In the fifteen years that Polyvinyl has been a record label, it’s fair to say that everything has changed. The record industry of the 1990s was an ever-expanding, money-making behemoth that pushed its latest self-selected band through the media grinder and hoped for a hit. Alternatively, independent artists could slowly build buzz for themselves through touring and word of mouth, eventually catching on with a mid-sized label. In today’s world of instant access, the buzz usually comes first, and then the labels mostly play catch up. This model requires new equations for success. Given the huge losses suffered by the major labels over the last ten years, we all know how their decisions turned out. But independent labels have remained amazingly resilient by embracing change.

In the fifteen years that Polyvinyl has been a record label, it’s fair to say that everything has changed. The record industry of the 1990s was an ever-expanding, money-making behemoth that pushed its latest self-selected band through the media grinder and hoped for a hit. Alternatively, independent artists could slowly build buzz for themselves through touring and word of mouth, eventually catching on with a mid-sized label. In today’s world of instant access, the buzz usually comes first, and then the labels mostly play catch up. This model requires new equations for success. Given the huge losses suffered by the major labels over the last ten years, we all know how their decisions turned out. But independent labels have remained amazingly resilient by embracing change.

Polyvinyl continues to thrive because it emphasizes its artists. The key is the personal relationships that bands feel to the staff, and the sterling reputation that founders Matt Lundsford and Darcie Knight have built for the label. As I spoke with Matt on a recent sun-drenched afternoon in downtown Champaign, it was easy to see why so many bands find the label accessible and genuine.

So(o) Young

Though it’s now known as a Champaign record label, Polyvinyl did not originate here. The label spent its formative years in the indie-rock mecca that is Danville, IL. This is slightly sarcastic, but it is also a point about how like-minded people in small towns throughout North America were able to spread the word about good music even before the dawn of the internet. Every small town had a group of kids who, for whatever reason, sought out music apart from the same fifteen songs played on MTV in perpetuity. In the eighties and nineties, the predominant means of communication was the zine, a hand-crafted labor-of-love that would often include reviews, features, artwork, comics and just about anything else one could think of. It was a way for an individual to promote the work they loved. And that’s exactly how Matt and Darcie started Polyvinyl, when they were just out of high school.

I was super fortunate to have friends and a girlfriend who were super excited about music and the scene that was happening in the 90s, especially in the Midwest. Even though I grew up in a pretty small town with the typical small-town adolescence, we had friends putting on DIY shows, renting out VFW halls and other community buildings. At that time the Champaign-Urbana scene was just in a great place and it spilled over to the whole region. Bands from Champaign would play shows here and we’d go to shows all the time.

I was super fortunate to have friends and a girlfriend who were super excited about music and the scene that was happening in the 90s, especially in the Midwest. Even though I grew up in a pretty small town with the typical small-town adolescence, we had friends putting on DIY shows, renting out VFW halls and other community buildings. At that time the Champaign-Urbana scene was just in a great place and it spilled over to the whole region. Bands from Champaign would play shows here and we’d go to shows all the time.

It got to the point that we wanted to support things in some way. It was pre-internet, so the choices at that time were to make a photocopied fanzine, put on shows, sell records out of crates at the back of shows. This is how people would learn about bands, and we did all three of those things for a long time.

From that we started doing anything we could to be proactive and exciting. It all felt fun. We really liked these bands and we were friends with a lot them and we wanted to do all we could to support them.

Originally Matt and Darcie followed the zine model as a way to share their thoughts on music and promote their favorite acts. Like many others before them, they realized that the zine was limiting, in that you could share words and words about great music, but you could not share the sound. In those days, if you wanted to share music you couldn’t just pop an mp3 or stream on your blog. You had to offer physical product. And musical commerce for individual songs in the 90s was still the 7″ record.

