

“[We’ve seen] CDs come and vinyl come back. Now the cost of entry of making a CD has come way down and now everyone can make a CD,” Merritt said. “How people make and get their music has changed considerably. It’s not digging through record bins in record stores anymore. It’s a whole lot easier today than it is when we started.”

Currently, digital sales for albums make up one-third of the industry today, making it very difficult for businesses like Parasol to remain open. As time went on and the industry continued to shift, it became more and more apparent to Merritt the “colorful people” who were his in-store customers could not keep the many parts of Parasol moving. In order to keep going as a record label, something had to change and the mail-order and store operations were the casualties.

“It’s a little bittersweet, but it’s the right thing to do and the right time to do it. We work very hard on the label and with Rentertainment and everything else going on we just couldn’t keep doing it. We could do a half assed job doing it all or we could rein it in and do a better job putting out records, which is what I really like to do,” Merritt said. “It would be more bitter if we were closing the whole operation down – I don’t think we’ll ever do that.”

Parasol is dead. Long live Parasol.

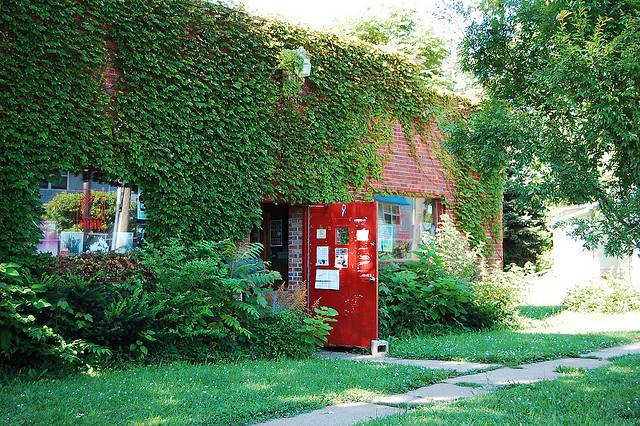

As of December 17, the building at 303 West Griggs Street will no longer house any storefront or distribution center, but the building will remain the home of the Parasol label.

As of December 17, the building at 303 West Griggs Street will no longer house any storefront or distribution center, but the building will remain the home of the Parasol label.

While asserting their affinity for their customers and their gratitude for their business, Merritt and Kelly each identified working with the label as the best part of their jobs. Whether promoting the music of local bands like Elsinore or You & Yourn (among many others) or signing wonderful foreign bands to their roster (like The Soundtrack of Our Lives or Peter Bjorn & John), Parasol has always provided the community with music and enriched the music scene in Champaign.

“The labels are still going strong,” Kelly said. “We’ve had to streamline, and it’s sad [the store] won’t be around anymore, but it gives Geoff and I a chance to focus on the labels and look for the artist who needs a push to be more famous, or whatever.”

Already the label has lined up a busy slate of releases and projects for 2012. Parasol will not just be a behind-the-scenes presence, though. Neither Merritt nor Kelly know exactly what will become of the space the store currently uses but both expressed in interest in hosting concerts in the space.

“[Shows have] been the most fun for us. I wouldn’t be surprised if in the future, once a month or once a quarter, we host shows. The shows are always awesome,” Kelly commented.

Parasol has given the CU music scene a immeasurable boost in its twenty-plus years of existence. Looking back on that time, Merritt played down the role of his business in aiding local music, but acknowledged the impact Parasol has had.

“There has always been an amazing music scene in CU, there’s always been people who contribute to it as a musician or label or venue or just bands,” he said. “I wouldn’t say the scene wouldn’t exist without us, because it would and someone would do what we’re doing, but I’m glad we were here to help out. We’re just one little part of this huge thing that is the CU scene. And it’s an awesome scene, always has been.”

Merritt’s humility downplays the role his business has played in the community. Another business owner, Jeff Brandt of Exile on Main Street, was able to exalt Parasol fittingly, however. Though the two businesses are technically competitors, Brandt explained that he never viewed Parasol in that way.

“They’re another store I can recommend to people if we don’t have what they’re looking for,” he said. “I worked at Periscope for years and it was the same thing. No one looked at them as competition – it was like a symbiotic relationship among record stores. It’s unfortunate that they had to go out of business. Twenty-plus years is a great run and it won’t be easy to let something like that go.”

Indeed, it will not be easy for Merritt, Kelly or any of Parasol’s customers and fans to let go. But the label is intact, and perhaps able to serve CU even better than before. With the commitment of those still working at Parasol another twenty years of providing CU (and the world) with great music seems entirely likely.