is for piano. The instrument. And if it hasn’t yet occurred to you, I’m here to tell you that this is serious stuff in Champaign-Urbana. For jazz or classical and most every other tune, the piano can give the most versatile delivery. In one grand swoop it offers 88 tones over 7 octaves plus a minor third; loud or soft; staccato or sustained, solo or accompaniment. There’s a lot of joy built in. The next time you walk by the old Robeson’s Department Store building at the corner of Church and Randolph overlooking Westside Park, give yourself a moment to imagine a piano letting loose from that rooftop for the Saturday night dances they held in the 30s and 40s. Somehow, someone hauled a piano up there each week for dancing under the stars. Wouldn’t that be an experience to bring back to downtown nightlife?

is for piano. The instrument. And if it hasn’t yet occurred to you, I’m here to tell you that this is serious stuff in Champaign-Urbana. For jazz or classical and most every other tune, the piano can give the most versatile delivery. In one grand swoop it offers 88 tones over 7 octaves plus a minor third; loud or soft; staccato or sustained, solo or accompaniment. There’s a lot of joy built in. The next time you walk by the old Robeson’s Department Store building at the corner of Church and Randolph overlooking Westside Park, give yourself a moment to imagine a piano letting loose from that rooftop for the Saturday night dances they held in the 30s and 40s. Somehow, someone hauled a piano up there each week for dancing under the stars. Wouldn’t that be an experience to bring back to downtown nightlife?

The eminent official history of the piano as we know it begins around 1700 in the court of the Medici family in Padua, Italy. In their employ was Bartolomeo Cristofori, who transformed the keyboard beyond the harpsichord to the potential of the modern instrument. He dreamed up the action of the hammers striking rather than plucking the strings, and then releasing so that the sound can be sustained. And with these innovations, the output was loud or soft depending on the way the key was struck; and so it was a piano-forte, Italian for soft-loud.

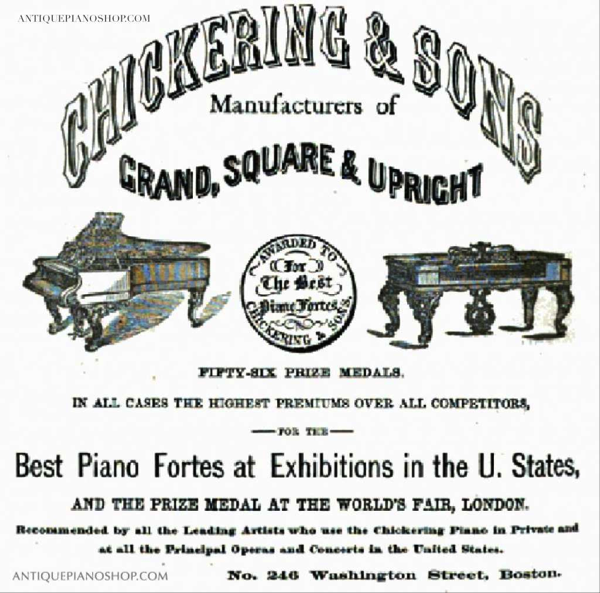

It took American inventiveness to make the piano an obtainable instrument, more easily made, with the innovation of the cast-iron frame. The popularity of great American ragtime, jazz, bebop and beyond, uniquely a legacy of the genius of African-American musical cultures, gave this side of the Atlantic a definite edge in expressiveness and art. Chickering was the first piano manufacturer on this side of the Atlantic, open for business in Boston and then New York from 1823, and the floodgates opened after that.

By 1869, 35,000 new American pianos were made each year, up to 350,000 in 1910. Champaign had its own piano maker, William A. Johnson Co., which operated for some years after 1907 in the old Herff + Jones Cap and Gown building. And around this time player pianos hit the market and became wildly popular.

All this made the piano a coveted instrument to have at home. Keyboard instruction was introduced in 1872 at the Illinois Industrial University, six years later re-named the U of I, and its School of Music, established in 1897, encouraged a scene where all kinds of music flourished.

Pianos proliferated. There are some 220 instruments at the U of I today between the School of Music and the six Steinway concert grands at Smith and Krannert Center. And there is the occasional off-campus adjunct, like the Baldwin grand at The Iron Post in Urbana that was contributed by some faculty so their jazz students could have real-life gigs to satisfy the requirements of a graduate degree.

The man who knows these instruments intimately is the official piano technician of the School of Music and Krannert Center, John Minor. He makes the rounds from practice rooms to concert stage hour by hour as needed. For one performance at KCPA a piano may require 3 tunings to be at ideal adjustment. Every visiting pianist fills out an information sheet with their requirements and preferences. Minor likes to give them a choice between the Steinways – the German Hamburgs, one old and one brand new, and the New York-made, which do have noticeably different characters. The pre-performance preparation can be rigorous, for challenging specs submitted by individual performers. George Winston, who describes himself as a “rural folk pianist” and often plays in his stocking feet and flannel shirt, requires sophisticated technical support for the best action from the particular keys he’ll rely on repeatedly.

John Minor fine-tunes Krannert’s new Hamburg Steinway

Like many people who find a true calling that keeps them dedicated day in and day out, 7 days a week if necessary, Minor fell into this work by instinct. He began studying vocal music and education in the 70s in Sioux City but found that a bit esoteric and longed for a more hands-on involvement. He found the right niche at Western Iowa Tech, and was certified by the Piano Technician’s Guild through their demanding written and performance testing; but he says that training is only an introduction to the skills required to be a concert technician.

I was delighted to accompany Minor as he touched up the Hamburg Steinway for the recent performance of the Haifa Orchestra in Foellinger Great Hall. And sure enough he was at the concert that night to appreciate the results of his work. Some pianists require that a technician be available during intermission in case there are issues to be adjusted on the fly.