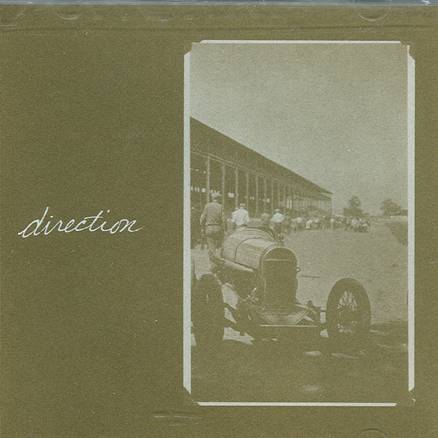

The first record we ever put out was a split 7″ to go inside the zine. At the time, it just seemed like a great way of furthering the fanzine. We had Back of Dave from near St. Louis and another band called Walker from Lafayette, Indiana. It was so exciting to do that — to release music by these bands we liked. I mean, I still think about how great Back of Dave was. And doing that really sparked the interest of Darcie and I, because we enjoyed that process so much. After we put out that 7″, the fanzine lasted two more issues, including this compilation called Direction that we put together with like twenty bands on it. The compilation was a jumping off point for the label.

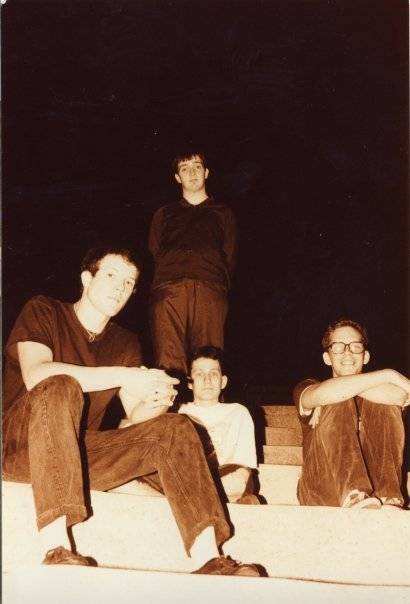

One of the keys to the label’s growth was befriending a new band out of Champaign who shared Matt and Darcie’s DIY spirit and was turning a lot of heads from the beginning. That band was Braid.

One of the first five things we put out was a repress of their first 7″. They had run out of copies, so we repressed it for them. Then we released a couple of more of their 7″s . The guys in Braid were really interested in the opportunity to have product to sell and go on tour. Because they worked so hard, those 7″s began to just sell and sell. Eventually, they put out an album, Frankie Welfare Boy, on their own, but we were helping them to promote and distribute it. And then things started to grow and they were touring all over the place. From that point, things just naturally evolved into releasing albums.

grow and they were touring all over the place. From that point, things just naturally evolved into releasing albums.

After developing a relationship with Braid and releasing their albums, culminating with the release of Frame and Canvas, the label started picking up more acts in a similar manner — by getting to know the bands and giving them opportunities. Though Braid and Polyvinyl worked together on and off in the early days in a very informal way, the first truly active band on their label was Rainer Maria, a band that had been featured on the fanzine Direction compilation.

There was really such a great pipeline of bands in that time where people would trade shows here and there. C-U bands would play in Ann Arbor. It was a different era, people weren’t nearly so interconnected. The networking then was so primitive that we would not have known about a band until we actually saw them.

We got to know Rainer Maria because two of the members played a show in Urbana with their old band. We started to keep in touch with them by email since they were from Madison. They got in touch about their new band Rainer Maria and we started with them from the absolute very beginning. It was a situation where it was a perfect partnership. They were interested in working hard. Darcie and I at the time were looking at the label and realizing that we wanted to take a step to make this a full-fledged th ing. Their records got out there and started to sell. Their shows got bigger and then the label started to get a little bigger. We both grew very naturally together.

ing. Their records got out there and started to sell. Their shows got bigger and then the label started to get a little bigger. We both grew very naturally together.

For Sure

Despite the success of Braid and Rainer Maria, Polyvinyl’s best-selling album from the 90s might actually be American Football’s self-titled release. This is a fact that may surprise many locals, especially considering how infrequently that band is cited in discussions of the C-U scene over the last twenty years. But the album, originally released in 1999, has been the definition of slow grower, growing in stature as the years have passed, with a lineup that included Mike Kinsella (Cap’n Jazz, Joan of Arc), Steve Holmes and drummer Steve Lamos (one of the best drummers to ever live in this region).

With the success of these three bands helping to stabilize the label, Darcie and Matt began to expand their roster to bands outside of the Midwest and beyond a pretty specific sound.

And then we got established and started to work with new bands. Bands that we liked, and then some of our touring bands, would make suggestions. We started to work with a roster that got wider and spread out across the country. Our first west coast band was Sunday’s Best.

As the label grew in success and continued to expand, so did the need to solidify the business aspects. From the get go, Lunsford claims his label always worked to create relationships that worked for everyone.

This thing grew from such a friendship/hobby thing that we’ve sort of learned as we’ve gone along. We’ve approached the business side of things as we love doing this, so we have to make a contract so everyone knows what the parameters are. Our contracts are drawn up so it’s equal parts our responsibility to the artist and their responsibility to the label. We’re not locking anyone down to profit from all their rights.

We came from a simple model that was made popular by Dischord, which is a 50/50 profit splitting arrangement. We want to be in a true partnership with our bands. It’s a situation where it’s not tricky major label economics. It’s pretty straight forward so that everyone understands. We do it in a manner so that, if the band and the label are both equally working hard, they both benefit equally.

We came from a simple model that was made popular by Dischord, which is a 50/50 profit splitting arrangement. We want to be in a true partnership with our bands. It’s a situation where it’s not tricky major label economics. It’s pretty straight forward so that everyone understands. We do it in a manner so that, if the band and the label are both equally working hard, they both benefit equally.

Though most independent labels try to keep things very transparent, there are stories of bands going back to get unpaid royalties from their labels. In 2005, Green Day famously closed indie Lookout Records by taking over possession of their back catalog. In other cases, bad blood between the label and the artist has led to arguments in the press, but Polyvinyl has managed to keep things copacetic with their artists.

I’m really proud to say that we’ve never had any artists come back years later. We’ve always kept everything above the board. We’ve seen a ton about those sorts of things. And there’s all those situations where pitfalls come with successes. We’ve been very careful to learn from everyone else.

Climb the Ladder

In the last ten years, the label has continued to grow and evolve. They opened up a West Coast office in San Francisco with three employees, headed up by former local Seth Hubbard who handles the label’s press contacts. And last year the head of European distribution moved from Champaign to New York, so they have an unofficial office there as well. The label now has an international roster that includes bands from Australia (Architecture in Helsinki), Norway (Casiokids) and Sweden (Loney, Dear and Love is All). Many of their bands have had break-out successes, like Mates of State, Architecture in Helsinki and Japandroids.

However, nothing has changed the scope of the label over the past six or seven years like the success enjoyed by of Montreal, a well-known indie rock band whose popularity skyrocketed when they signed with Polyvinyl, and whose albums have sold well in excess of anyone else on the roster.

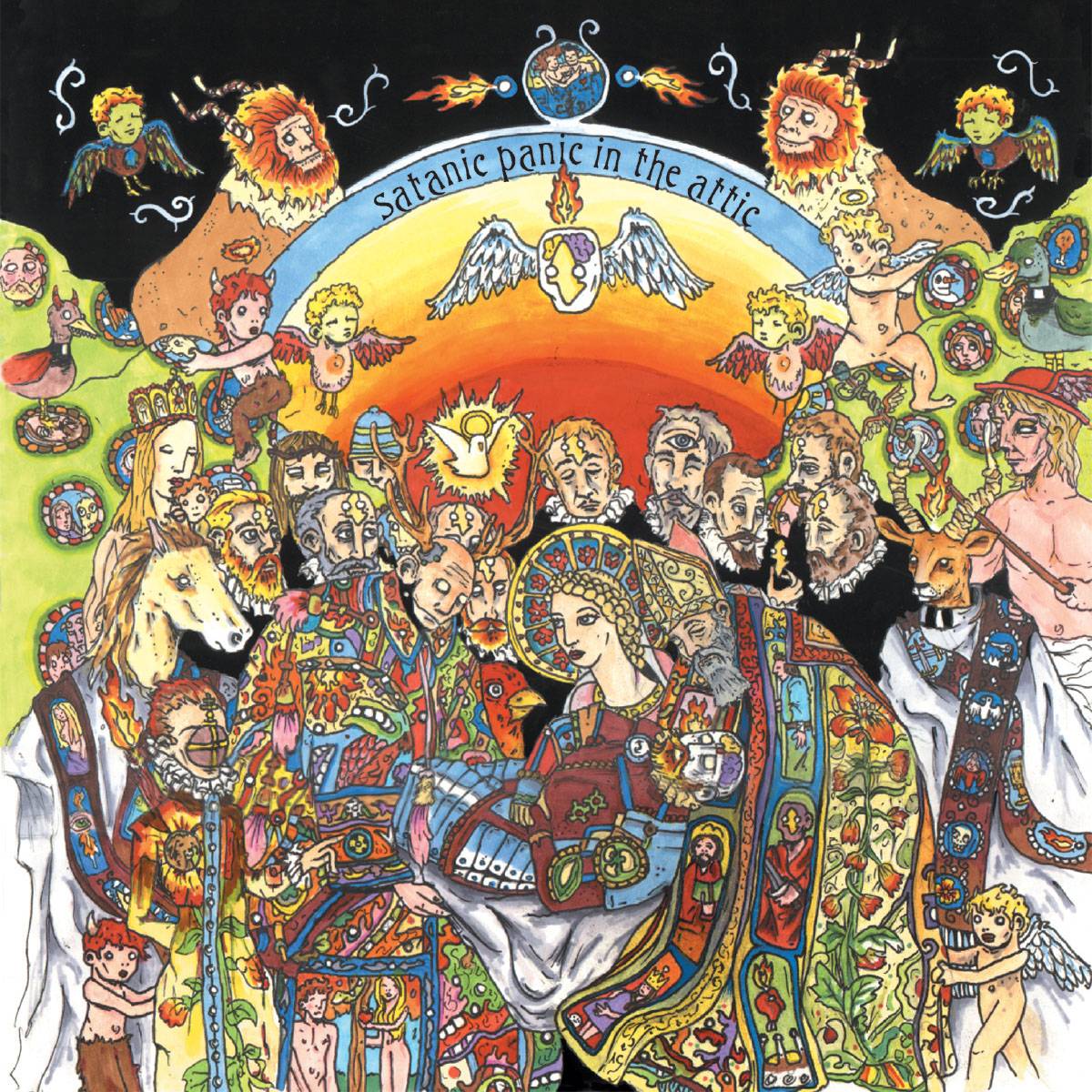

of Montreal came on board around 2004. Before that they were already established. When they came on with us, it was the perfect example of our profit-sharing business model working hand-in-hand with a band. They were super hard-working, even after being a band for such a long time. They always wanted to tour, and they had this ambition to grow their theatrical live performances by having a more supportive label. We got to know them through their booking agent at the time, who is a close friend of mine and of the label. He’s the kind of person who’s very passionate about the bands he books and wants to get the word out about his bands. We’d been talking with him and he sent us the Satanic Panic in the Attic album, and Darcie immediately loved it and wanted to release it. So we took a stab at putting it out.

of Montreal came on board around 2004. Before that they were already established. When they came on with us, it was the perfect example of our profit-sharing business model working hand-in-hand with a band. They were super hard-working, even after being a band for such a long time. They always wanted to tour, and they had this ambition to grow their theatrical live performances by having a more supportive label. We got to know them through their booking agent at the time, who is a close friend of mine and of the label. He’s the kind of person who’s very passionate about the bands he books and wants to get the word out about his bands. We’d been talking with him and he sent us the Satanic Panic in the Attic album, and Darcie immediately loved it and wanted to release it. So we took a stab at putting it out.

We worked hard on it, and it just did really well. It’s such a good album that came out at the perfect time for of Montreal. They had been established before that, but Satanic Panic just connected with so many more people. It was interesting because a lot of people were just getting exposed to them and didn’t realize how long they had been around and working hard. I think they are a good example of the importance of persevering in this industry.

of Montreal’s success continued as the band’s fan base expanded through word of mouth and through their outlandish stage performances. In January of 2007, of Montreal released Hissing Fuana, Are You the Destroyer?, a critical and commercial success that took the band and the label to another level of success. By a large margin, it’s the best-selling album in the label’s history.

People just really identified with that album. I think years from now people will look back at the record and appreciate it even more. It sold a fair amount more than the next-bestselling release.

With the close-knit relationships that come on smaller labels like Polyvinyl, it seems natural that some bands might wonder if the label is devoting too much time to their successful artist. After all, the label only has so many resources. So I asked Matt if of Montreal’s success led to any issues with providing support for the rest of the roster.

I think that’s the beauty of how the independent profit-sharing model works. If the label and the band are both doing well, you’re both equally putting time and resources into the project. We always try to match what the artists put in. of Montreal has always been working and touring at an incredibly high level, and we’ve been right there with them.

We look at it like that for all of our bands. We have never thought that one band is doing so fantastically that it should take away from the other efforts. That would be so unfair. It’s not the way we operate.

My Life

A similarity shared by many successful independent labels is the advantage of a home office in a medium sized college town. Jagjaguar/Secretly Canadian is in Bloomington, IN; Merge records is in Chapel Hill, NC. These towns share a relatively cheaper cost of living and renting space. And a population that is much more likely to support creative artists and strong music than typical mid-size towns. So, in many ways, it was probably inevitable that Matt and Darcie would make the move from Danville to Champaign. But they knew they were leaving behind a very supportive home town.

When Darcie and I were running the label in Danville, we had a tremendous amount of support. Support that I could never be thankful enough for, from our families and our friends. They were all incredibly supportive when we decided to do this as a career.

But we eventually rea lized that the two of us were going bonkers with work all the time, and we needed to put ourselves in a new position. So we knew we needed to find a community that had more of an infrastructure that would support the label. With the university and the community here, it was a very logical and reasonable choice to move here. We really felt that bringing the company to Champaign would prove to be a good move in terms of the resources that would be found here.

lized that the two of us were going bonkers with work all the time, and we needed to put ourselves in a new position. So we knew we needed to find a community that had more of an infrastructure that would support the label. With the university and the community here, it was a very logical and reasonable choice to move here. We really felt that bringing the company to Champaign would prove to be a good move in terms of the resources that would be found here.

Being here from a business point of view has been super rewarding because we’ve watched lots of our peer indie labels have various struggles with the higher cost of doing business. And just the logistics can be so much more difficult.

Despite running one of the top ten or fifteen independent record labels in the country, Lunsford’s daily routine could hardly be more mundane. He drives from the house he shares with Darcie in southwestern Champaign, drops his oldest son off at school, and goes to work in downtown Champaign. It’s a commute shared by a couple hundred other people. And that’s part of the reason he likes living here.

On a personal note, as a place to live, I think this is a great town. Darcie and I are really excited about raising our kids here. I think that after being around for fifteen years as a label, we really feel that the local community has given us a tremendous amount. I think that one of our goals in the next fifteen years is to work to support the community that has given us so much — to be more visible in the community in general.

No Locals

Polyvinyl has not had a huge roster of local artists throughout most of its history. After the initial success of Braid and American Football, the only local band on the roster over the last decade has been Headlights, who are currently inactive (and possibly done). When I ask Matt about the lack of local acts on the roster, his immediate reaction is of surprise. Not the surprise that I’d be willing to ask the question, but genuine surprise that the label currently has no active local acts.

I can see the point of view that we should have more local bands. I really do. But we’ve always tried to work with bands that we like really well, regardless of where they are at. At this point, we have several international bands. Whether we do or don’t have any local bands is, at any given time, something that’s completely unintentional. If we have a local band, it’s not because they are from here, it’s because we really like what they are doing. We try to keep the philosophy that if something that we really like comes along, we’ll work with them, regardless of where they are from.

I can see the point of view that we should have more local bands. I really do. But we’ve always tried to work with bands that we like really well, regardless of where they are at. At this point, we have several international bands. Whether we do or don’t have any local bands is, at any given time, something that’s completely unintentional. If we have a local band, it’s not because they are from here, it’s because we really like what they are doing. We try to keep the philosophy that if something that we really like comes along, we’ll work with them, regardless of where they are from.

There’s no doubting that Lunsford is authentic in this response. And Polyvinyl clearly does keep an eye on the local scene — they featured the local bands Take Care, Common Loon and Midstress (formerly The Fresh Kills) on a recent benefit album for survivors of the earthquake in Japan. But there are no other announced plans to release anything by any local bands. Whether a label like Polyvinyl has an obligation to release local music or work with local bands is certainly a point of debate. However, in a world where success is partially based on luck-of-the-draw, many music-lovers from around C-U (including this writer) would not mind seeing the label take a chance on more local bands.

Never Now

It’s pretty amazing how much technology has changed over the last fifteen years, and Polyvinyl has remained relevant by keeping up with what works for its artists. A fanzine with a 7″ in the back seems like such a quaint notion in today’s world of instant satisfaction. But as Matt explains it, technology has been very friendly to Polyvinyl and other independent artists.

Today if you hear about a band, you go to MySpace, Bandcamp, their website. It’s totally amazing how much more instantly you can disseminate information. Coming up totally through the emerging technology has been amazing to watch. It’s been a fun thing to be a part of, because of all the ways this has made the label grow and ultimately the bands grow.

We’ve been an artist-friendly label from the beginning, and every time we see something new our first thought is always how this can help our bands out. We’re pro new technology. We’re generally excited to see how it can help our bands.

Of course opportunities usually come with caveats and technology is no exception. Despite the success of sites like Bandcamp and Facebook, the last fifteen years have made it very easy to acquire music by illegal methods. While the major labels spent the early part of this decade suing their fans and working against new technology, labels like Polyvinyl have taken a very different approach.

Of course opportunities usually come with caveats and technology is no exception. Despite the success of sites like Bandcamp and Facebook, the last fifteen years have made it very easy to acquire music by illegal methods. While the major labels spent the early part of this decade suing their fans and working against new technology, labels like Polyvinyl have taken a very different approach.

I think our general sense, both the bands and the label, is that the more opportunities people have to hear your music, the better. Our primary goal is getting our bands heard, just like it always had been. In those ways, file sharing and bit torrents can have a really positive effect. I know there is a degree of diminished sales. It should come from a place where people who like the music should feel encouraged to support the bands, instead of stealing music. If you are using it as a discovery tool, I think it can be a good thing.

I feel like people who understand our artists are also of the same spirit where they are going into it with an intention of supporting the artist. They have an understanding that, if they really like something and they didn’t buy it, that band is losing out. We’ve tried really hard to get people to listen to our music ahead of time. Right now we’re doing everything we can to provide streams of our albums before they come out. If you want to hear a record, we are going to make it readily available.

And though the DIY world that Polyvinyl grew out of would have shunned any artist whose music showed up on a TV show or commercial, in a world where Minor Threat shows up on Entourage, things have definitely changed. Licensing is now seen by most as an opportunity for bands to get exposure and provide income streams that have been lost in the digital download era.

We approach licensing like everything else. We want to make sure any licensing is something our artists are comfortable with. Many of our artists are totally opposed to it, and we’re totally fine with that philosophy. But we have other artists who think it’s another great way to get exposure and get the word out about the band. I don’t think there is a wrong or right answer to that. We will go with whatever the band wants to do.

If I Don’t Work

With all the technology and social networks available to bands today, there’s still a question of why any band would even need a label. Radiohead famously eschewed record labels with In Rainbows, and many other established acts have sought to go without label support and use sites like Kickstarter to crowd fund and eventually release their albums. Some have found this model successful, though most, including Radiohead, have found their way back to record labels. As technology continues to move forward, it’s a question that will keep coming up for Lunsford and others running record labels — whether or not their time is running out.

From the start, we have tried to be as fluid about it as possible. Our job is to help our bands. It’s a very different baseline philosophy than a major label who see their job as to release songs and make money. Because we see our business as a place to help bands, we now have way more of a focus on different things. If that means we now have a couple of people whose entire job is to help bands manage the myriad social and technological outlets, that’s great because it ultimately helps the band communicate with their fans, but not at the expense of losing time they could be focusing on touring or writing songs. I think those sorts of things are what we’re doing more and more of as a record label. Because we see our job so much differently than traditional labels, we are able to be much more nimble about the sorts of things we spend our time doing.

I see this as the changing nature of record labels rather than the ‘death of record labels.’ I think we’ll continue to see the death of record labels whose philosophy it is to pump out CDs. The way things are changing, the cards are actually stacked in the favor of independently-owned, DIY type labels and bands. I think that it’s an amazing time to be doing this, even after fifteen years. It’s a much more favorable climate for our labels, even while the media narrative is that record labels are dying.

Made to Last Matt does not play an instrument and has never been in a band. I’m not certain if Darcie has a similar background, but she certainly has never been in a band of note. They are two fairly unassuming people who seemingly avoid the spotlight in favor of supporting others. This is probably why Polyvinyl remains somewhat of a C-U secret. But their impact on local, national and even international music is indisputable.

Matt does not play an instrument and has never been in a band. I’m not certain if Darcie has a similar background, but she certainly has never been in a band of note. They are two fairly unassuming people who seemingly avoid the spotlight in favor of supporting others. This is probably why Polyvinyl remains somewhat of a C-U secret. But their impact on local, national and even international music is indisputable.

Darcie and I dedicated ourselves to working as hard as possible for the bands. We got our feet wet with the zines and the DIY shows, but eventually we were trying to figure out how we could be involved and how we could help. The ultimate answer was that, of all the things we were doing, the record label was the one that stuck. And it made sense because it was the way we could get the music out by the bands in the most direct way.

And as the music world continues to evolve, Polyvinyl seems well-poised to move with it. It’s hard to say what record labels will look like in fifteen years, or if we will even call them record labels. But whatever model of music distribution and artist support is happening, you would be foolish to bet against Polyvinyl playing an important role.

—————————

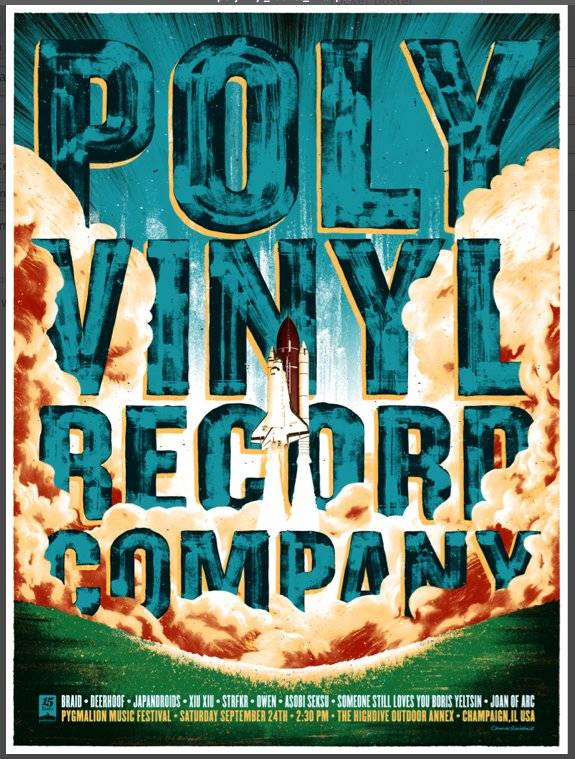

Polyvinyl Records will be celebrating their 15th Anniversary with an all day outdoor show at The Highdive on September 24th as part of Pygmalion 2011. More information and a full line-up is available here.

Braid photo by Rachael Dietkus-Miller

2008 Polyvinyl “family” photo by Justine Bursoni

Headlights photo by Grady Highberry