This Wednesday night, the Krannert Center for Performing Arts hosts the Grammy Award winning Carolina Chocolate Drops. The Chocolate Drops formed in 2005 after meeting serendipitously at the Black Banjo Gathering in Boone, North Carolina. That meeting seems almost miraculous considering the divergent paths that founding members Rhiannon Giddens and Dom Flemons took getting there. Flemons is from Phoenix, played percussion in his high school marching band, and found his way to American roots music by tracing a thread from the Beatles to Dylan to Chuck Berry and eventually into pre-war music. He sights Mike Seeger, the great revivalist, as an early inspiration to his approach to traditional music.

While Flemons’ musical chops were earned busking and in coffee shops, Giddens is classically trained. She graduated from Oberlin Conservatory in Ohio, where she specialized in vocal performance — opera singing! Opera performance is, of course, an art form requiring tremendous discipline and time, but Giddens was devoted. She performed in five different operas with lead roles in three of them. She began attending weekly contra dances as a way to decompress from that world, and found a vibrant and meaningful community there. So, she started to work her way into it, first by learning the fiddle, and then by collaborating in various musical folk and roots endeavors with friends and family.

As much as the Black Banjo Gathering was a watershed moment for Flemmons and Giddens, it was even more so for those of us interested in the recovery of American traditional music. The project that emerged from their meeting would eventually shape itself into the Carolina Chocolate Drops, a band unique first in its reclamation of “old-time” as part of the African American vernacular musical tradition, and second in their ability to win new audiences with that music. In a few years, they were headlining folk festivals, playing internationally, and had a record out on the respected Nonesuch label.

As much as the Black Banjo Gathering was a watershed moment for Flemmons and Giddens, it was even more so for those of us interested in the recovery of American traditional music. The project that emerged from their meeting would eventually shape itself into the Carolina Chocolate Drops, a band unique first in its reclamation of “old-time” as part of the African American vernacular musical tradition, and second in their ability to win new audiences with that music. In a few years, they were headlining folk festivals, playing internationally, and had a record out on the respected Nonesuch label.

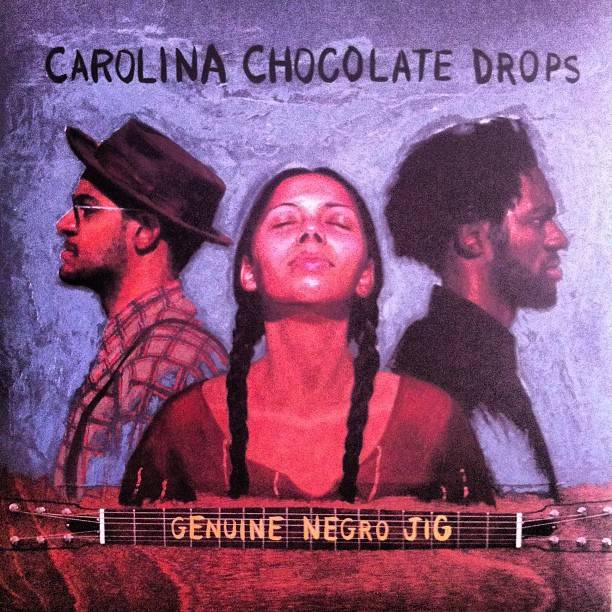

That record, 2010’s Genuine Negro Jig (above left), won the Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album. The band has seen a few personnel changes since then: original member Justin Robinson left the band in 2011, and multi-instrumentalist Hubby Jenkins and beat-boxer Adam Matta joined. Giddens sites these changes as part of the life-blood of the band — new collaboration helps to keep things fresh. The other part of the band’s success might be attributed to the dichotomy between Giddens and Flemons’ approach. Her training in the opera has given her a flare for the dramatic, an acute sense of the importance of playing to the audience, as well as an ear for technique.

Flemons brings a free spirit to the music and scholarly devotion to the tradition. The balance they strike has been very productive indeed. This is the second time the band has played Krannert in recent memory. Last Fall, the band opened for Taj Mahal as part of the Ellnora Guitar Festival, and if it’s possible to upstage a legend, they did it. The Chocolate Drops’ set was as powerful as it was generous and if Wednesday’s performance is anything close to that wonderful night of music, we’re in for a treat. As I alluded to above, the band’s approach to the old-time tradition isn’t to replicate it, but to create fresh inroads to 80-year-old songs. They then backwards engineer that process in order to imbue traditional sensibilities into contemporary songs.

What impresses me most about the quartet of players, however — and what I look forward to in this week’s performance, is the careful curation of a few teaching moments during their performance. For example, they are likely to play songs from the American minstrel tradition, that bleak 100-year period stretching roughly from 1830–1930, when the most popular form of entertainment in this country was white men in blackface (and sometimes black men in blackface) putting on comedic musical theatre based around racist exaggerations and projections.

What impresses me most about the quartet of players, however — and what I look forward to in this week’s performance, is the careful curation of a few teaching moments during their performance. For example, they are likely to play songs from the American minstrel tradition, that bleak 100-year period stretching roughly from 1830–1930, when the most popular form of entertainment in this country was white men in blackface (and sometimes black men in blackface) putting on comedic musical theatre based around racist exaggerations and projections.

Minstrelsy represents everything that mainstream America now wishes to forget about itself (I doubt there’ll be mention of it being one of Abraham Lincoln’s favorite forms of entertainment in the new Spielberg movie). But the last time I saw them, Flemons and Giddens both took a moment to relate why the recovery of the music from the period is important to their creative and intellectual project and should be important to the wider study and appreciation of American music as well.