The highlight of Minor’s career – so far – came last June when he luxuriated for a full day in the Steinway factory in Hamburg, Germany, selecting a new 9-foot concert grand for Krannert Center. Steinways are built in both New York and Germany, with significant differences in parts and character. The German instruments carry a certain mystique and are considered by some superior for craftsmanship and performance. Their materials are unique, and their hammers made with a different technique. KCPA had won a grant that demonstrated the need for this new superb instrument, in the vicinity of $190,000 including transatlantic shipping. Minor sampled the six pianos in the shop and chose the one he found most satisfying. Treat yourself to its magnificence and take in a performance at Foellinger Great Hall, which itself is an outstanding recording studio, used specifically for that by luminaries including the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and the Sydney Symphony.

There’s a lot to admire in what Minor does to prepare a Steinway for a performance. The piano is the centerpiece of the orchestra; every other instrument tunes to it. The critical note is the A above middle C, known as the Concert A. In America and England this is traditionally tuned to A440, measured in herz, or cycles per second, the standard unit of frequency. In continental Europe however the preference is for A442, and Minor may be required to increase the piano strings’ tension to this, resulting in a “sharper” sound. Technicians are trained to tune by ear and tuning fork, but now often also refer to the Reyburn CyberTuner, available for your own trusty ipod, iphone or ipad. However, tuning is a subjective art, and the best technicians make their final adjustments according to the ultimate judge, the human ear.

A piano is a big investment, for a home or for a school. Universities are one of the largest markets, and there is fierce competition from makers for them to have only one particular brand, more often than not the eminent Steinway. Yamaha puts in a good showing, partly because they frequently “loan” pianos to schools at no cost for practice use, and then sell them later on campus. Be aware of this if you are tempted to purchase a “U of I-owned piano” at the spring sale.

A long-time trusted supplier in town is Piano People, founded in 1979 and masterminded by Steve Schmidt. As he told me, pianos don’t improve with age; and so the bulk of their business is in restoration and rebuilding. A fine Steinway may need to be rebuilt every 50 years, and that is Piano People’s specialty. They are known for their work as far away as Rice University in Texas and by clients in New York and Colorado.

Steve Schmidt of Piano People

Schmidt originally came to Champaign Urbana as a working musician, in 1973, playing keyboards with the band Ginger. The story is that the local rock scene in the 60s and 70s was amazingly rich, surpassed by only Nashville and Austin. His band dissolved after about five years and Schmidt needed to find another way to make a living. He started reading books about pianos and got interested, so he bought eight to ten old uprights and started taking them apart. At over 250 pounds for an upright and a minimum of 500 for a grand, this wasn’t a business that could be accommodated at home, so he moved to a storefront next to the original Italian Patio restaurant. In 1979 he formed Piano People with two other experienced tuners and has been busy ever since.

Schmidt, who specializes in piano “action,” says the most important aspect of a piano to the expert performer is how fast and evenly the keys respond. The touch is in the weight of the keys, commonly 50 grams. Specific performers go to great lengths for the lightest, most responsive touch. The Canadian legend Glen Gould searched all his life for the perfect piano, and was elated to come upon his dream, one Steinway 319, which was then tragically dropped off a loading dock. For serious piano people, that is a story you may enjoy.

Schmidt has learned mostly on the job and from other technicians. He had the opportunity some years back to meet Franz Mohr, on tour after the death of legendary Russian pianist Vladimir Horowitz, with the master’s Steinway. Mohr’s father and grandfather were artisans at Steinway before him and followed the custom of signing their names to parts inside the pianos they worked on; Schmidt has come across them a number of times. Mohr shared the story of how he adjusted the weight of the keys extremely light to suit Horowitz’s touch by replacing the hammers in the New York grand with German counterparts, which are wider and give more leverage. Steinway has long gone to extreme lengths to satisfy its prize performers; they call their pianos “the instrument of the immortals.”

Today, piano manufacture and sales have dropped precipitously. According to Schmidt 99% of today’s new pianos are built in Asia. Yamaha, which started building upright pianos in Japan in 1900, is the giant. John Minor acknowledges that Yamahas are built extremely uniformly, and offer a brilliant sound that’s good for jazz; Schmidt considers it “brittle.” But most discerning ears find Steinways superior in range of expression and the subjective qualities of warmth and beauty. And there is fierce competition from the digital keyboard industry, which now sells three times the number of pianos. In a sober moment, Schmidt will say that piano-making is a dying industry, but who’s to know?

For those of us in love with the genuine 88-note, 220-string piano, the acoustic instrument offers a unique relationship. The vibration of physical strings moves through the body of the player and throughout the physical space of the surrounding room. A high quality keyboard can produce sounds sampled from the best concert grand in the best performance hall in the world, but it can never match the visceral experience of the real thing.

Treat yourself to some of the piano magnificence in this community.

And while you’re at it, you can savor the origins of another item in the endangered category: a genuine Lombardic handlettered P, as shown in the initial photograph above, with the master hands of Rachel Jensen, beloved local teacher and accompanist. The roots of our form of P developed out of the Phoenician shape that represented the sound “p”, meaning mouth. The Greeks kept the name pi but changed the form to what we know as the mathematical symbol. The Romans went back to the Etruscan shape, turned it around, and P assumed its place as the 16th letter in the Roman alphabet.

Phoenician “pe”

Greek “pi”

Etruscan “p”

Cope Cumpston is a typographer, book designer, and community enthusiast resident in Urbana. You can reach her here: cope.c@comcast.net

The archive of abecedarian C-U lives here: