They have brown hair, or blonde, or perhaps something in-between. Their eyes are the average shades and colors that a human would have; their skin being the same as well. They go to school, earn degrees, go to work, sleep, and eat. They go to the movies and possibly frequent bookstores, have religious services and pray.

This is what a pagan looks like and what they might do during an average day. They are the same as any other human on this planet with faith. However, instead of praying to perhaps one God, they pray to a goddess, god, a group, or none of the above. They are neither distant beings of myth, nor are they satanic, and they don’t perform human sacrifices.

In fact, there are pagans in Champaign-Urbana.

This isn’t a recent phenomenon though. The community has been here for years. During the ‘80s and ‘90s, the known community began to swell from a couple of dozen people to over a hundred.

“In the Champaign-Urbana area, there are probably a few hundred pagans, mostly all solitary,” said Ian Phanes*, an Urbana pagan who has been part of the community since the late ‘80s. “I don’t know all of them, and there are some involved in groups that many don’t know about.”

The U.S. Census doesn’t keep records for religious affiliation, meaning that official numbers are difficult to obtain. Yet, according to the 2008 American Religious Identification Survey — the largest national survey on American religion — the number of people who responded as being pagan was 340,000. In the 2001 survey, that number was 140,000, meaning that the number had more than doubled. However, scholars are wary of trusting those numbers as proof of a fast growing population.

The U.S. Census doesn’t keep records for religious affiliation, meaning that official numbers are difficult to obtain. Yet, according to the 2008 American Religious Identification Survey — the largest national survey on American religion — the number of people who responded as being pagan was 340,000. In the 2001 survey, that number was 140,000, meaning that the number had more than doubled. However, scholars are wary of trusting those numbers as proof of a fast growing population.

Given all of the stories and stereotypes regarding pagans, what is often lost in translation for this group of people is who they are exactly, and what they do. What exactly is a pagan, and what does that entail?

Being “pagan” isn’t really a set or defined concept. There are various answers depending on which source is consulted, making the definition of paganism an elusive one.

The term pagan has two definitions. The first states that a pagan is a “Heathen, especially a follower of a polytheistic religion (as in ancient Rome).” The second states that a pagan is, “one who has little or no religion and who delights in sensual pleasures and material goods: an irreligious or hedonistic person” (Merriam-Webster).

The New Encyclopedia of the Occult has a completely different and longer definition, one that takes up five pages in fact. The first part of the definition states:

[A] general term for the traditional polytheistic religious traditions of Europe and the Mediterranean basin … later applied to all religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, and has also been borrowed by many groups and people in the modern Neopagan revival, some of which claim connections to ancient Paganism.

Perhaps the most diverse responses come from those who practice paganism themselves. Not everyone agrees with the textbook definition, and some argue as to whether there really is a textbook definition at all. “It can’t be defined, but it can be described,” said Phanes. “It can be a range of things including polytheism, but it’s not mandatory. There is also a nature focus,” he added:

People are getting connected by all these different groups and relationships. It’s a movement. Even if it’s not, everyone knows each other. If you do the seven degrees of paganism, you are probably connected to everyone. It’s sort of what makes paganism a thing. Some are very well defined traditions, like Asatru and Gardnarian. How they connect varies.

Asatru is a Germanic and Norse pagan religion that follows ancient worship of Germanic deities. Gardnarian, however, is a specific tradition within Wicca, of which there are many. It was founded in Britain by Gerald Gardner in the early 1950s.

Phanes continued to explain that paganism is similar to that of a pot of boiled spaghetti, in that it is all connected to each other with everything overlapping at some point. Ideas from one group and tradition can be incorporated into another group.

Catherine Novak, owner of Beads N Botanicals, believes that the definition is at the base of the word’s roots. “You use the term pagan for a real catchall category,” she said. “Technically, you get pagan, and then you get heathen. Heathen is of the heath and pagan is of the country. So, country folk, if you go back to the origins.”

“The word pagan means ‘not a Christian,’” said Kent Shanholtzer, an Urbana shaman. “It means unsaved, unredeemed, heathen. Heathens have never heard the word of Christ, and are not blamed for it,” he said. “Pagans have heard of it. By definition, anyone who’s heard of the gospel or had it said to him, but has not accepted it, is considered a pagan.”

Alyssa King*, a Champaign eclectic witch (one who draws from multiple different paths and practices), explained that the term is extremely diverse and large, and it cannot be defined as just one thing, but instead covers a broad topic of items. On the other hand, Joshy Davis*, a Champaign pagan, agreed with the definition given by The Encyclopedia of the Occult.

“Not everyone agrees on definitions,” said Phanes. “For example, some people who say that they are Wiccan aren’t practicing what I would call Wicca. My term is more narrow; I like to be more specific. It’s a huge category, so let’s name the pieces of the category. Say that two people are using word ‘A’ for what I would call ‘X’ and ‘Y.’ It’s linguistic.”

Wicca is perhaps the most popular and widely known religion in paganism. While there are numerous traditions, most follow a similar philosophy that there are two deities, one female and the other male, known simply as The Lord and Lady. These can take on the aspects or image of any female and male deity, such as Isis and Osiris, or Athena and Aries.

Wicca is perhaps the most popular and widely known religion in paganism. While there are numerous traditions, most follow a similar philosophy that there are two deities, one female and the other male, known simply as The Lord and Lady. These can take on the aspects or image of any female and male deity, such as Isis and Osiris, or Athena and Aries.

Definitions aside, all who are pagan can agree that they felt called to their own particular path in some way, shape, or form. When and where this happens is obviously personal to each person, much like any religious calling. One reason is what Phanes touched on earlier: paganism offers the opportunity for solitary practice. As Alyssa King explains, “I practice solitary. I am in paganism so I don’t have to deal with the middleman, so I don’t have to deal with the High Priest and Priestess. I’m not into it.”

The second reason focuses on how witchcraft and paganism are depicted in the media, with the image of “personal empowerment and an inherent glamour” now evident more than the stereotypical evil witch with warts covering her face. “It was more of like a calling, it just felt like something I was supposed to do,” said King. “I grew up a Southern Baptist. I wasn’t really feeling Christianity, and then paganism kind of just came along.”

“There was freedom, the freedom to do pretty much what you wanted, choose your gods, and select your doctrine,” she explained. “There’s no middleman and no judgment from other pagans that I’ve come across. If you feel a connection with a god or goddess, it is basically whatever you choose.”

Joshy Davis joined the path after being a Christian all his life. He began researching paganism at the age of 12 after watching the television show Charmed. He made his decision when he was 13 after facing a personal crisis with his faith:

At the time, I was very confused about my feelings, because I knew I was attracted to males, but thought I could also be attracted to females. I went to Church and the lesson that day was Sodom and Gomorrah, which led to the discussion that how the bible is interpreted, being sexually attracted to the same sex is wrong.

That night I prayed to God as I was used to and told him that I’m sorry, but I couldn’t understand how it was wrong, and I told him that I would respect and love what I learned, but I just didn’t feel right being a Christian anymore. I cried that night, and from there I decided to pursue Wicca as my religion.

As it did with Davis, modern media may have had an influence in introducing the concept of magic and paganism to the overall populace. Popular films such as Harry Potter, The Covenant, and Twilight romanticize the occult.

Another reason for the explosion of interest in paganism is due to the Internet. Because rituals and practices vary greatly between one pagan to the next, there really isn’t a correct way to practice. Consequently, some go beyond the traditional boundaries of physically performing rituals and praying. These individuals occasionally practice in cyberspace. Two popular and informative websites include The Witches’ Voice, a Neopagan news and networking site and Pagan Space, a social networking site for pagans and others of the occult community.

Thus, unlike many organized religions, paganism doesn’t necessarily require a specific type of space or list of guidelines for how to properly practice. And since many do so individually, they are able to choose the best route for them to pursue, both in manner of prayer and worship. With so many diverse routes in paganism, various worshipping practices emerge for each group. This also means that people are able to create their own paths of paganism such as new traditions or, for lack of a better word, denominations.

“My practice is similar to Wicca in that I do rituals and I do circle work,” said King. “These are things that I adhere to. However, there are some things that I have noticed in Wicca that don’t apply to me at all, like Gardnerian Wicca. In that, there are different degrees [for hierarchy] and initiations to do, and I don’t follow it.”

Many would also consider Shanholtzer a pagan since he is a shaman. Shamanism is often tied to animism, or the concept that spirits reside in things besides just humans such as animals, trees, the earth, etc. It is also traditionally known to be tied to Native American religions of the  Americas. However, Shanholtzer isn’t Native American. His ancestors are known as the Sami, a group of indigenous people who live near the arctic near Sweden. To them, a shaman is a nature holy man and even a scientist.

Americas. However, Shanholtzer isn’t Native American. His ancestors are known as the Sami, a group of indigenous people who live near the arctic near Sweden. To them, a shaman is a nature holy man and even a scientist.

“It’s a catchall term for nature science magician,” said Shanholtzer. “We are the finders of food, track the stars, and possibly built Stonehenge. Among my mother’s people, I am known as a noaidi.”

“The details of the religion are lost though, because they’re gone,” he

added. “The shamans were burned or they fled to America. The exact traditions are dead, but some of the decedents are trying to make some identity.”

One of these practices is called joiking or yoiking, Sami singing. Shanholtzer described it as being similar to skat in jazz music: it is mostly improvisational. Joiking are songs and chants than can be utilized to will something to occur. This can be as simple as wishing for it to stop raining or for snow to finally start falling.

As another part of his practice, Shanholtzer takes on different totems or animals at various times throughout the year. These can change from season to season. Taking on totems allows the person the ability to take on qualities of the totems in question:

You’re allowed to embrace another archetype other than your birth totem. At times, you can go so deep into a totem that you are it, and you can take on the aspects of the totem or the animal. Sometimes it surprises you. If you are really connected to your totem, you can discover things from the universe about the totem that you couldn’t learn with your senses.

Shanholtzer claimed that while on the path of the stag last year, he was able to lie down on the ground and sleep with deer in Busey Woods. “Shamanism is about living,” he continued. “It’s not separate from life. It is life.”

As a shaman, Shanholtzer doesn’t worship multiple gods and explained that he practices low magic (or, country magic). In this, no tools are needed except for yourself. Low magic’s partner, high magic (or, ceremonial magic), is usually practiced by those who utilize ritual and possibly ceremonial items, such as an athame, a ceremonial dagger.

An example of ceremonial magic is Wicca. In this religion, circles are cast by calling the four directions and their corresponding elements. East is wind, south is fire, west is water, and north is earth. While in this circle, the ground is considered sacred and rituals are able to take place.

Though Shanholtzer does not practice in this way, Davis and King can be considered practitioners of ceremonial magic. Wicca often influences Davis’ practice, although he wouldn’t necessarily define himself as Wiccan:

I usually define myself as pagan or as a witch, because I don’t have a set path. I practice a lot of stuff that is based on Wicca, such as the magical and religious structure and the holidays, but I also practice a lot of stuff that is not Wicca.

I’ve been influenced a lot by Wicca, and to a point I guess you could call me an Eclectic Wiccan, but I have never been inducted into a linage of Wicca, and never studied under an initiate. Depending on which pagan social circles you interact with, you cannot claim to be Wiccan without doing so. However that is a matter of debate.

It’s obvious that paganism is difficult to define and its concepts are extremely diverse. Most of what non pagans know about the occult now comes from the popular media and television shows such as the Secret Circle, True Blood, Supernatural, and Charmed. Yet even with so many people now saturated with information on the occult, some of it legitimate and some not, many pagans still refuse to “come out of the broom closet” out of fear of discrimination.

King decided to become pagan while she was in high school. She attempted to hide it from her family, but she was eventually discovered. “That went down like a lead balloon,” she said:

My stepfather found my Book of Shadows. When that got found, I actually got knocked out. He burned it. I was about 17, really close to 18. I bided my time until I went to college and then I did my own thing. It was more about me being patient. You pick your battles.

Even though she is now on her own, she still hides her Book of Shadows (a personal book of spells and writings), along with all of her other pagan items, in her closet.

When he was younger, Davis said that he also experienced his own share of discrimination. In high school, a few of his classmates told him that he was going to go to hell for being a pagan and for practicing witchcraft. This didn’t faze him, though. Instead, he was more concerned about his family finding out:

I, at first, hid it because my nuclear family, while not overly religious … my mom at the time classified herself as a Christian, and still does. And most of my blood-related family were more churchgoing folk, but my stepfather and his family [were] more fluid in their spiritual beliefs.

My aunt and uncle came home and were going to spend the night in my room while I was away visiting my Dad. At the time I had a very simple altar that consisted of five incense sticks connecting five tea lights to a pentagram. Before I left for my dad’s, I picked up the sticks, and come Christmas day, while we were opening up presents, my aunt asked me if I had any more objects on my altar other than the five candles, I had forgotten to put the candles in a different position.

Davis’ fears were abated though; his family didn’t say anything about it. He now considers it unnecessary to hide his faith from them.

According to Phanes, it is commone for many pagans to not come out publicly:

There are probably lots of different reasons for not being public. For some people, it’s a professional issue. The woman who initiated me into Blue Triscol Wicca — I can say this now — was a doctor. I still know professionals in the community who are still in the broom closet. It could truly be professional suicide for people who are known publicly to become known as pagans. They wouldn’t be taken seriously, and religious pressure would form around them.

Phanes’ former religious leaders once told him that they were accused of being Satanists while in the south. The two had a sun catcher with the image of a cat, and another with leaves. People claimed that the shed in their yard was a satanic temple. Ironically enough, no one realized that the two were actually pagan.

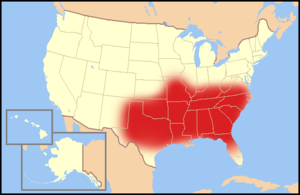

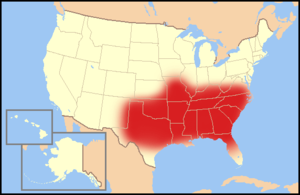

Even though Champaign-Urbana is on the edge of the bible belt, a stereotypically Christian area spanning from western Texas to the east coast, and from southern Illinois to the U.S. border (map, right), pagans here do have reason to be concerned and overly cautious. In 2003, Witch School opened in the Hoopeston-Rossville area of Illinois, an hour away from Champaign. For six years, those at Witch School faced hostility from their neighbors in the area, including the Christian churches. According to one article in the Chicago Tribune, residents of the town would often protest the school and pray for the pagans to leave. Some even went as far as sprinkling the wheels of their cars with holy water and driving around town in an attempt to make them leave.

Even though Champaign-Urbana is on the edge of the bible belt, a stereotypically Christian area spanning from western Texas to the east coast, and from southern Illinois to the U.S. border (map, right), pagans here do have reason to be concerned and overly cautious. In 2003, Witch School opened in the Hoopeston-Rossville area of Illinois, an hour away from Champaign. For six years, those at Witch School faced hostility from their neighbors in the area, including the Christian churches. According to one article in the Chicago Tribune, residents of the town would often protest the school and pray for the pagans to leave. Some even went as far as sprinkling the wheels of their cars with holy water and driving around town in an attempt to make them leave.

In 2009, Witch School vacated the area and set up shop in Salem, Massachusetts. Even though members said that the reason for this was due to insufficient internet service at their current location (Witch School is predominately a pagan website), the discrimination was still evident. Even though this was an extreme situation, the threat of such discrimination still worries some.

Because a large number of Christians are not open-minded about paganism, Phanes advises those who may be considering coming out of the broom closet to their friends and family to think about the range of responses that they could receive. The important question is whether or not they can handle those responses, whatever they may be.

However, he knows that in the future, numbers will continue to grow and people will be made more aware of what paganism really is. His biggest hope is that the community of pagans in Champaign-Urbana will continue to grow and prosper:

This is a university town. Paganism is still largely a young people’s movement. The word ‘stable’ doesn’t really describe it. Maybe 50 to 100 years from now, when it is a multi-generational thing, a good number of pagans will have grown up in paganism. Stagnation is a bad thing. I’m much more interested in a healthy community.

~~*~~

*Names have been changed.

~~*~~

Pagans in C-U, part 2

Pagans in C-U, part 3

~~*~~

Articles in this series contain excerpts from Laws’ masters thesis, earned at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.